When I looked at the article titles for our readings this week, I have to admit that I was at first glance, a bit unenthusiastic. Most of the titles had something to do with furniture and dining, both topics that I would not identify with or be overly excited to study. Fortunately, reading these articles afforded me the opportunity to think about objects beyond their face value. For me personally, it is not the physical piece of furniture that holds value, but rather the historical or cultural context that can be gained from it. By the end of the week, I realized that I am often quick to write things off because they do not initially grab my intention. However, I now acknowledge that it is important to explore the context beyond the object in order to gain a better understanding about history.

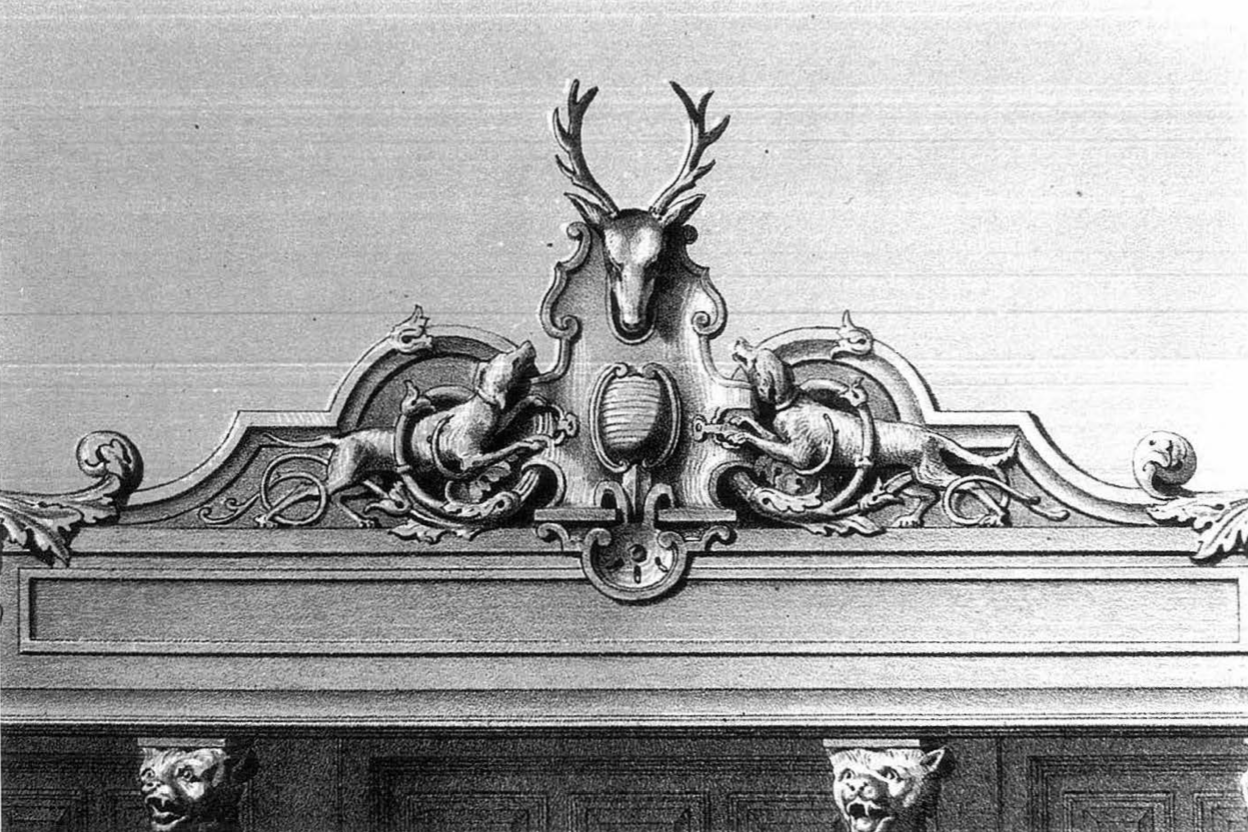

I started off by reading Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s article, “Furniture as Social History.” In this piece, Ulrich makes a connection between furniture and understanding historical trends and ideas about gender, family, and property in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Ulrich compares pieces of furniture to portraits of men and women to reveal societal ideas on gender according to similarities in make and style. The next article I read was “Death in the Dining Room” by Kenneth Ames. In this piece, Ames looks at trends in Victorian Era furniture that seem strange and slightly disturbing my us today. Specifically, he talks about the iconography of dead animals carved onto dining room furniture along with other representations of fruits, vegetables, grains, and nuts. Ames uses these distinct Victorian pieces to get readers to question the significance of them to the people of the time. There are several different ways to interpret these pieces. The dead animals such as deer and fish could represent the achievement of a hunt and bountiful harvest. The lavish carvings themselves could be a status symbol for the wealthy elite.

Next, I read “The Furniture of Thomas Day: A Reevaluation” by Johnathan Prown. In this piece, Prown writes about Thomas Day, a furniture maker who was also a free person of color in North Carolina. Those who study Day’s work are interested in the inspiration for his unique designs. Though some would rush to say that Day was inspired by blending of West African and Euro-American art, Prown encourages interpretive caution and reevaluation. Prown argues that Thomas Day and his work are, “complex entities that straddle a wide range of racial, social, and artistic lines” and that the term, “African American” is not a monolithic cultural identity. In conclusion, this article was not about furniture, as I first thought it would be, but rather about the ethnic identity of a biracial businessman in the antebellum south.

The final article I read for this week was Dayna M. Pilgrim’s, Master’s of a Craft: Philadelphia’s Black Public Waiters, 1820-50. In this piece Pilgrim explores the history of Philadelphian dining rooms, not necessarily by looking at specific pieces of furniture, but by looking at the experience of fine dining at the time. In exploring this, we find out that black public waiters, or caterers played an important role in the dining experience. Furthermore, Pilgrim argues that dining rooms not only transformed the lives of public waiters, but were also transformed by them. Instead of using dining rooms to study the culture and power dynamics of the bourgeouisee, Pilgrim restores agency to the black public waiters by explaining how people of African descent used and transformed the dining experience to their advantage.