By Aamy Kuldip (view PDF version)

I. Introduction

Human trafficking is a horrific crime that involves stealing one’s freedom for profit.[1]Victims of human trafficking may be tricked or forced into providing commercial sex or illegal labor, and are often left extremely traumatized.[2] Online communication platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, and Craigslist, enable human trafficking efforts by providing easy access to personal information that can be used by traffickers to profile and recruit potential victims.[3]The internet further facilitates human trafficking on a global scale increasing the scope of advertising, recruitment, coordination, or control.[4]The potential global scope of internet-facilitated human trafficking greatly complicates criminal and civil investigations and makes the coordination of law enforcement efforts extremely challenging due to evidentiary issues.[5] In its annual Federal Human Trafficking Report, the Human Trafficking Institute found that eighty-three percent of active 2020 trafficking cases involved online solicitation.[6] Specifically, fifty-nine percent of victims in active sex trafficking cases and sixty-five percent of underage victims recruited online in 2020 active sex trafficking cases occurred on Facebook.[7] As an example, a seventeen-year-old girl ran away from her home in North Carolina to be with a thirty-two-year-old man whom she met on Facebook.[8]After chatting over Facebook Messenger, he convinced the victim to meet him in person.[9] Afterwards, he took the victim to a hotel, where she was trafficked and transported to Florida along with three other victims.[10]

Comprehensive federal legislation is necessary to help combat internet-facilitated global human trafficking by making online platforms accountable for their failure to protect their users from becoming victims of trafficking and exploitative schemes.[11] In fact, many of the companies mentioned above benefit from hosting trafficking content on their website.[12] Online communication platforms currently claim they receive full immunity from the acts of individuals using their platforms under Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act.[13] Congress enacted legislation named FOSTA-SESTA to address this blanket claim of immunity but prosecutors have had difficulty being using the law due to its confusing language and challenges in gathering evidence online.[14]

The first section of this paper outlines the current state of internet-facilitated trafficking laws and the lack of accountability for online platforms. The second section details the reasons for change and explores the challenges faced in prosecuting under current law and the deficiencies of new law that was designed to address this harm. The final section advocates for federal legislation that administers an affirmative duty of care on online platforms and legislation that views these companies as a distributor of harmful trafficking content instead of a mere host in order to reject the notion of full immunity.

II. Current Law

It is a common misconception that human trafficking does not occur in the United States.[15] Many people believe that trafficking occurs in rural areas or developing countries.[16] However, this is untrue as statistics show that human trafficking is an estimated $9.5 billion industry in the United States alone.[17] Many trafficking hotlines claim that human trafficking can occur everywhere, in many contexts and industries.[18] In 2020, online “recruitment” increased 22 percent.[19] Recruitment is a term used in human trafficking cases to describe methods used by traffickers to exploit individuals into performing certain acts.[20] Examples of recruitment methods include romance, false job advertisements, abduction, sale of persons, or former victim coercion.[21] Notably, the proportion of potential victims recruited through sites such as Facebook and Instagram increased 125 percent in 2020.[22] Specifically, there was a 120 percent increase in reports of recruitment from Facebook and a ninety-five percent increase of reports of recruitment from Instagram.[23] It is important to note these numbers are from reported cases, and crimes such

as these often go unreported; the actual numbers are likely to be much higher.[24] Despite the increase in online trafficking cases, many of these companies have been able to escape liability for their part in facilitating the trafficking. In September 2019, a Facebook employee posted to their internal site about an investigation into a trans-national human trafficking network that used Facebook and its apps to facilitate the sexual exploitation of at least 20 victims.[25]Another internal report distributed in 2020 found that Facebook’s platforms enable all three stages of human trafficking: recruitment, facilitation, and exploitation.[26]

The federal law that keeps companies immune from claims against victims and criminal prosecution is Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act.[27]Section 230 reads, “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.”[28] Many commentators regard this as the most important piece of internet legislation created.[29]Section 230 holds online websites exempt from liability for the acts or words of others using the platform. The immunity created by this law not only allows for harmful content to be posted on the website, but also makes it so that the websites have less incentive to filter posts for the betterment of their users.

Many lawmakers realized that the lack of accountability for online communication platforms directly led to an increase in online trafficking victims. In response, Congress enacted the “Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act” and the “Stop Enabling Sex Trafficking Act” (FOSTA- SESTA).[30] The law was enacted in 2018 and was initially seen as a huge win for disrupting the online commercial sex market.[31] The passage of FOSTA-SESTA was supposed to be monumental for victim rights and its language allows plaintiffs to bring claims against a company that facilitated trafficking if the company benefitted from the trafficking.[32] FOSTA- SESTA received tremendous support in the U.S. House of Representatives and passed almost unanimously passed in the U.S. Senate.[33] The law aimed to clarify that Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act should not provide legal protection to websites that promote or facilitate crimes such as human trafficking.[34] FOSTA-SESTA was seen as a way to combat these horrific crimes because the bill allowed victims of human trafficking to bring civil claims against social media companies under the Trafficking and Violence Protection Act (TVPA).[35]Additionally, Section 3 of FOSTA allowed criminal penalties for those who “promote or facilitate prostitution and sex trafficking through their ownership, management, or operation of online platforms.”[36]This law created liability for corporations that knew or should have known about the exploitation occurring on their platforms.[37]TVPA imposes criminal liability on corporations that acted with “reckless disregard” in allowing the corporation to financially benefit from human trafficking.[38] Many believed that the implementation of FOSTA-SESTA would disrupt the online commercial sex market; however, challenges in prosecution still exist and therefore the law does not provide adequate and timely justice for victims.

III. Reasons for Change

For a number of reasons, FOSTA-SESTA has proven ineffective at addressing online human trafficking. First, prosecutors have been unable to use FOSTA-SESTA successfully due to its confusing language and evidentiary requirements.[39] Second, online platforms are still receiving limited liability for their part in trafficking because of the continuing interpretation of immunity from Section 230.[40] Finally, FOSTA-SESTA has hindered sex workers rights as the law does not create distinctions between legal sex work and illegal trafficking content.[41]Accordingly, it is important to rework the blueprint of FOSTA-SESTA and create an affirmative duty for online communication platforms to review trafficking related content and keep their users safe from engaging in illegal trafficking content. Since FOSTA-SESTA was implemented in 2018, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) has brought charges in only one case under its rules.[42]According to a study released by the U.S.

Government Accountability Office (GAO), the current online commercial sex market heightens challenges for law enforcement and prosecutors, explaining why criminal cases against these platforms has rarely occurred.[43] Specifically, since the implementation of FOSTA-SESTA, gathering tips to investigate and prosecute those who use or control online platforms in trafficking activities has been increasingly difficult.[44] This is due to online platforms being moved overseas and the use of complex payment systems as well as an increase in the use of social media.[45] The GAO also reports that criminal restitution has never been sought and civil damages have not been awarded under Section 3 of FOSTA.[46] The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) officials also told GAO that information gathering is becoming increasingly difficult because social media or messaging platforms are now encrypted, which allows for more anonymity and instant delete features for messaging applications.[47] According to the study conducted by GAO, the evidence needed to prove allegations of online trafficking includes communication documents, incorporation records, and financial transactions to help prove that those who are in charge of online platforms had intent to promote or conceal the trafficking material posted on their platforms.[48]Additionally, prosecutors have found more success in using charges such as money laundering and racketeering to successfully prosecute traffickers and therefore do not feel the need to use the largely untested FOSTA-SESTA.[49]

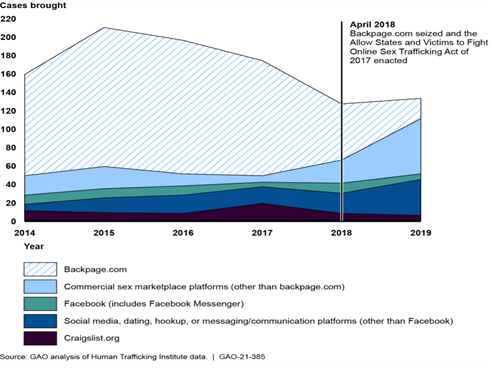

The above figure shows the slow rise in the use of online platforms to solicit buyers of human sex trafficking. Backpage.com, the largest online platform for buying and selling sex, was seized five days before the implementation of FOSTA-SESTA.[50] This was possible because state attorneys general pursued criminal cases against Backpage.com through money laundering charges.[51] However, in July 2020, the Polaris Report, an anti-human trafficking organization, reported that since backpage.com was seized, there has been competition among platforms for the commercial sex market share.[52] The DOJ has confirmed this movement as well.[53]

Two important cases in realizing the importance for changed legislation include Doe v. Twitter and Doe v. Facebook. In Doe v. Facebook, plaintiff Jane Doe was sex trafficked as a minor and Facebook connected her to her trafficker.[54] After being rescued by law enforcement, she brought a claim against Facebook to hold it accountable for its part in her trafficking.[55] Facebook claimed that its platform is immune from any such suit because of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.[56] This provision establishes that websites are not the speaker of information posted and are instead content providers.[57] In this case, the Texas Supreme Court gave publisher immunity to Facebook even though Facebook allegedly knows that its system facilitates human traffickers in identifying and cultivating victims.[58] The court went further to state that the immunity afforded by online platforms should be left to Congress to clarify or under a more appropriate case.[59] Accordingly, Doe v. Facebook illustrates the problem with providing broad immunity to online communication platforms.

In Doe v. Twitter, FOSTA-SESTA was used in the decision, but may also result in mixed results in terms of how online platforms will act in the future.[60] In Doe v. Twitter, the anonymous plaintiffs brought suit on the grounds that they were manipulated into making pornographic videos of themselves.[61] The videos were then posted to Twitter and when plaintiffs asked Twitter to take down the posts, it refused.[62] Here, plaintiffs argue that Twitter violated the law because it knew about and benefitted from the videos and did nothing to fix the problem.[63] Twitter argues that FOSTA-SESTA only narrowly applies to websites that knowingly assisted and therefore “affirmatively participate” in such crimes.[64] Essentially, Twitter argues that the company cannot be held liable just because it did not take down the video.[65] The court eventually said that plaintiffs successfully alleged that Twitter participated in the sex trafficking by not taking down the video in response to takedown notices and the claim survived a motion to dismiss. Though this is a win for the victims, experts say that this result will lead to a notice-takedown measure in which websites will wait to take down sexual content until they receive notice instead of being more proactive and not distributing harmful content in the first place.[66]

Moreover, FOSTA-SESTA’s language is still at odds with the “websites as hosts/publishers” theory in which the website is only liable if it benefits from the trafficking content.[67] Though under this beneficiary theory a case will be likely to survive a motion to dismiss, it may be difficult in gathering evidence and still allows users of these websites to be exposed to harmful trafficking content which can then lead to the recruitment of more victims. In fact, Facebook has said that when problematic posts occur, they address the problem by taking down the posts.[68] The website has not fixed the system that allows these posts to surface to users in the first place and will continue to leave users vulnerable without fixing its systems.[69]

Finally, the way FOSTA-SESTA is written currently incentivizes companies to remove any content related to sexual content, even if it is consensual and used to promote the work of sex workers.[70] When first passed, sex workers claimed their safety would be at risk since they relied on the online communication platforms to work and keep themselves safe from others controlling their work.[71] Sex workers use online communication platforms to information share with others about health resources, safe clients, and harm-reduction techniques.[72] When FOSTA-SESTA was passed, it triggered websites to take down any posts that were related to sexual content in fear of being held liable for hosting trafficking content.[73] These concerns are even more justifiable as online human trafficking cases have increased since the implementation of FOSTA-SESTA.[74]

IV. The Proposal

FOSTA-SESTA provides an initial blueprint for dealing with online platforms that host and benefit from trafficking content. Although the purpose of FOSTA-SESTA was sound, the structure and language of the law was insufficient to meet the needs of prosecutors and victims. As written, FOSTA-SESTA aims to clarify that Section 230 was never intended to “provide legal protection websites that unlawfully promote and facilitate prostitution and websites that facilitate traffickers in advertising the sale of unlawful sex acts with sex trafficking victims.”[75] However, as described in the cases against online platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, communication platforms continue to claim immunity from liability under Section 230.[76] In the alternative, the enforcement of FOSTA-SESTA will result in taking down posts that would otherwise lead to consensual sex work.

Instead of using FOSTA-SESTA’s language of requiring the corporation benefiting from the trafficking content to be held liable, an exception should be created in which Section 230’s immunity should not be applied in cases where the online platform fails to protect their users from illegal trafficking content. Other businesses that also benefit from trafficking operations, such as hotels and airlines, are required to take reasonable measures to prevent these crimes.[77] However, Section 230 prevents such reasonable measures from being applied to online platforms.[78]The beneficiary theory also makes evidence gathering difficult for prosecutors and victims and hinders access to justice for many taken advantage of online.

In order to address these deficiencies, new federal legislation is required to expressly carve out an exception for Section 230, as well as amend FOSTA-SESTA to implement a standard of care that would hold online communication platforms liable if they did not take reasonable steps to protect their users from harmful trafficking content. Specifically, Section 230 would be amended to create an exception for immunity for websites that have an algorithm in place that distributes posts to users. FOSTA-SESTA would be amended to impose a standard of care for online platforms to take reasonable steps to protect users from illegal trafficking content.

As asserted in the Doe v. Twitter complaint, online communication platforms are not a mere host of content.[79] They instead use algorithms and other technological devices to make sure their user’s posts are seen by others.[80] “Twitter is not a passive, inactive, intermediary in the distribution of this harmful material; rather, Twitter has adopted an active role in the dissemination and knowing promotion and distribution of this harmful material.”[81] This language is specifically references Twitter’s business model and technological architecture.[82] By the nature of algorithms, social media and online websites “take the reins” in determining which content is delivered to their users based on past behavior and interactions.[83]

An algorithm is defined as a mathematical set of rules that specifies how a group of data behaves.[84] Usually, the purpose of an algorithm is too filter content to the user’s liking and suggest videos or posts that the user is likely to engage in.[85] However, an analysis of the social media site “YouTube” found that 64 percent of users came across videos on the platform that seemed false or untrue.[86] Additionally, 60 percent of users encountered videos of people engaging in dangerous or troubling behavior.[87]Essentially, social media and online communication platforms have some hand in determining which posts or content a user sees and engages with.[88] The website distributes content to users as the algorithm sees fit and therefore can play a part in facilitating trafficking efforts as the algorithm will purposefully aim to have the harmful posts be seen by users likely to interact with the post. As shown in Doe v. Twitter, the video of the two minor boys engaged in sexual acts was distributed to many viewers and users because of the platform’s algorithm amplification.[89] Further, some online communication platforms have messaging platforms that connect its users to other users. This messaging platform should be seen as information distributing as users are connected to others by the algorithm determining who one may want to chat with through their platforms.

Therefore, new legislation is required to carve out an exception for immunity for Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act for websites that distribute harmful trafficking content. As mentioned before, the current Section 230 exception under FOSTA-SESTA is for websites that benefit from facilitating trafficking content.[90] This new distributer model will increase access to justice for victims because victims and prosecutors will not need to produce affirmative evidence that a website benefitted from the content. Instead, the websites will be held liable if their algorithms were found to distribute harmful trafficking posts and therefore lead to individuals being trafficked through their website. Websites will then be held accountable for the way they amplify content, especially content that causes users to become trafficking victims. Though the website itself may not create the harmful content, it plays a significant role in distributing the harmful information to other users and allows users to further engage with the post, thereby increasing the likelihood of other potential victims seeing the post. For example, if a website’s algorithm allows for users to come across recruitment posts or messages, the website will be held legally liable for any impacts.[91] The second part of the new legislation would impose a standard of care that heightens the duty of online communication platforms that protects users from interacting with trafficking content rather than having websites take down harmful posts after receiving notice of these posts and blocking potential posts by consensual sex workers. This language would be amended in FOSTA-SESTA’s current language, as FOSTA-SESTA will continue to serve as a blueprint for new legislation. Currently, FOSTA-SESTA’s language allows for a reckless disregard standard of care for online trafficking.[92] The proposed change in language will require these businesses and corporations to take reasonable steps to prevent facilitating online trafficking activities.[93] The reasonable steps requirement will be akin to what is required of hotel and airline industries in their efforts to stop enabling trafficking efforts.[94]

Reasonable steps may include employing an independent oversight organization or agency that would review trafficking or sex work related posts before they are distributed among other users among the online platform. Many of the companies mentioned already conduct internal reviews of harmful content that may disrupt their platform.[95] For example, Facebook’s internal report noted that a gap exists in detection of entities on the platform engaging in domestic servitude and labor trafficking.[96] The website also had internal documents included in disclosures given to Congress by a former employee.[97] These reports and documents included information about human trafficking content on Facebook’s applications and research into their algorithm promoting other harmful content.[98]

The existence of these reports shows that since companies may already conduct internal reviews of such content, they have the capabilities to take further steps to ensure their users are not given the opportunity to engage with potentially harmful content while allowing consensual sex work to take place. The independent oversight agency may also report its findings to the company’s stakeholders in order to ensure full accountability.

Online platforms may argue that paying for moderators and reviewers could be expensive.[99] Though this may not be an issue for the largest online communication platforms, smaller companies may not have the resources to police their content.[100] Congress could likely lend their support to the proposed changes to Section 230 as many Republicans and Democrats have expressed their frustration with the law.[101] Republicans argue that technology companies censor certain political posts and receive immunity from Section 230 and Democrats assert that big tech is “taking advantage” of the freedom provided to them.[102] As there is agreement that Section 230 has provided online communication platforms with too much power, Congress may support the proposed exception that would view websites that facilitate harmful content to be distributors and therefore not immune from civil or criminal claims.

V. Conclusion

To conclude, online communication platforms continue to escape liability for their part in facilitating human trafficking and exposing their users’ harmful content. Though FOSTA- SESTA was a step in the right direction intended to keep these websites and companies liable, it unfortunately did not have it intended effect. Section 230 still allows for online communication platforms to claim immunity when confronted with civil suits from victims. This proposal would carve out an exception for immunity when a website distributes harmful trafficking posts to their users. Additionally, new federal legislation will make it so websites will have an increased standard of care to take affirmative steps to protect their users from being exposed to trafficking content. This will ideally be conducted by and independent agency that will allow for consensual sex work to be conducted without the fear of increasing online trafficking recruitment.

VI. Appendix

The proposed change in legislation to Section 230 (47 U.S.C § 230) would read:

“No provider user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the speaker of any information, but may be treated as a distributor of information provided by another information content provider if the interactive computer service uses algorithms or other methods to connect users to such content”

The proposed amendment to FOSTA-SESTA, specifically Section 3(b)[103] would read:

“Whoever, using a facility or means of interstate or foreign commerce or in affecting interstate or foreign commerce, owns, manages, or operates an interactive computer service, or conspires or attempts to do so, with the intent to promote or facilitate the prostitution of another person and (1) fails to take reasonable measures to prevent conduct contributing to online sex and labor trafficking”

[1] What is Human Trafficking?, NAT’L HUMAN TRAFFICKING HOTLINE, https://humantraffickinghotline.org/what- human-trafficking (last visited Aug. 9, 2022).

[2] Id.

[3] Good Use and Abuse: The Role of Technology in Human Trafficking, United Nations Office on DRUGS AND CRIME (Oct. 14, 2021), https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/human-trafficking/Webstories2021/the-role- of-technology-in-human-trafficking.html.

[4] Alyssa Currier Wheeler, Sex Traffickers Are Increasingly Turning to Social Media for Victim Recruitment, MARKETPLACE TECH (Jan. 31, 2022), https://www.marketplace.org/shows/marketplace-tech/sex-traffickers-are-increasingly-turningto-social-media-for- victim-recruitment/.

[5] Law and Crime Prevention, Traffickers Abusing Online Technology, UNITED NATIONS (Oct. 31, 2021), https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/10/1104392.

[6] How Sex Traffickers Use Social Media to Find, Groom, and Control Victims, FIGHT THE NEW DRUG (July 20, 2021), https://fightthenewdrug.org/how-sex-traffickers-use-social-media-to-findgroom-and-control-victims/.

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] Id.

[10] Id.

[11] See generally January Contreras & Katherine Chon, Technology’s Complicated Relationship with Human Trafficking, ADMIN. FOR CHILDREN & FAMILIES (July 28, 2022), https://www.acf.hhs.gov/blog/2022/07/technologys-complicated-relationship-human-trafficking.

[12] Id.

[13] Quinta Jurecic, The Politics of Section 230 Reform: Learning from FOSTA’s Mistakes, BROOKINGS (Mar. 1, 2022), https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-politics-of-section-230reform-learning-from-fostas-mistakes/.

[14] Jill Steinberg & Kelly M. McGlynn, Trafficking and Child Exploitation Online: The Growing Responsibilities of Entities Operating Online Platforms, BALLARD SPAHR (Mar. 7, 2022), https://www.ballardspahr.com/insights/alerts- and-articles/2022/03/trafficking-and-childexploitation-online-the-growing-responsibilities-of-entities-operating- online.

[15] Misconceptions, Greater New Orleans Human Trafficking Task Force, http://www.nolatrafficking.org/myths-and-misconceptions (last visited Aug. 9, 2022).

[16] Id.

[17] Id.

[18] Id.

[19] Analysis of 2020 National Human Trafficking Hotline Data, POLARIS, https://polarisproject.org/2020-us-national-human-trafficking-hotline-statistics/ (last visited Aug. 9, 2022).

[20] Id.

[21] Id.

[22] Id.

[23] Id.

[24] Id.

[25] Clare Duffy, Facebook has Known it has a Human Trafficking Problem for Years. It Still Hasn’t Fully Fixed It, CNN BUSINESS (Oct. 25, 2021), https://www.cnn.com/2021/10/25/tech/facebookinstagram-app-store-ban-human- trafficking/index.html.

[26] Elizabeth Elkind, Over Half of Online Recruitment in Active Sex Trafficking Cases Last Year Occurred on Facebook, Report Says, CBS NEWS (Jun. 10, 2021), https://www.cbsnews.com/news/facebook-sex- trafficking-online-recruitment-report/.

[27] See generally, CDA 230 The Most Important Law Protecting Internet Speech, ELECTRONIC FRONTIER FOUND., https://www.eff.org/issues/cda230 (last visited Aug. 9, 2022).

[28] 47 U.S.C. § 230.

[29] Amelia Gallay, Sex Sells, But Not Online: Tracing the Consequences of FOSTA-SESTA, BERKELEY JOURNAL OF

CRIMINAL LAW (Dec. 4, 2021), https://www.bjcl.org/blog/sex-sells-but-notonline-tracing-the-consequences-of- fosta-sesta.

[30] Id.

[31] Id.

[32] Id.

[33] William M. Sullivan, Jr. & Fabio Leonardi, Bill Expands Corporate Liability For Human Trafficking to Social Media Companies, PILLSBURY (Mar. 27, 2018), https://www.pillsburylaw.com/en/news-and-insights/bill-expands-corporate-liability-for humantrafficking-to-social- media-companies.html.

[34] William M. Sullivan, Jr. & Fabio Leonardi, Prosecuting Corporations that Benefit Financially from Human Trafficking, PILLSBURY (July 24, 2019), https://www.pillsburylaw.com/en/news-andinsights/prosecuting- corporations-that-benefit-financially-from-human-trafficking.html.

[35] Id.

[36] U.S. Accountability Office, GAO-21-385, Sex Trafficking Online Platforms and Federal Prosecutions, (June 2021).

[37] Id.

[38] Id.

[39] Id.

[40] Id.

[41] Liz Tung, FOSTA-SESTA Was Supposed to Thwart Sex Trafficking. Instead, it Sparked a Movement, WHYY (July 10, 2020), https://whyy.org/segments/fosta-sesta-was-supposed-tothwart-sex-trafficking-instead-its-sparked-a- movement/.

[42] Adi Robertson, Internet Sex Trafficking Law FOSTA-SESTA is Almost Never Used, Says Government Report, THE VERGE (June 24, 2021), https://www.theverge.com/2021/6/24/22546984/fosta-sesta-section-230-carveout-gao-reportprosecutions.

[43] U.S. Accountability Office, GAO-21-385, Sex Trafficking Online Platforms and Federal Prosecutions, (June 2021).

[44] Id.

[45] Id.

[46] Id.

[47] Id.

[48] Id.

[49] Opinion, The Pitfalls of an Anti-Sex Trafficking Law Give Congress a Warning, WASH. POST (June 26, 2021, 8:00 AM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/06/26/pitfalls-an-anti-sextrafficking-law-give-congress- warning/.

[50] U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off., GAO-21-385, Sex Trafficking: Online Platforms and Federal Prosecutions 14 (2021).

[51] Id.

[52] Jonathan Greig, FOSTA-SESTA Trafficking Law Used Once Since 2018: GAO Report, ZDNET,

(June 25, 2021), https://www.zdnet.com/article/fosta-sesta-trafficking-law-used-once-since2018-gao-report/

[53] Id.

[54] Doe v. Facebook, Inc., 142 S. Ct. 1087, 1087 (2022).

[55] Id.

[56] Id.

[57] Id.; 47 U.S.C. § 230.

[58] Jill Steinberg & Kelly M. McGlynn, supra note 14.

[59] Clare Morell, The Supreme Court Should Review Section 230’s Interpretation, NEWSWEEK, (Nov. 4, 2021), https://www.newsweek.com/supreme-court-should-review-section-230sinterpretation-opinion-1645193.

[60] Doe v. Twitter, Inc., 555 F. Supp. 889 (N.D. Cal. 2021).

[61] Ahmad Hathout, Judge Rules Exemption Exists in Section 230 for Twitter FOSTA Case, BROADBANDBREAKFAST, (Aug. 24, 2021), https://broadbandbreakfast.com/2021/08/california-judge-rules-exemption-exists-in-section-230for-twitter-fosta- case/.

[62] Id.

[63] Id.

[64] Id.

[65] Id.

[66] Eric Goldman, FOSTA Claim Can Proceed Against Twitter – Doe v. Twitter, TECH & MKTG. L. BLOG, (Sept. 6, 2021), https://blog.ericgoldman.org/archives/2021/09/fostaclaim-can-proceed-against-twitter-doe-v-twitter.htm.

[67] Id.

[68] Justin Scheck et al., Facebook Employees Flag Drug Cartels and Human Traffickers. The Company’s Response Is Weak, Documents Show., WALL ST. J., (Sept. 16, 2021), https://www.wsj.com/articles/facebook-drug-cartels-human-traffickers-response-is-weakdocuments-11631812953.

[69] Id.

[70] Liz Tung, supra note 38.

[71] Daisy Soderberg-Rivkin, The Lessons of FOSTA-SESTA from a Former Content Moderator, R ST., (Apr. 8, 2020), https://www.rstreet.org/2020/04/08/the-lessons-of-fosta-sesta-from-aformer-content-moderator/.

[72] Id.

[73] Id.

[74] Id.

[75] Jeffrey Neuburger, FOSTA Signed into Law, Amends CDA Section 230 to Allow Enforcement against Online Providers for Knowingly Facilitating Sex Trafficking, PROSKAUER: NEW MEDIA & TECH. L. BLOG, (Apr. 11, 2018), https://newmedialaw.proskauer.com/2018/04/11/fosta-signed-into-law-amendscda- section-230-to-allow-enforcement-against-online-providers-for-knowingly-facilitating-sextrafficking/.

[76] Doe v. Twitter, Inc., 555 F. Supp. 889 (N.D. Cal. 2021); Doe v. Facebook, Inc., 142 S. Ct. 1087 (2022).

[77] See generally, Meghan Poole, Beyond Hospitality: Hotel Liability for Trafficking, HUM. TRAFFICKING INST., (Jan. 24, 2019), https://traffickinginstitute.org/beyond-hospitality-hotelliability-for-trafficking/

[78] Id.

[79] Complaint at 5, Doe v. Twitter Inc., 555 F. Supp. 3d (N.D. Cal. 2021).

[80] Id. at 8.

[81] Id. at 3.

[82] Id.

[83] Brent Barnhart, Everything You Need to Know About Social Media Algorithms, SPROUT SOC. BLOG, (Mar. 26, 2021), https://sproutsocial.com/insights/social-media-algorithms/.

[84] Clodagh O’Brien, How Do Social Media Algorithms Work?, DIGIT. MKTG. INST.: DIGIT. MKTG. BLOG, (Jan. 19, 2022), https://digitalmarketinginstitute.com/blog/how-do-social-media-algorithms-work.

[85] Id.

[86] Id.

[87] Id.

[88] Editorial Board, Social media algorithms determine what we see. But we can’t see them., THE WASHINGTON POST, (Feb 3, 2023), https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/08/09/social-media-algorithms-determine- what-we-see-we-cant-see-them/

[89] Doe v. Twitter, Inc., 555 F. Supp. 889 (N.D. Cal. 2021).

[90] Quinta Jurecic, supra note 10.

[91] Charles Matula, Any Safe Harbor in a Storm: SESTA-FOSTA And the Future of § 230 Of the Communications Decency Act, 18, DUKE L.J., 353, 368 (2020).

[92] U.S. GOV’T ACCOUNTABILITY OFF., supra note 48.

[93] Jill Steinberg and Kelly M. McGlynn, supra note 11.

[94] Jordi Lippe-McGraw, What the travel industry is doing to prevent human trafficking – and how you can help, THE POINTS GUY, (Feb. 3, 2023), https://thepointsguy.com/guide/travel-industry-human-trafficking/

[95] Angel Diaz and Laura Hecht-Felella, Double Standards in Social Media Content Moderation, BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE, (Feb. 3, 2023), https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/double- standards-social-media-content-moderation

[96] Duffy, supra note 25.

[97] Id.

[98] Id.

[99] Matula, supra note 90, at 360.

[100] Id.

[101] Id. at 366.

[102] Id. at 367.

[103] H.R.1865 — 115th Congress (2017-2018).