By Arlo Blaisus (PDF Version)

I. Introduction

The United States is one of the only developed democracies in the world that places the responsibility of maintaining voter registration on its citizens.[1] This policy contributes to the U.S. having lower levels of democratic participation than many other democracies,[2] reducing the effectiveness and legitimacy of U.S. governmental institutions.[3] U.S. voter registration rates are also depressed due to its history of voter registration laws, which developed as an intentional means of disenfranchising minority and low-income citizens.[4] To address these problems, Congress passed the National Voting Rights Act of 1993 (NVRA) with the intention of “maximizing opportunities for voter registration.”[5]

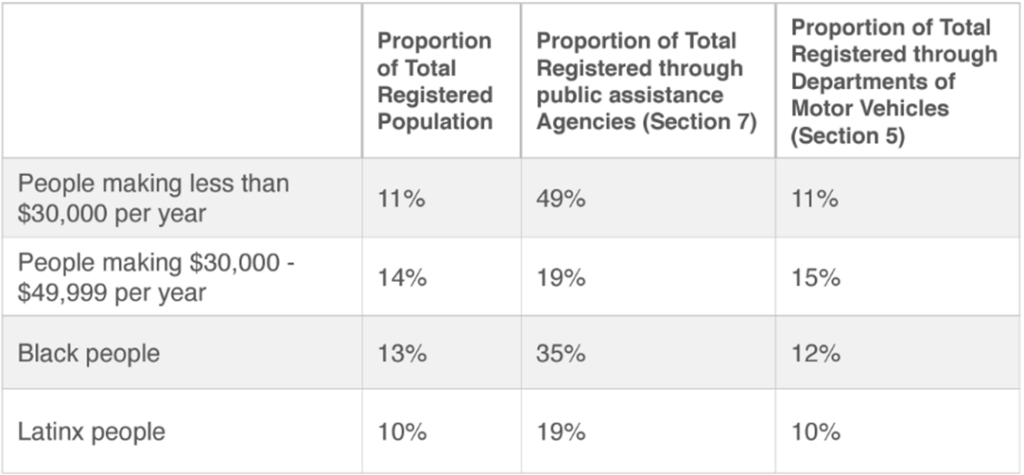

The NVRA created national standards for voter registration laws and facilitated the registration of millions of additional voters.[6] The NVRA is commonly known as the Motor-Voter Law because it combined voter registration with driver’s license applications.[7] Section 7 of the NVRA requires state governments to provide voter registration services at public assistance offices.[8] Congress added this section out of concern that the Motor-Voter provision of the law would be ineffective at registering eligible citizens with lower incomes or from racial minorities.[9] Section 7 has proved to be a very effective solution to this concern; an analysis of 2016 census data found that 49% of citizens making less than $30,000 per year and 35% of Black citizens registered to vote through public assistance agencies.[10]

However, voter registration rates and overall democratic participation in the U.S. still lag behind other developed democracies.[11] In 2020, over 27% of the U.S. citizen voting-age population — more than 63 million citizens — were not registered to vote.[12] Further, low-income and minority citizens continue to register at below-average rates.[13] The low voter registration rate in the U.S. presents a significant barrier to democratic participation.[14] In 2016, only 55% of the U.S. voting-age population voted, placing the U.S. thirty-second worldwide for voter turnout rates.[15]

State governments’ resistance to vigorous implementation of the NVRA is a significant cause of the United States’ low voter registration rates.[16] One way this resistance manifests is through States’ narrow interpretations of NVRA Section 7.[17] This section requires that “[e]ach State shall designate as voter registration agencies . . . all offices in the State that provide public assistance.”[18] Despite this broad language, States generally include only a limited number of public assistance agencies in their Section 7 agency programs.[19] Notably, no State has designated Public Housing Authorities (PHAs) as Voter Registration Agencies (VRAs),[20] even though PHAs are state agencies that administer public housing assistance.[21]

This paper proposes that the NVRA requires States to designate all PHAs that administer programs funded by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) as VRAs. Applying Section 7 to PHAs would effectively increase the U.S.’s low rates of democratic participation.[22] It would also further Congress’ express purpose in passing the NVRA to “establish procedures that will increase the number of eligible citizens who register to vote.”[23]

This paper proceeds in several sections. First, it explores the current legal structure of voter registration laws established by the NVRA and how discriminatory State voter registration practices influenced the creation of that structure.[24] Second, this paper shows that additional enforcement is necessary to overcome State resistance to implementing the NVRA and achieve Congress’ intent of increasing the number and diversity of registered voters.[25] Third, this paper demonstrates that PHAs meet the requirements of the VRA provision of NVRA Section 7.[26] Therefore, States are out of compliance with federal law for failing to designate PHAs as VRAs.[27] This paper concludes that designating PHAs as VRAs would help achieve the purposes of the NVRA by increasing voter registration rates and enhancing democratic participation.[28]

II. Voting Registration Laws in the United States

The United States is unique among advanced democracies in requiring personal voter registration that places the onus on voters to maintain their eligibility.[29] Registered voters represent a much smaller share of potential voters in the U.S. than in many other countries, primarily due to voter registration being an individual’s responsibility and the decentralized nature of State voter registration laws.[30] The low rate of voter registration in the U.S. is not an accident. A primary motivating factor in the development of voter registration laws in the U.S. has been the purposeful disenfranchisement of voters to consolidate political power.[31]

This history shapes the current legal structure of voter registration in two critical ways. First, the modern national structure of voting registration law was created by the Voting Rights Act of 1965[32] and the National Voter Registration Act of 1993.[33] Congress intended both laws to correct overly restrictive State voting registration laws.[34] Second, despite the improvements made by these laws, the poor, uneducated, and minority citizens historically marginalized by voter registration laws continue to register to vote at below-average rates.[35]

A. Historical Development of U.S. Voter Registration Laws

Before the late nineteenth century, there were no state or federal requirements for white men to register to vote in the United States.[36] State only began adopting voter registration laws following the Civil War as a part of Jim Crow in the South and as a backlash to increasing immigration rates.[37] In the South, voter registration laws were a direct response by White property owners to the passage of the 15th Amendment, which gave formerly enslaved people the right to vote.[38] These laws effectively reestablished race-based restrictions on voting by purposefully excluding newly enfranchised Black voters.[39] In Northern and Western states, voter registration laws disenfranchised immigrants and migrant workers.[40] The movements to pass voter registration laws in both regions were “elitist, reactive to the threat of political insurgency, and apparently calculated to achieve political stabilization while restoring control by strongly conservative interests.”[41]

Typical of Southern states, Louisiana enacted harsh new voting registration requirements in 1898 that included literacy qualifications and property-owning requirements. [42] However, under the infamous “Grandfather Clause,” the new restrictions did not apply to anyone with a father or grandfather entitled to vote before 1867.[43] This clause precisely targeted Black voters with new restrictions while protecting the voting rights of the White political class.

Louisiana passed these laws during a State Constitutional Convention which was called explicitly to “establish the supremacy of the white race”[44] by disenfranchising the “mass of corrupt and illiterate voters.”[45] The convention had its intended effect; by 1900, the percentage of African Americans registered to vote in Louisiana plummeted from 85.2% to 4%.[46] Alabama’s strict Jim Crow voter registration laws were similarly effective, with just 1% of eligible African Americans in the state registering to vote in 1902, compared with 75% of Whites.[47]

In Northern States, early proponents of voter registration laws claimed to be concerned about voter fraud and the corrupting influences of urban political machines.[48] However, the fiercely partisan political battles of early Northern voter registration laws generally pitted urban working class and immigrant voters against nativist elites.[49] The racist and xenophobic intent behind voter registration laws was not as blatant as in the Jim Crow South. However, it clearly motivated activists such as magazine editor George Gunton, who wrote about the “evil of ignorant voting” and complained that “too many of our foreign-born citizens vote ignorantly.”[50] Further, there was little evidence of the fraudulent voter registration that purportedly justified voter registration laws.[51] Documented voting fraud at the time almost always involved organized efforts by election officials, not voters. [52] Thus, the voter registration laws sought by activists would not have prevented the proven cases of voter fraud.[53]

Despite the clear discriminatory intent of many voter registration laws,[54] state courts mostly upheld these laws throughout the first half of the twentieth century.[55] On rare occasions when federal courts struck down discriminatory voter registration laws, States would switch to different methods to reach the same result.[56] For example, when the U.S. Supreme Court declared Oklahoma’s Grandfather Clause unconstitutional in 1915, Southern States switched to a system of “Whites Only” primary elections to keep Black voters marginalized.[57]

Civil rights legislation, starting in the 1960s, began to establish national standards for voter registration.[58] Before 1965, African Americans registered to vote at a nationwide average of 29%, compared to 73% for Whites.[59] The Civil Rights Act of 1964[60] and Voting Rights Act of 1965[61] curbed the worst abuses of voter registration laws and led to over 60% of eligible Black voters being registered by 1986.[62] However, there remained a “plethora of byzantine and ambiguous state registration procedures” that “often denied voters the chance to register with ease and convenience.”[63] Further, voter registration rates plateaued, and democratic participation rates decreased nationwide in the wake of the Watergate era.[64] Pressure started building in the Democratic Party for a strong national voter registration law, which, after many failed attempts, resulted in the passage of the National Voter Registration Act of 1993.[65]

B. Legal Structure of the NVRA and Section 7

In passing the NVRA, Congress declared that citizens have a “fundamental right” to vote and established a “duty of the Federal, State, and local governments to promote the exercise of that right.”[66] Further, Congress stated that discriminatory voter registration laws have a “direct and damaging effect on voter participation” and “disproportionately harm voter participation by various groups, including racial minorities.”[67] These findings demonstrate that Congress was fully aware of the discriminatory history of State voter registration laws and intended to correct the abuses of those laws.

Congress’ primary purpose in passing the NVRA was to “establish procedures that will increase the number of eligible citizens who register to vote.”[68] To implement this purpose, the NVRA directs States to provide voter registration services to driver’s license applicants at State Departments of Motor Vehicles[69] and requires States to accept standardized mail voter registration forms created by the Federal Election Commission.[70]

However, the drafters of the NVRA were concerned that these measures would be ineffective at registering voters who did not have driver’s licenses, in particular, citizens with lower incomes or disabilities.[71] Congress included Section 7 to address these concerns by requiring States to designate certain state governmental offices as VRAs.[72] This requirement, known as the Agency System, is the subject of this paper.

Section 7 requires States to designate as VRAs “all offices in the State that provide public assistance” or are “primarily engaged in providing services to persons with disabilities.”[73] These are known as Mandatory VRAs.[74] Section 7 also requires States to designate at least some other offices, such as public libraries, public schools, and offices of city and county clerks, as VRAs.[75] These are known as Discretionary VRAs.[76]

Section 7 VRAs must distribute mail voter registration forms, assist applicants in completing voter registration forms, and collect and transmit completed voter registration forms to state election officials.[77] Further, VRAs that are public assistance agencies must distribute mail voter registration forms with each application for service or assistance and with each recertification, renewal, or change of address.[78] To enforce these provisions, the U.S. Attorney General and private citizens may bring civil actions for declaratory or injunctive relief.[79]

C. Effects of the NVRA and Section 7

The NVRA quickly succeeded in raising the national rate of voter registration.[80] As a direct result of the new law, an additional 27.5 million citizens registered to vote.[81] Within two years of the law taking effect, 73% of the voting-age population was registered to vote, the highest percentage since accurate statistics started being recorded in 1960.[82]

Section 7 also successfully increased the electorate’s diversity by registering low-income and minority individuals.[83] Confirming the concerns of the drafters of the NVRA, only 11% of people making less than $30,000 per year and only 12% of Black individuals registered to vote at State Departments of Motor Vehicles in 2016.[84] However, 49% of citizens earning less than $30,000 per year, and 35% of Black citizens, registered to vote through public assistance agencies under Section 7 in 2016.[85] These statistics demonstrate the value of Section 7 in correcting the historically discriminatory impact of State voter registration laws and show the prescience of the NVRA’s drafters in recognizing that Section 7 was necessary to

maximize opportunities for citizens to register to vote.

Despite the successes of the NVRA, the law has failed to bring the United States in line with the voter registration rates of other advanced democracies. In 2016, only 64% of the U.S. voting-age population was registered to vote, with only 56% casting a ballot. Low-income individuals continue to register at lower rates than higher-income individuals.Citizens from racial minorities continue to be underrepresented among registered voters, while White individuals continue to be over-represented.<a “=”” href=”https://sites.temple.edu/pcrs/?p=574&elementor-preview=574&ver=1699288117#_ftn89″>[89]

Further, research indicates that there continue to be significant barriers preventing citizens from registering to vote. A Census Bureau study in 2020 found that almost 15% of eligible non-voters wanted to register, but State registration deadlines or lack of knowledge about voter registration procedures stopped them from successfully registering.[90] Given that over 63 million voting-age citizens in the U.S. are not registered, this study indicates that almost 10 million eligible citizens wanted to register to vote but were unable to do so.[91] Further, a Pew Research poll found that 62% of eligible unregistered voters reported they had never been asked to register.[92]

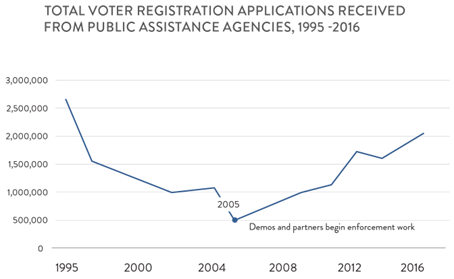

One common explanation for why the NVRA has not been more effective is that it did not provide states with funding to implement voter registration activities.[93] However, the NVRA was highly effective at boosting voter registration rates in the first several years after the law took effect.[94] By contrast, the years between 1995 and 2005 saw a dramatic decline in the effectiveness of the NVRA, particularly in the number of voters registered at Section 7 public assistance agencies.[95] This pattern of initial success followed by a steep decline is better explained by States being unwilling—rather than unable—to effectively implement the NVRA.

III. Additional Enforcement is Required to Achieve the Purposes of the NVRA

Beginning immediately after the passage of the NVRA, state governments have waged a continuous campaign of challenging the NVRA in court and refusing to administer the Act effectively. To counter this resistance, the Justice Department[96] and non-profit organizations[97] have made extensive use of the civil right of action provided by the NVRA to force States to comply.[98] These efforts have been generally successful in court and have resulted in millions of citizens registering to vote.[99] The success of these enforcement efforts and the continuing State resistance demonstrate that further enforcement could help achieve the NVRA’s purpose of maximizing voter registration opportunities.[100] Since the NVRA establishes that the federal government has a duty to promote the fundamental right of citizens to vote,[101] the Justice Department should expand its current enforcement efforts against States that fail to comply with the NVRA.[102]

A. States have consistently resisted complying with the NVRA

The campaign of State resistance to the NVRA first manifested in repeated challenges to the constitutionality of the NVRA. California was the first State to refuse to implement the NVRA, arguing that, under the 10th Amendment, Congress did not have the authority to require States to register voters.[103] Wilson v. United States rejected this argument because Article I, Section 4 of the Constitution expressly grants Congress the power to regulate the “time, place, and manner” of federal elections.[104] However, this did not stop Rhode Island, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, New York, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Vermont, Virginia, and Illinois from mounting their own unsuccessful challenges to the constitutionality of the NVRA in various cases between 1995 and 2000.[105]

This string of resounding court losses would seem to put an end to this line of argument. However, New York again challenged the constitutionality of the NVRA in 2010.[106] New York was again rejected, with the District Court for the Northern District of New York noting that the “proverbial ship on that issue has long sailed.”[107] Undeterred, Arizona took a shot at overturning the constitutionality of the NVRA in 2013.[108] The Supreme Court rejected this attempt, too, stating that “[w]hen Congress legislates with respect to the ‘Times, Places and Manner’ of . . . elections, it necessarily displaces [the] legal regime erected by the States.”[109] Further, the Court noted that “the power the Elections Clause confers is none other than the power to pre-empt” state law.[110]

This extremely clear holding by the Supreme Court did not stop Louisiana from challenging the constitutionality of the NVRA in 2016.[111] An apparently exasperated District Court for the Middle District of Louisiana noted that Louisiana “misconstrues the NVRA’s constitutional basis.”[112] As “history attests and as courts have recognized, the NVRA was deliberately and expressly anchored in the Elections Clause.”[113] The court concluded that “it is well settled that the Elections Clause grants Congress ‘the power to override state regulations’ by establishing uniform rules for federal elections, binding on the States.”[114]

Given the extensive body of case law upholding Congress’ powers under the Elections Clause and the constitutionality of the NVRA, it is difficult to believe that these States had any real expectation of succeeding in their constitutional claims. These challenges are better explained by State governments simply dragging their feet on implementing the provisions of the NVRA. This interpretation is strengthened by the creative and persistent attempts by State governments to resist implementing the NVRA in general and Section 7 in particular.

Many States were slow to implement the NVRA. Two years after the NVRA passed, twenty-five states had designated only a single voter registration agency under Section 7; four states had refused to designate any.[115] Despite the NVRA becoming law in 1993, Mississippi did not implement Section 7 until 2000, and only then because a court ordered the State to do so.[116]

The foot-dragging continued even after States, in theory, implemented the NVRA. In Nevada, for example, the number of voter registrations at public assistance agencies fell by 95% between 2001 and 2010.[117] During that same period, the number of food stamp applications —which, under the NVRA, require the provision of voter registration forms—increased by over 400%.[118] If Nevada’s implementation of the NVRA had been effective, the rising food stamp applications should have caused an increase in voter registrations, not a precipitous decline.

Arizona attempted to evade the NVRA by banning the voter registration forms mandated by the NVRA, creating new voter registration forms requiring registrants to prove their citizenship.[119] The 9th Circuit Court of Appeals noted that “Arizona has offered a creative interpretation of the state and federal statutes” but invalidated the law as “inconsistent with the plain language” of the NVRA.[120]

Instead of accepting this loss and using the voter registration forms mandated by the NVRA, Arizona took the case to the Supreme Court in its doomed attempt to challenge the constitutionality of the NVRA.[121] Highlighting the futility of Arizona’s constitutional claims, noted States-rights advocate Justice Scalia penned the opinion upholding the NVRA.[122] Scalia was joined by Justice Roberts, who (that same year) wrote the opinion in Shelby County v. Holder, which struck down a major portion of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 on constitutional grounds.[123]

Louisiana also invented creative and ultimately illegal policies to avoid registering voters at public service agencies.[124] The NVRA requires Section 7 VRAs to provide a mail voter registration form during “each application for…service or assistance, and with each recertification, renewal, or change of address.”[125] However, Louisiana provided voter registration forms only to in-person applicants for public assistance and not to applicants who applied online or over the phone, even though Louisiana relied “extensively on remote means to interact with public assistance clients.”[126] The District Court for the Middle District of Louisiana found that the States’ interpretation would “directly undermine” the NVRA’s objective of “maximizing opportunities for voter registration.”[127]

Louisiana also unsuccessfully argued that, while the NVRA required the State to designate VRAs, it did not require States to ensure that the VRAs actually registered voters. The court noted that a State “cannot evade its obligations under federal law by means of delegation.”[128] Louisiana’s evasive maneuvers are even more striking, considering that the State was already under an injunction issued by the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals for refusing to comply with the requirements of the NVRA.[129]

States have also attempted to undermine the NVRA by narrowly interpreting which State agencies must be voter registration agencies under Section 7.[130] Ohio’s refusal to provide voter registration at county public assistance agencies was struck down by the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals.[131] Virginia’s refusal to provide voter registration services at the disability offices of state colleges was struck down by the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals.[132] This ruling did not stop New York from implementing a nearly identical policy and taking the same losing arguments to the Northern District of New York.[133]

The interminable legal battles to force States to comply with the NVRA can seem like a game of Whack-A-Mole. Since the passage of the NVRA, the U.S. Justice Department has sued or reached settlement agreements with 25 different states—some multiple times—to compel compliance with the NVRA.[134] Non-profit organizations have initiated many more legal actions.[135] However, this endless litigation has not been in vain. In fact, enforcement efforts have had a tremendous impact on the effectiveness of the NVRA in increasing voter registration.[136]

B. Enforcing Section 7 is an Effective Means of Increasing Voter Registration

The steep decline in voter registration rates in the years after the passage of the NVRA called into question its effectiveness and design. In 1995, over 2.5 million voters were registered at Section 7 VRAs per year, but by 2005, new registrations had fallen to below 500,000 per year.[137] However, the legal battles over the enforcement have substantially restored the effectiveness of Section 7,[138] demonstrating that the falling registration rates were a matter of compliance, not design.

Starting in 2005, non-profit organizations led by Demos began a national campaign to use the NVRA’s civil right of action provision to force States to comply with the NVRA.[139] This campaign has had dramatic results. In just over ten years, the annual number of voter registrations at public assistance agencies rose by over 400%.[140] Demos estimates that its enforcement campaign was directly responsible for registering over 3,044,000 voters over that period.[141] The following graph of Section 7 voter registration before and after the enforcement campaign highlights that enforcement of the NVRA is key to its long-term success. Further, it clearly indicates that the fall in voter registration rates was caused by State resistance, not by any inherent problem with the design of the NVRA.

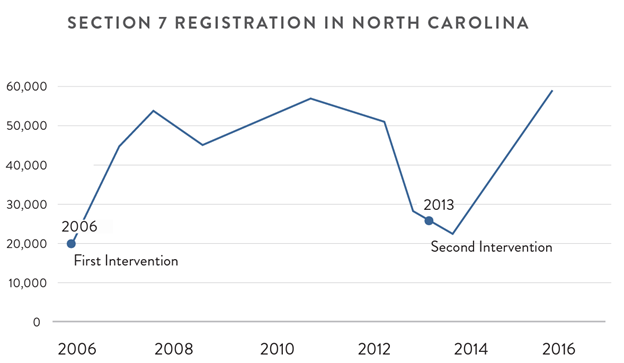

Even more telling are the results of Demos’s enforcement efforts in North Carolina. In 2006, Section 7 VRAs in North Carolina only registered around 20,000 voters per year, a 73% decline since 1996.[142] Demos conducted studies, found that North Carolina was badly out of compliance with the NVRA, and brought their findings to the attention of North Carolina election officials.[143] Through active collaboration with Demos and Project Vote, North Carolina’s annual registrations at Section 7 VRAs almost tripled over the next six years.[144] However, in 2012, a new State administration took over, and voter registration numbers at Section 7 agencies plunged back to the levels from 2006. This time, Demos took North Carolina to court and won an injunction ordering the State to comply with the NVRA.[145] Within three years, voter registrations almost tripled again.[146] Opposition by elected officials to implementing the NVRA is the only reasonable explanation for why Section 7 registrations plummeted and then recovered in North Carolina between 2012 and 2016.

The long history of State resistance to implementing the NVRA, and the success of litigation at forcing State compliance, suggest that increased enforcement is necessary to achieve the NVRA’s purpose of maximizing opportunities for voter registration.[147]Enforcing Section 7 would effectively increase voter registration rates.[148]Increased voter registration rates would lead to higher levels of democratic participation because U.S. citizens consistently vote at high rates once they have registered.[149]Worldwide, democracies with higher participation rates in elections tend to have better-performing government institutions and lower levels of social inequality.[150]While this correlation does not show that the increased participation caused improved government performance, it is no great leap to conclude that governments provide better service when they are more accountable to voters.

Increasing the number of Voter Registration Agencies is an effective means of boosting voter registration rates.[151] One of the anomalies of state implementation of the NVRA is that Public Housing Authorities (PHAs) have never been designated as VRAs.[152] PHAs are state agencies that provide federal housing aid to needy families.[153] PHAs appear to be a perfect fit for the NVRA’s requirement that States designate as VRAs “all offices in the state that provide public assistance.”[154] The following analysis of the legal structure of PHAs and past court interpretations of the NVRA confirm that States are failing to comply with federal election law by not designating PHAs as VRAs. Enforcement of this requirement would effectively increase voter registration rates and further the purposes of the NVRA.

IV. NVRA Section 7 Applies to Public Housing Authorities

PHAs are State-created agencies that administer federal housing aid programs funded by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).[155] The primary housing assistance programs administered by PHAs are the Public Housing Program and the Housing Choice Voucher Program.[156] Both are HUD-funded programs that subsidize housing costs for low-income individuals based on the needs of applicants.[157] PHAs administer these HUD-funded programs by reviewing applications, conducting background and credit checks on applicants, providing information about program policies and procedures to current and prospective recipients, and updating the documentation of recipients’ eligibility.[158] PHAs also develop, acquire, lease, and operate public housing projects, all funded by HUD programs.[159] However, HUD does not directly dictate the action of PHAs.[160] Instead, PHAs have contracts with HUD to provide specific services in exchange for receiving HUD funding.[161]

Nationwide, there are over 3,300 PHAs.[162] PHAs administer aid from HUD programs to almost 5 million households.[163] Recipients of housing aid through HUD programs have an average annual income of $15,846, and 46% are Black or African American.[164]

No state currently designates PHAs as VRAs. However, the plain text and legislative history of Section 7 indicate that PHAs meet the criteria to be mandatory voter registration agencies under the NVRA. Designating PHAs as VRAs would further Congress’ explicit intent to “increase the number of eligible citizens who register to vote” and to implement the Act in “a manner that enhances the participation of eligible citizens as voters.”[165] Therefore, the U.S. Attorney General and private citizens should sue states that refuse to designate PHAs as VRAs.[166]

A. Public Housing Authorities are Offices in the State that Provide Public Assistance

Section 7 of the NVRA requires that “[e]ach State shall designate as voter registration agencies…all offices in the State that provide public assistance.”[167] This is the only requirement for determining which offices States must designate as Mandatory VRAs under Section 7. The terms “offices in the State” and “public assistance” are not defined under the NVRA, and few court cases have interpreted the precise meaning of this clause.[168] However, litigation over other sections of the NVRA has established statutory interpretation principles and identified key legislative history that would apply to Section 7. Using the methods developed by prior caselaw demonstrates that PHAs are “offices in the State that provide public assistance.”[169] Therefore, Section 7 of the NVRA requires States to provide voter registration services at PHAs to applicants for federal housing aid.

1. Statutory Interpretation Methods from NVRA Case Law

Very few court cases have interpreted the precise meaning of the VRA provisions of Section 7. Almost none have considered whether States need to designate additional offices as VRAs. Given this paucity of precedent, any court considering whether PHAs qualify as Mandatory VRAs would likely build on the established methodology for interpreting other sections of the NVRA.

Courts interpreting the NVRA utilize a two-step process. First, interpretation of the NVRA “begins with the language of the statute.”[170] Courts “assume that the words Congress chose, if not specially defined, carry their plain and ordinary meaning,”[171] usually determined based on dictionary definitions.[172] When the statute’s language is plain, courts “enforce it according to its terms.”[173] Courts will reject legal interpretations inconsistent with the plain language of the NVRA, ending the analysis.[174]

Second, if the statute’s language is ambiguous, courts consider Congress’ intent when drafting the NVRA.[175] To do so, courts employ “the traditional tools of statutory construction, including a consideration of the language, structure, purpose, and history of the statute…in their context and with a view to their place in the overall statutory scheme.”[176]

Valdez v. Squier demonstrates the first part of this two-step analysis. Valdez interpreted the requirement that voter registration agencies must provide mail voter registration forms “unless the applicant, in writing, declines.”[177] Application forms at the New Mexico Human Service Department (NM HSD) asked if applicants wanted to register to vote and provided checkboxes for “yes” and “no.”[178] NM HSD only provided mail voter registration forms when the applicants checked yes, but not when they checked no or failed to check either box.[179]

Valdez found that NM HSD violated the NVRA by failing to provide mail voter registration forms to applicants who failed to check either box.[180] Because the NVRA does not define the term “in writing,” the court consulted the Oxford English Dictionary and found that it is commonly defined to mean “written form.”[181] Based on this definition, the court held that voter registration forms must be provided “unless the applicant declines, in written form.”[182] The court held that failing to check a box was “clearly at odds with the ordinary meaning” of the phrase “in written form.”[183] Consequently, HSD’s interpretation was “directly rebutted” by the language of the statute.[184] The court concluded that if Congress had intended for an applicant’s failure to check either box to relieve the agency of its obligation to provide a voter registration form, “it presumably would have said so.”[185] Since the text’s plain meaning was dispositive, the court did not continue the analysis further.

Project Vote, Inc. v. Kemp demonstrates the second part of the two-step process.[186] Project Vote considered whether Section 8 of the NVRA, which requires States to disclose records concerning the “implementation of programs and activities” at VRAs, included individual voter registration applications.[187] The court consulted three different dictionaries but found that depending on different definitions of “implement,” the particular records “may or may not fall under the common and ordinary meaning of Section 8(i).”[188] Therefore, the court moved to the second step of the analysis, considering legislative history and context to resolve the ambiguity.[189]

The court started by establishing that the “primary emphasis” of the NVRA is to “simplify the methods for registering to vote…and maximize such opportunities for a state’s every citizen.”[190] Further, the NVRA was “designed to ensure that eligible applicants in fact are registered.”[191] The court found that limiting the disclosure requirement would hinder the public’s ability to ensure that voting registration programs accomplish the purposes of the statute.[192] Therefore, Section 8’s place in the NVRA as a whole required States to disclose individual applicant records.[193]

2. Court Interpretations of NVRA Section 7

Courts interpreting the statutory text of Section 7 have used the same two-step process. Nat’l Coal. v. Allen considered whetherthe NVRA requirement that States designate as VRAs “all offices in the State that provide State-funded programs primarily engaged in providing services to persons with disabilities” applied to offices in public colleges that assisted students with disabilities.[194] This case is instructive because the statutory language “all offices in the State that provide” from 52 U.S.C. §20506(a)(2)(B) is identical to the first portion of the requirement that States designate as VRAs “all offices in the State that provide public assistance” from 52 U.S.C. §20506(a)(2)(A).

Allen turned on the interpretation of the word “office.”[195] First, the court analyzed the plain text of the statute. Virginia argued that the entirety of the public college was an “office,” so the “office” was not “primarily engaged in providing services to persons with disabilities.”[196] The National Coalition for Students with Disabilities (NCSD) countered that Websters and other dictionaries defined “office” in a governmental context as “a subdivision of a governmental department.”[197] NCSD used this definition to argue that the college’s department providing services for students with disabilities was the office, not the whole college.[198] Virginia pointed to one definition from Random House that defined “office” as “a major administrative unit” as in “the Foreign Office.”[199] The court found that these conflicting definitions created ambiguity and turned to the second analytical step, considering the meaning of the word “offices” in the “context of the statute as a whole.”[200]

The court noted that (under a different paragraph of Section 7) States may voluntarily designate other government offices as VRAs, including public libraries, public schools, and offices of city and county clerks.[201] From these examples, the court determined that Congress’ focus was on “locations where citizens conduct their daily business with government” because the high citizen traffic was ideal for providing voter registration services.[202] The court concluded, that in the broader context of the NVRA, an office is a “subdivision of a department where citizens regularly go for service and assistance.”[203]

The court then turned to legislative history, noting that Congress’s purpose in drafting Section 7 was to “provide adequate voter registration opportunities to citizens who may not apply for or renew driver’s licenses.”[204] The court extensively quoted the House Conference Report, which is commonly quoted by cases interpreting the NVRA.[205]

According to the House Report, the office designation section of the Act is designed to “supplement the motor-voter provisions of the bill by reaching out to those citizens who are likely not to benefit from the State motor-voter application provisions.” Offices serving the disabled and recipients of public assistance were identified as the offices “most likely to serve the person of voting age who may not have driver’s licenses.” By requiring states to designate these offices as voter registration agencies, “we will be assured that almost all of our citizens will come into contact with an office at which they may apply to register to vote with the same convenience as will be available to most other people under the motor voter program of this Act.”[206]

Based on this legislative history and context, the court concluded that offices providing services to disabled students at public colleges must be designated as VRAs because “[s]uch an office, as a subdivision of the college, fits the plain meaning of ‘office’” under the NVRA.[207]

Disabled in Action v. Hammons similarly used legislative history to resolve ambiguity when it found that the statutory text was unclear.[208] Hammons is one of the only cases interpreting the phrase “provide public assistance” under Section 7 of the NVRA.[209] At issue was whether hospitals that assisted patients in applying for Medicare were “offices in the State that provide public assistance.”[210] The court found that private hospitals cannot be “offices in the state” because they are not governmental agencies.[211] Conversely, public hospitals operated by New York City were “offices of local government” and, therefore, must be designated as VRAs.[212]

New York argued that, even if the public hospitals were “offices in the state,” they were not providing “public assistance.”[213] Medicare is “medical assistance,” which is defined under federal law as “payment of part or all of the cost” of medical services.[214] New York argued that the offices did not “provide public assistance” because they only “provide medical services or assist applicants with Medicaid applications…rather than provide payment for those services.”[215] The court rejected this argument, stating that the “drafters of the NVRA intended the phrase ‘public assistance’ to have a broader meaning that includes not only the payment process but the application process as well.”[216]

The court supported this statement by quoting extensively from the legislative history, particularly the House Conference Report, noting that “next to the statute itself,” a conference report is “the most persuasive evidence of congressional intent.”[217] The court focused on the report’s statement that “[b]y public assistance agencies, we intend to include those State agencies…that administer or provide services under the food stamp, [M]edicaid, the Women, Infants and Children (WIC), and the Aid to Families With Dependent Children (AFDC) programs.”[218] The court also noted the conference report’s statement that “public assistance agencies will help register more people” because “these government agencies…will be able to assist people in registering.”[219] The court concluded that State-run hospitals that provided Medicaid application forms, assisted applicants in completing the forms, or interviewed Medicaid applicants must be designated as VRAs under Section 7.[220]

3. Application of Principles to Public Housing Authorities

Prior case law has created a blueprint with which to analyze whether Public Housing Authorities should be designated as Voter Registration Agencies under Section 7. Using the two-step analysis from NVRA case law shows that the plain text and the legislative history of Section 7 indicate that public housing authorities are “offices in the State” and that they “provide public assistance.”[221] Therefore, any State that does not designate PHAs and VRA is out of compliance with the NVRA.

a) Public Housing Authorities are “Offices in the State.”

The first step of the analysis is to determine whether the ordinary and plain meaning of the term “offices in the state” encompasses public housing authorities. The Housing Act of 1937 (which established HUD) defines “public housing agency” as “any State, county, municipality, or other governmental entity or public body (or agency or instrumentality thereof) which is authorized to engage in or assist in the development or operation of public housing.”[222] However, Public Housing Authorities are created by state law, not the Housing Act of 1937.[223] For example, the Pennsylvania Housing Authorities Act established “the policy of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to promote the health and welfare…by the creation of…housing authorities.”[224] The Act further states that “[a]n Authority shall constitute a public body, corporate and politic, exercising public powers of the Commonwealth as an agency thereof.”[225] This text clearly indicates that PHAs fit the ordinary and plain meaning of “offices in the State” because they are State government agencies.[226]

PHAs also fit the ordinary and plain meaning of “offices.” Black’s Law Dictionary defines “office” as a “place where business is conducted or services are performed.”[227] Similarly, Merriam-Webster defines “office” as “a place where a particular kind of business is transacted or a service is supplied: such as a place in which the functions of a public officer are performed.”[228] PHAs have physical offices where government employees work in the business of providing public housing aid.[229] The Philadelphia Housing Authority, for example, invites potential applications to “visit the Admissions office at 2013 Ridge Avenue.”[230]

Public Housing Authorities also fit the definition of “offices” provided by Nat’l Coal. v. Allen, which held that, in the context of the NVRA, offices are “a subdivision of a department where citizens regularly go for service and assistance.”[231] PHAs have many functions not involving the administration of aid to HUD program recipients, such as leasing, maintaining, and developing properties.[232] Therefore, the departments of PHAs that administer HUD programs—such as the Philadelphia Housing Authority’s Leased Housing Department, which administers the Housing Choice Voucher Program—are a subdivision of a State government agency.[233] PHA offices are also places where “citizens regularly go for service and assistance.”[234] The Philadelphia Housing Authority’s Leased Housing Department alone “assists over 44,000 citizens involved in the Housing Choice Voucher Program.”[235] The main goal of the department is to “provide exceptional customer service.”[236]

This evidence clearly shows that Public Housing Authorities fit the common and ordinary meaning of the term “offices in the state.”[237] Therefore, a court interpreting this section should require no further analysis.[238] However, if a court found that there was ambiguity, a consideration of the legislative history of Section 7 also shows that PHAs are the type of office that Congress intended to be voter registration agencies.

The House Conference Report expressed a concern that States would “restrict their agency program and defeat a principal purpose of this Act–to increase the number of eligible citizens who register to vote.”[239] The report notes that restricting the number of voter registration agencies would exclude “the poor and persons with disabilities who do not have driver’s licenses” from voter registration.[240] The report explicitly states that the intent of Section 7 was to ensure that States designated VRAs that would have “regular contact with those who do not have driver’s licenses.”[241]

Citizens receiving public housing assistance from PHAs are predominantly from the demographics that are least likely to have driver’s licenses. Individuals with an annual household income lower than $25,000 are the least likely to have driver’s licenses compared to all other income brackets.[242] More than 27% of Black individuals do not have driver’s licenses.[243] More than 37% of Black individuals with an annual household income of less than $25,000 do not have driver’s licenses.[244] Recipients of housing aid through HUD programs have an average annual income of $15,846, and 46% are Black or African American.[245] Further, in 2010, over 49% of recipients of HUD housing vouchers were elderly or disabled.[246] Therefore, PHAs serve and have regular contact with “the poor and persons with disabilities who do not have driver’s licenses” that Congress had in mind when drafting Section 7.[247]

In conclusion, both the plain text of the NVRA and the legislative history and Congressional intent of Section 7 indicate that Public Housing Authorities are “Offices in the State.”[248] Therefore, if PHAs provide public assistance, they meet the only requirements under Section 7 to qualify as mandatory voter registration agencies.

b) Public Housing Authorities “Provide Public Assistance.

Interpreting the meaning of “offices that provide public assistance” follows the same two-step analysis.[249] This analysis shows that the ordinary and plain meaning of the statutory term “provide public assistance” encompasses public housing aid.[250]

The NVRA does not define “public assistance.”[251] Consequently, courts interpreting Section 7 use the common canon of statutory construction that if “Congress does not explain the specific meaning of a statutory term, the Court should assume that Congress intended the word to be given its ordinary meaning, ‘which we may discover through the use of dictionaries.’”[252] Black’s Law Dictionary defines “public assistance” as “[a]nything of value provided by or administered by a social-service department of government; government aid accorded to needy people.”[253] Similarly, Merriam-Webster defines “public assistance” as “government aid to needy, aged, or disabled persons and to dependent children.”[254]

These dictionary definitions closely match the usage of the term by government agencies. The U.S. Census Bureau states that “Public assistance refers to assistance programs that provide either cash assistance or in-kind benefits to individuals and families from any governmental entity . . . usually based on a low income means-tested eligibility criteria”[255] The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (which sets nationwide standards for State workforce development programs) defines “public assistance” as “Federal, State, or local government cash payments for which eligibility is determined by a needs or income test.”[256] Bankruptcy courts have defined “public assistance” as “financial aid to lower income individuals and families.”[257]

Based on these definitions, federal housing aid programs are public assistance. The Housing Act of 1937 authorizes HUD to provide “assistance payments . . . [f]or the purpose of aiding low-income families in obtaining a decent place to live.”[258] These monthly assistance payments directly benefit program recipients by making up the difference between the cost of providing housing for tenants and the subsidized rent payments made by the tenants.[259] Similarly, the Housing Choice Voucher Program authorizes PHAs to make “tenant-based assistance” payments directly to landlords on behalf of voucher recipients.[260] Tenant-Based Assistance is defined as “rental assistance…that provides for the eligible family to select suitable housing.” Further, eligibility to receive assistance under HUD programs is established using income-based criteria.[261] Based on this statutory language, federal housing assistance is clearly a payment of government aid to or on behalf of needy persons. Therefore, housing assistance fits the ordinary and common definition of “public assistance.”

Public Housing Authorities also “provide” this public assistance to program recipients. In Disabled in Action v. Hammons, the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals rejected New York’s argument that public hospitals did not “provide” public assistance because they only assisted applicants with their Medicaid applications and did not pay the Medicaid payments.[262] Instead, the court stated that the “drafters of the NVRA intended the phrase ‘public assistance’ to have a broader meaning that includes not only the payment process, but the application process as well.”[263] PHAs review applications for HUD programs, determine the eligibility of applicants, and assist applicants by providing information on program policies.[264] Therefore, PHAs are clearly involved in the application process and provide public assistance as defined in Hammons.

Even if a court determined that there was ambiguity in the definition of the term “provide public assistance,” the legislative history and context of Section 7 also support the conclusion that PHAs “provide public assistance.” The NVRA explicitly states that “it is the duty of the Federal, State, and local governments to promote the exercise” of citizens’ fundamental right to vote.[265] Many courts have held that the “primary emphasis” of the NVRA is to “maximize” the opportunities for “every citizen” to register to vote.[266] Given this broad and clear language, there is no reason to think that Congress intended Section 7 to be interpreted narrowly.

Instead, there is clear evidence that Congress intended to ensure that Section 7 was not interpreted narrowly by States. The Conference Committee rejected a Senate amendment that would have made VRA designations discretionary instead of mandatory.[267] The report notes that the “conference is concerned that the Senate amendment would permit States to restrict their agency program and defeat a principal purpose of this Act.”[268] Congress’ main concern was that Section 7 should be effective, not that it should be limited.

The only evidence in the legislative history that could be interpreted as narrowing the scope of Section 7 was the Committee’s statement that “[b]y public assistance agencies, we intend to include those State agencies…that administer…the food stamp, [M]edicaid, the Women, Infants and Children (WIC), and the Aid to Families With Dependent Children (AFDC) programs.”[269] Many States appear to view this list as exclusive,[270] vigorously resisting efforts to include additional State agencies under Section 7.[271]

However, there is no reason to believe that the Conference Committee intended this list to be exclusive. The Committee was concerned that States would restrict their voter registration agency programs, not that States would designate too many offices as VRAs.[272] Further, the Report states that Section 7 was intended “to include” these agencies, not to limit Section 7 to that list of agencies.[273] If Congress had intended Section 7 agencies to be strictly limited to an enumerated list, “it presumably would have said so” in the statute.[274] This is especially true considering that the NVRA contains a definitions section that does not define public assistance.[275] This section could easily have provided an enumerated list if Congress had wanted to limit Section 7 with a narrow definition.[276]

In fact, the list of agencies in the committee report is additional evidence that PHAs are the type of office that Congress had in mind when drafting Section 7. Both WIC and SNAP (the new name for the Food Stamp Program) have an almost identical legal structure to HUD, with federal benefits being provided to needy individuals by state agencies in the form of subsidies for purchases of basic human needs.[277] The similarity between HUD and these programs further indicates that PHAs meet the requirements of Section 7.

Courts interpreting the NVRA also consider the context and purpose of the whole statute to determine the meaning and application of ambiguous text.[278] The “obvious and well-known purposes” of the NVRA are to establish the “duty of the Federal, State, and local governments to promote the exercise” of the right of citizens to vote.[279] To effectuate these purposes, the NVRA establishes procedures to “increase the number of eligible citizens who register to vote.”[280] Therefore, if designating Public Housing Agencies as voter registration agencies would increase the number of citizens who are registered to vote, doing so would further the goals that NVRA set out to accomplish.

B. Providing Voter Registration Services at Public Housing Authorities Would Effectuate the Purposes of the NVRA

Designating Public Housing Authorities as voter registration agencies would be an effective means of increasing voter registration.[281] PHAs predominantly provide services to low-income families and racial minorities. [282] These groups are less likely to be registered to vote,[283] more likely to change address often (which necessitates updating voter registration), [284] and less likely to register to vote at a Department of Motor Vehicles.[285] Further, there are over 3,300 PHAs nationwide,[286] providing services to almost 5 million households.[287]

Based on the number and demographics of the people served by PHAs, designating them as Voter Registration Agencies would provide voter registration services to a huge number of individuals and reach the individuals most in need of voter registration services. This reach is even greater because, under Section 7, VRAs must provide voter registration services to everyone who applies for assistance—not just to those who qualify for service.[288] For example, when the Philadelphia Housing Authority opened its housing voucher waitlist in January 2023, it received over 37,000 applications for just 10,000 waitlist spots.[289] If the Philadelphia Housing Authority was a VRA, it would have had to provide voter registration services to all 37,000 applicants, not just the 10,000 accepted to the waitlist.[290] PHAs are also in contact with individuals when they move to new addresses, making them particularly well suited to providing voter registration services. Taken together, all the evidence indicates that PHA would be very effective at increasing the number of citizens who are registered to vote. Therefore, interpreting “offices in the states that provide public assistance” as including Public Housing Authorities fits the overall purpose and context of NVRA Section 7.

V. Conclusion

In conclusion, Congress passed the NVRA to increase democratic participation and correct historically unjust State voter registration laws. The primary means Congress chose was by providing voter registration at State Departments of Motor Vehicles. However, Congress feared that this measure would exclude low-income and disabled persons from voter registration programs.[291] To correct the issue, Congress included Section 7 to maximize the number of citizens registering to vote.[292]

Analysis of Section 7 shows that the plain text of the NVRA requires States to designate Public Housing Authorities as Voter Registration Agencies. This conclusion is reaffirmed by the legislative history and statutory context of the NVRA. However, as part of a broad campaign of resistance to implementing the NVRA, States have failed to designate PHAs as Voter Registration Agencies. This failure violates federal law.

As Congress proclaimed in the NVRA: “[T]he right of citizens of the United States to vote is a fundamental right…it is the duty of the Federal, State, and local governments to promote the exercise of that right.”[293] The Department of Justice has a statutory cause of action to sue States for failure to comply with the NVRA.[294] Designating PHAs as VRAs would effectively further the purposes of the NVRA, so the DOJ has a legal duty to enforce State compliance with this requirement. Private individuals and voting rights organizations also have a statutory right to sue states under the NVRA. Either federal or private legal action to require States to designate Public Housing Authorities as Voter Registration Agencies would be a practical and achievable means of increasing democratic participation and broadening the diversity of the electorate.

*Arlo Blaius, J.D. Candidate at Temple University Beasley School of Law, 2024. I thank Professor Nancy Knauer for her invaluable advice, feedback, and inspiration throughout the course of this project. I thank all my friends and colleagues at the Temple Political and Civil Rights Society for their assistance in writing and publicizing this Article. In particular, I thank Billy February, Andrew Holland, Tejal Mejethia, Adamari Rodriques, and Angela Lu for their excellent editing suggestions. Most importantly, I thank my steadfast partner, Alison Dalbey, for the innumerable ways in which she supports and encourages me every day.

[1] Naila S. Awan, When Names Disappear: State Roll-Maintenance Practices, 49 U. Mem. L. Rev. 1107, 1143 (2019).

[2] Drew Desilver, In Past Elections, U.S. Trailed Most Developed Countries in Voter Turnout, Pew Research Center, (2020) [hereinafter In Past Elections] https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/11/03/in-past-elections-u-s-trailed-most-developed-countries-in-voter-turnout/.

[3] Russell J. Dalton, Is Citizen Participation Actually Good for Democracy?, Democracy Audit UK (2017) https://www.democraticaudit.com/2017/08/22/is-citizen-participation-actually-good-for-democracy/ (last visited 8/7/2022).

[4] Laura Williamson, Pamela Cataldo & Brenda Write, Toward a More Representative Electorate: The Progress and Potential of Voter Registration through Public Assistance Agencies 4 (2018), https://www.demos.org/research/toward-more-representative-electorate.

[5] United States v. Louisiana, 196 F. Supp. 3d 612, 670 (M.D. La. 2016).

[6] Kimberly C. Delk, What Will it Take to Produce Greater American Voter Participation? Does Anyone Really Know?, 2 Loy. J. Pub. Int. L. 133, 157 (2001).

[7] See Motor Voter Law, Pennsylvania Department of Motor Vehicles, https://www.dmv.pa.gov/Information-Centers/Laws-Regulations/Pages/Motor-Voter-Law.aspx (Last visited 8/8/22).

[8] See 52 U.S.C. § 20506.

[9] See H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 103–66, at 19 (1993).

[10] Williamson, Cataldo, and Write, supra note 4, at 7.

[11] Desilver, In past elections, U.S. trailed most developed countries in voter turnout, supra, note 2.

[12] Jacob Fabina and Zach Scherer, Voting and Registration in the Election of November 2020, at 3, U.S. Census Bureau, (2022) https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2022/demo/p20-585.html.

[13] Id at 8.

[14] See Jennifer Cheeseman Day and Thom File, Most People Who Are Registered to Vote Actually Do Vote, U.S. Census Bureau, (2020), https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2020/10/what-can-recent-elections-tell-us-about-the-american-voter-today.html.

[15] Drew Desilver, Turnout in U.S. has Soared in Recent Elections but by Some Measures Still Trails that of Many Other Countries, Pew Research Center (Nov. 1, 2022), https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/11/03/in-past-elections-u-s-trailed-most-developed-countries-in-voter-turnout/.

[16] See, supra Section III.A.

[17] Id.

[18] 52 U.S.C. § 20506(a).

[19] See, e.g., Ga. State Conf. of the NAACP v. Kemp, 841 F. Supp. 2d, 1320, 1324 (N.D. Ga. 2012) (noting that Georgia’s statute implementing the NVRA only designates offices providing food stamp; Medicaid; Women, Infants, and Children; and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families programs as VRAs).

[20] See, Williamson, Cataldo, and Write, Supra, note 4 at 19.

[21] See, supra Section IV.A.

[22] See, Supra Section IV.B.

[23] 52 U.S.C. § 20501(b)(1).

[24] See, supra Section II.

[25] See, supra Section III.

[26] See, supra Section IV.

[27] Id.

[28] See, supra Section V.

[29] See Dayna L. Cunningham, Who Are to Be the Electors? A Reflection on the History of Voter Registration in the United States, 9 Yale Law & Pol’y Rev., 370, 372 (1991); Awan, supra note 1, at 1143.

[30] See Desilver, In Past Elections, supra note 2.

[31] See Cunningham, supra note 29, at 374.

[32] Voting Rights Act of 1965, Pub. L. No. 89-110, 79 Stat. 437.

[33] 52 U.S.C. § 20501.

[34] See Voting Rights Act (1965), National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/voting-rights-act#:~:text=This%20act%20was%20signed%20into,as%20a%20prerequisite%20to%20voting. (last accessed 8/8/22) (The VRA “outlawed the discriminatory voting practices adopted in many southern states after the Civil War, including literacy tests as a prerequisite to voting.”); 52 U.S.C. § 20501(a) (“Congress finds that… discriminatory and unfair registration laws and procedures can have a direct and damaging effect on voter participation in elections for Federal office and disproportionately harm voter participation by various groups, including racial minorities.”).

[35] Fabina & Zach Scherer, supra note 12, at 3.

[36] Cunningham, supra note 29, at 373.

[37] Id.

[38] See Delk, supra note 6 at 138.

[39] Id.

[40] See Derek T. Muller, What’s Old Is New Again: The Nineteenth Century Voter Registration Debates and Lessons About Voter Identification Disputes, 56 Washburn L.J. 109, 100 (2017).

[41] Cunningham, supra note 29 at 374.

[42] Id.

[43] See (1898) Louisiana Grandfather Clause, Black Past, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/1898-louisiana-grandfather-clause/ (last accessed 8/8/22).

[44] Cunningham, supra note 29 at 374 (quoting Francis T. Nicholls, former Governor of Louisiana and then Chief Justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court calling the Constitutional Convention to order)

[45] Id. (quoting United States v. Louisiana, 225 F. Supp. 353, 373 (E.D. La. 1963) (quoting the President of the Convention, Ernest B. Kruttschnitt stating that “[w]e are all aware that this Convention has been called…to eliminate from the electorate the mass of corrupt and illiterate voters who have during the last quarter century degraded our politics.”).

[46] Id. at 380.

[47] Id.

[48] See Muller, supra note 40 at 110.

[49] Cunningham, supra note 29 at 381.

[50] Id. at 373.

[51] Muller, supra note 40 at 110.

[52] Cunningham, supra note 29 at 384.

[53] See id.

[54] Or, more likely, because of it.

[55] Muller, supra note 40 at 111.

[56] See Delk, supra note 6 at 141.

[57] Id.

[58] Cunningham, supra note 29 at 388.

[59] Id.

[60] See Civil Rights Act of 1964, Ballotpedia, https://ballotpedia.org/Civil_Rights_Act_of_1964#:~:text=Johnson%20on%20July%202%2C%201964,discourage%20racial%20segregation%20in%20schools (Last accessed 8/8/22).

[61] See Voting Rights Act (1965), National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/voting-rights-act#:~:text=This%20act%20was%20signed%20into,as%20a%20prerequisite%20to%20voting. (noting that the VRA “outlawed the discriminatory voting practices adopted in many southern states after the Civil War, including literacy tests as a prerequisite to voting”) (last accessed 8/8/22).

[62] Cunningham, supra note 29 at 388.

[63] United States v. Louisiana, 196 F. Supp. 3d 612, 626 (M.D. La. 2016).

[64] Delk, supra note 6 at 150.

[65] Id.

[66] 52 U.S.C. § 20501(a).

[67] Id.

[68] Id. The other purposes of the Act are to “(2) to make it possible for Federal, State, and local governments to implement this Act in a manner that enhances the participation of eligible citizens as voters in elections for Federal office; (3) to protect the integrity of the electoral process; and (4) to ensure that accurate and current voter registration rolls are maintained.” Id.

[69] See 52 U.S.C. § 20504.

[70] See 52 U.S.C. § 20505.

[71] See H.R. Conf. Rep. 103-66, at 19 (“If a State does not include either public assistance, agencies serving persons with disabilities… it will exclude a segment of its population from those for whom registration will be convenient and readily available–the poor and persons with disabilities who do not have driver’s licenses and will not come into contact with the other principle place to register under this Act.”).

[72] See 52 U.S.C. § 20501(b) (establishing the purposes of the NVRA). Section 7 of the NVRA which creates the Agency System is consolidated in the U.S. Code as 52 U.S.C § 20506.

[73] Id.

[74] See, e.g., Disabled in Action v. Hammons, 202 F.3d 110, 115 (2d Cir. 2000).

[75] Id.

[76] See, e.g., Hammons, 202 F.3d at 124.

[77] Id.

[78] 52 U.S.C. §20506(a)(6).

[79] 52 U.S.C. §20510.

[80] See Williamson, Cataldo, and Write, supra note 4 at 7.

[81] See id. (“During the 1995-1996 election cycle, 27.5 million new registrants were added to voter rolls across the 44 states (and the District of Columbia) covered by the NVRA . . . .”).

[82] See Delk, supra note 6.

[83] Williamson, Cataldo, and Write, supra note 4 at 7.

[84] Id. (Statistics based on 2016 Census data).

[85] Id. (Statistics based on 2016 Census data).

[86] See Desilver, In Past Elections, supra note 2.

[87] Id.

[88] Fabina & Scherer, supra note 12.

[89] Delk, supra note 6 at 155.

[90] Fabina & Scherer, supra note 12.

[91] Drew Desilver, In Past Elections, supra note 2.

[92] Pew Research center, Why Are Millions of Citizens Not Registered to Vote?, (2017) https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2017/06/why-are-millions-of-citizens-not-registered-to-vote.

[93] See Delk, supra note 6 at 155.

[94] Williamson, Cataldo, and Write, supra note 4 at 9.

[95] Id.

[96] See Voting Section Litigation, U.S. Department of Justice, https://www.justice.gov/crt/voting-section-litigation#nvra_cases (Last accessed Aug., 2022)

[97] See Williamson, Cataldo, and Write, supra note 4 at 11.

[98] Id.

[99] Id.

[100] See, e.g., United States v. Louisiana, 196 F. Supp. 3d 612, 670 (M.D. La. 2016).

[101] 52 U.S.C. § 20501(a).

[102] U.S. Department of Justice, supra note 96.

[103] See Delk, supra note 6 at 155.

[104] Id.

[105] Id.

[106] United States v. New York, 700 F. Supp. 2d 186 (N.D.N.Y. 2010).

[107] Id. at 200.

[108] See Arizona v. Inter Tribal Council of Ariz., Inc., 570 U.S. 1, 13 (2013).

[109] Id. at 14.

[110] Id.

[111] United States v. Louisiana, 196 F. Supp. 3d 612 (M.D. La. 2016).

[112] Id. at 657.

[113] Id.

[114] Id. (quoting Foster v. Love, 522 U.S. 67, 69 (1997)).

[115] Williamson, Cataldo, and Write, supra note 4, at 9.

[116] See Delk, supra note 6 at 155.

[117] Nat’l Council of La Raza v. Cegavske, 800 F.3d 1032, 1036 (9th Cir. 2015).

[118] Id.

[119] Gonzalez v. Arizona, 677 F.3d 383, 388 (9th Cir. 2012).

[120] Id.

[121] See Arizona v. Inter Tribal Council of Ariz., Inc., 570 U.S. 1 (2013).

[122] See id.

[123] See Shelby Cty. v. Holder, 570 U.S. 529, 557 (2013).

[124] United States v. Louisiana, 196 F. Supp. 3d 612, 670 (M.D. La. 2016).

[125] 42 U.S.C. § 1437a(d)(6)(A) (emphasis added).

[126] U.S. Department of Justice, Statement of Interest, Scott v. Schedler (2012), https://www.justice.gov/crt/case-document/si-scott-v-schedler (last accessed Aug., 2022).

[127] United States v. Louisiana, 196 F. Supp. 3d 612, 670 (M.D. La. 2016).

[128] Id. at 675; See also United States v. Missouri, 535 F.3d 844 (8th Cir. 2008) (holding that Secretary of State could not refuse to enforce the provisions of the NVRA against local elections agencies).

[129] See Scott v. Schedler, 771 F.3d 831, 833 (5th Cir. 2014).

[130] See Ga. State Conference of the NAACP v. Kemp, 841 F. Supp. 2d 1320, 1324 (N.D. Ga. 2012) (noting that Georgia’s statute implementing the NVRA only designates provision the food stamp; Medicaid; Women, Infants, and Children; and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families programs as VRAs).

[131] Harkless v. Brunner, 545 F.3d 445, 457 (6th Cir. 2008).

[132] Nat’l Coal. for Students with Disabilities Educ. & Legal Def. Fund v. Allen, 152 F.3d 283, 288 (4th Cir. 1998).

[133] United States v. New York, 700 F. Supp. 2d 186 (N.D.N.Y. 2010).

[134] U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, Voting Section Litigation, https://www.justice.gov/crt/voting-section-litigation#nvra_cases (last accessed 8/7/22).

[135] Williamson, Cataldo, and Write, supra note 4 at 11.

[136] U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Increasing Compliance with Section 7 of the National Voter Registration Act, Briefing Report, (2013), at 2. https://www.U.S.C.cr.gov/reports/2016/increasing-compliance-section-7-national-voter-registration-act.

[137] Williamson, Cataldo, and Write, supra note 4 at 9.

[138] Id.

[139] Id.

[140] Id.

[141] Id. at 11.

[142] Id. at 15.

[143] Id. at 14.

[144] Id.

[145] Id. at 11.

[146] Id.

[147] United States v. Louisiana, 196 F. Supp. 3d 612, 670 (M.D. La. 2016).

[148] See, supra Section IV.B.

[149] See Desilver, In Past Elections, supra note 2.

[150] Dalton, Is Citizen Participation Actually Good for Democracy?, Democracy Audit UK (2017) https://www.democraticaudit.com/2017/08/22/is-citizen-participation-actually-good-for-democracy/ (last accessed Aug., 2022)

[151] See Awan, supra note 1 at 1144.

[152] Williamson, Cataldo, and Write, supra note 4 at 9.

[153] See, e.g.,25 Pa.C.S. § 1102 (establishing Public Housing Authorities under Pennsylvania State law).

[154] 52 U.S.C. § 20506(a)(2)(A).

[155]Agency Overview, Philadelphia Housing Authority (2020) http://www.pha.phila.gov/media/189728/pha_fact_sheet_2020_july_10.pdf, (last visited Aug. 1, 2022).

[156] Id.

[157] Id.

[158] Rules and Responsibilities, Philadelphia Housing Authority, http://www.pha.phila.gov/housing/housing-choice-voucher/rules-and-responsibilities.aspx

[159] About PHA, Philadelphia Housing Authority, http://www.pha.phila.gov/aboutpha/about-pha.aspx (last visited Aug. 1, 2022).

[160] Agency Overview, Philadelphia Housing Authority, supra note 155.

[161]Rules and Responsibilities, Philadelphia Housing Authority, http://www.pha.phila.gov/housing/housing-choice-voucher/rules-and-responsibilities.aspx

[162] Hud’s Public Housing Program, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, https://www.hud.gov/topics/rental_assistance/phprog (last visited 8-1-2022)

[163] A Snapshot of HUD-Assisted Households, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/pdredge/pdr-edge-featd-article-061118.html#:~:text=Today%2C%20HUD%20assists%20nearly%205,the%20provision%20of%20public%20housing.

[164]See Resident Characteristics Report, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/public_indian_housing/systems/pic/50058/rcr. (Query the data retrieval tool for specific statistics).

[165] See 52 U.S.C. § 20501(b)(1)–(2).

[166] See 52 U.S.C. § 20510(a) (“The Attorney General may bring a civil action in an appropriate district court for such declaratory or injunctive relief as is necessary to carry out this chapter.”); 52 U.S.C. § 20510(b)(1)-(2) (“A person who is aggrieved by a violation of this chapter may provide written notice of the violation to the chief election official of the State involved. If the violation is not corrected . . . the aggrieved person may bring a civil action in an appropriate district court for declaratory or injunctive relief with respect to the violation.).

[167] 52 U.S.C. § 20506(a)(2).

[168] See 52 U.S.C. § 20502(1)–(5).

[169] 52 U.S.C. § 20506(a)(2).

[170] Delgado v. Galvin, Civil Action No. 12-cv-10872, 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 33476, at *12-13 (D. Mass. Mar. 14, 2014) (quoting Stornawave Fin. Corp. v. Hill (In re Hill), 562 F.3d 29, 32 (1st Cir. 2009)).

[171]Id.; see also La Raza, 800 F.3d at 1035 (holding that “we assume that the legislative purpose is expressed by the ordinary meaning of the words used” (quoting Am. Tobacco Co. v. Patterson, 456 U.S. 63, 68 (1982))).

[172] Project Vote, Inc. v. Kemp, 208 F. Supp. 3d 1320, 1337 (N.D. Ga. 2016).

[173] See, e.g., Nat’l Council of La Raza v. Cegavske, 800 F.3d 1032, 1035 (9th Cir. 2015) (quoting Hartford Underwriters Ins. Co. v. Union Planters Bank, N.A., 530 U.S. 1, 6 (2000)).

[174] See Gonzalez v. Arizona, 677 F.3d 383, 399-400 (9th Cir. 2012).

[175] See Ferrand v. Schedler, No. 11-926, 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 61862, at *28-29 (E.D. La. May 3, 2012) (holding that “this Court finds that the plain meaning of Section 7 is indeterminate. Thus, this Court must turn to the NVRA’s legislative history to resolve any textual ambiguities.”).

[176] Delgado, 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS, at *13(First quoting In re Hill, 562 F.3d 29, 32 (1st Cir. 2009); and second quoting Davis v. Mich. Dept. of Treas., 489 U.S. 803, 809 (1989)) (internal quotations removed).

[177] Valdez v. Squier, 676 F.3d 935, 938 (10th Cir. 2012) (emphasis added).

[178] Id.

[179] Id. at 945

[180] Id.

[181] Id. (quoting Oxford English Dictionary, Online Edition, Sept. 2011); See also Vladez v. Herrera, No. 09-668 JCH/DJS, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 142209, at *18-25 (D.N.M. Dec. 21, 2010) (holding that “[i]f Congress does not explain the specific meaning of a statutory term, the Court should assume that Congress intended the word to be given its ordinary meaning, “which we may discover through the use of dictionaries.” (quoting Biodiversity Legal Found. v. Babbitt, 146 F.3d 1249, 1254 (10th Cir. 1998)).

[182] Id. (emphasis added)

[183] Id. at 946.

[184] Id.

[185] Id. (noting that 52 U.S.C. § 20506(a)(6) provides the exact language for the declination forms and instructions on the use of the checkboxes at issue in this case).

[186] See Project Vote, Inc. v. Kemp, 208 F. Supp. 3d 1320 (N.D. Ga. 2016).

[187] Id. at 1337 (quoting 52 U.S.C. § 20507(i)(1)).

[188] Id.

[189] Id. at 1338–41.

[190] Id. at 1338 (quoting U.S. v. Louisiana, 196 F. Supp. 3d 612, (M.D. La. 2016).

[191] Id. at 1340 (quoting True the Vote v. Hosemann, 43 F. Supp. 3d 693 (S.D. Miss. 2014)).

[192] Id. (quoting 52 U.S.C. § 20501).

[193] Id. at 1341.

[194] Nat’l Coal. for Students with Disabilities Educ. & Legal Def. Fund v. Allen, 152 F.3d 283, 288 (4th Cir. 1998) (quoting 52 U.S.C.S § 20506(a)(2)(B)) (emphasis added).

[195] Id. at 292.

[196] Id. at 289.

[197] Id. (quoting Webster’s II New Riverside University Dictionary 816 (1988)) (emphasis added).

[198] Id.

[199] Id. (quoting Random House Dictionary of the English Language 1844 (2d ed. 1987)) (emphasis added).

[200] Id. at 290.

[201] Id. (quoting 52 U.S.C. §20506(3)(B)).

[202] Id.

[203] Id. at 291.

[204] Id. at 289.

[205] See, e.g.,Ga. State Conference of the NAACP v. Kemp, 841 F. Supp. 2d 1320, 1331–32 (N.D. Ga. 2012) (noting that “[t]he House Conference Report for the NVRA expressed concern that a proposed amendment ‘would permit states to restrict their agency programs and defeat a principal purpose of this Act-to increase the number of eligible citizens who register to vote.’” (quoting H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 103-66 (1993)); Vladez v. Herrera, No. 09-668 JCH/DJS, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 142209, at *18-25 (D.N.M. Dec. 21, 2010) (holding that “[t]he House-Senate Conference Report finalizing the NVRA …explains that the declination form was added to guard against the possibility of coercion of agency clients”).

[206] Nat’l Coal. for Students with Disabilities Educ. & Legal Def. Fund v. Allen, 152 F.3d 283, 288 (4th Cir. 1998) (quoting H.R. Rep. No. 103-9, at 12 (1993)) (citations omitted).

[207] Id.

[208] Disabled in Action v. Hammons, 202 F.3d 110, 124 (2d Cir. 2000).

[209] See also Rosebud Sioux Tribe v. Barnett, No. 5:20-cv-5058, 2022 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 94721, at *25-27 (D.S.D. May 26, 2022) (rejecting summary judgment and remanding for further processing the question of whether the similarity between the benefits provided by Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) and benefits provided by the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) required that the South Dakota Department of Labor and Regulations to be designated as a VRA).

[210] Hannoms, 202 F.3d at 119 (quoting 52 U.S.C. §20506(a)(2)).

[211] Id. at 121.

[212] Id. at 120.

[213] Id. at 123.

[214] Id.

[215] Id.

[216] Id.

[217] Id. at 125 (quoting Railway Labor Executives’ Ass’n v. ICC, 735 F.2d 691 (2d Cir. 1984)).

[218] Id. at 124 (quoting H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 103-66, at 19 (1993), reprinted in 1993 U.S.C.C.A.N. 140, 144.) (emphasis added).

[219] Id. (emphasis added).

[220] Id. at 116, 121, 123

[221] 52 U.S.C.S §20506(a)(2)

[222] 42 U.S.C.S § 1437a(b)(6)(A);

[223] Id.; see also e.g. Act of May. 28, 1937, P.L. 955, No. 265 (establishing public housing agencies under Pennsylvania State law).

[224] Act of May. 28, 1937, P.L. 955, No. 265.

[225] 35 P.S. § 1550 (emphasis added).

[226] 52 U.S.C. § 20506(a)(2) (emphasis added).

[227] Black’s Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019).

[228] Merriam-webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/office

[229] Philadelphia Housing Authority, Agency Overview, http://www.pha.phila.gov/media/189728/pha_fact_sheet_2020_july_10.pdf, (last visited Aug. 1, 2022).

[230] Id.