By Lauren Griffin, Public History MA student at Temple University

The first generation of students that attended Temple sourced their meals from a variety of different places. Some students commuted from home, some sought out meals at diners and lunch shops, or some students ate their meals at their nearby boarding houses. One of the early restaurants near campus was the Temple Restaurant, a lunch shop that was in operation until at least 1911. In 1908, they even served supper for students attending night classes. At this time, men and women had to dine in separate rooms.

The Temple Restaurant was the first instance of university dining. The Great Depression interrupted the growth of Temple, but the administration responded by offering financial aid and by expanding services available to students. In the 1920s and 1930s with enrollment recovering after World War I and the Depression, Temple began constructing its own buildings near the Baptist Temple. One of those buildings was Mitten Hall, which permanently changed the campus environment as a student activities center. Not only a space for students to host club meetings and study sessions, it also offered a brand new cafeteria space.

In addition, Temple started building dorms for students to live on campus. The construction projects in the 1930s under Temple President Charles Beury marked the beginning of Temple’s significant expansion into the surrounding neighborhood. Temple transformed from a university of row houses and commuters into a more idealized version of a university campus. Those row homes were not empty, however, and it was during this time period that Temple began demolishing the homes of its neighbors and erasing the former history of North Broad Street.

For students and faculty, life on campus was good for a while. Mitten Hall was the center of student life. The cafeteria, dubbed ‘Casa Grilla,” hosted theatrical performances, poetry readings, dances, and special dinners. Things would change in the 1940s, however, when World War II came to campus. Students were drafted and left the university to fight overseas, and educational programming was modified to better assist a country at war. The US government also established a rationing system and in 1942 began restricting the quantity of high-demand food items that individuals could purchase. The annual Founder’s Dinner celebrating the legacy of Russell Conwell was even canceled one year due to rationing. While individuals were encouraged to plant victory gardens and start canning their vegetables, Temple’s student dining facilities struggled.

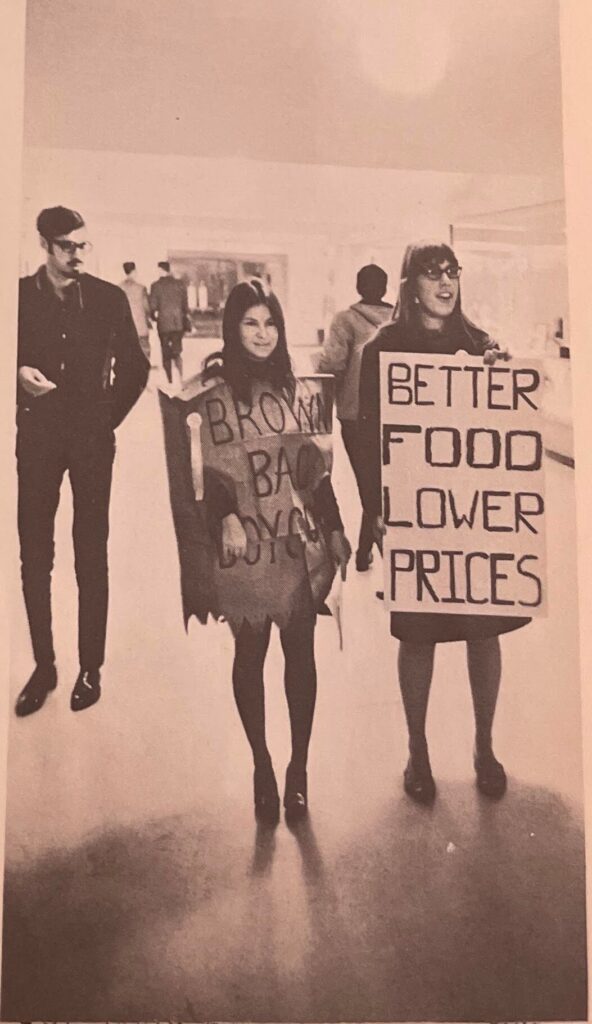

After World War II ended, enrollment at Temple once again surged as veterans returned home and used their GI Bills to go to college. Temple expanded and built more dormitories and student dining facilities. Since the 1930s, the meals at Temple dining halls were prepared by Slater Food Company. Founded by Philadelphian John F. Slater, the company specialized in corporate and university cafeterias that focused on feeding large groups of people as quickly as possible. The relationship between Slater Food Service and the students of Temple was tenuous. In the 1970s, it came to a head with the Brown Bag Boycott.

Starting in the 1960s, students expressed their frustrations with how dining halls were managed. Cafeteria “bouncers” would kick students out of the dining room if they weren’t actively eating, food prices fluctuated randomly, and students regularly complained that dishware was dirty and servers got their orders wrong. The Dorm Senate Food Committee met to try and figure out a solution to students’ concerns, but Slater services also had complaints. Slater claimed that they had to devote a significant amount of their budget to replacing stolen dishware, coffee pots, and utensils. If students would stop stealing, Slater pledged to serve sirloin steaks and lobster in the dining halls. The cafeteria bouncer was actually an employee of the university in place to keep the student areas under control, and the dining halls had been notoriously overcrowded for years.

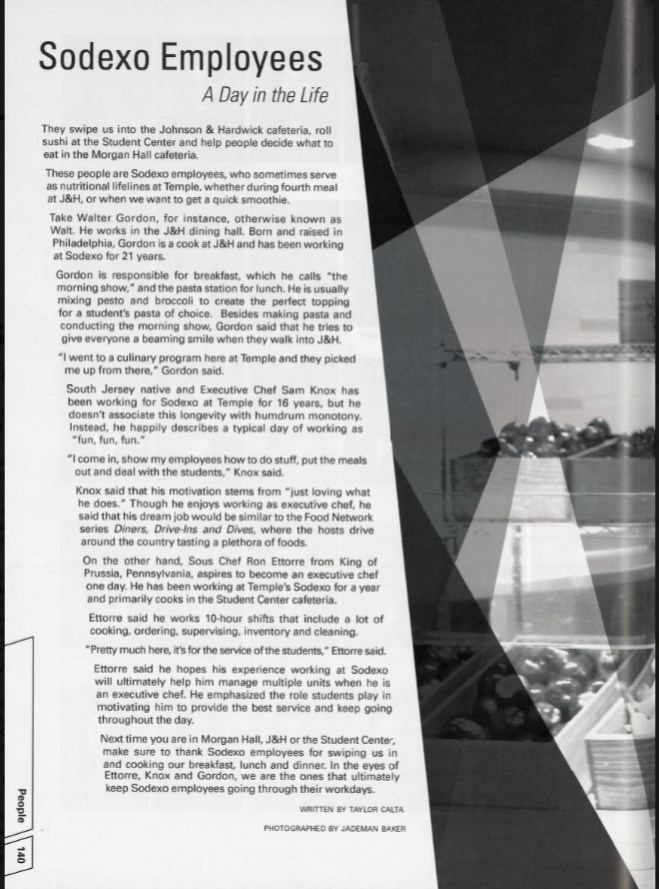

In 1968, students had finally had enough. The Brown Bag Boycott Committee instituted a full boycott of Temple dining halls and Slater Food Services and encouraged all Temple faculty and students to bring bagged lunches from home. The catalyst this time around was Slater raising the price of a cup of coffee from 10 cents to 12 cents. This might seem minor, but Slater had been gradually increasing food prices over the past decades. The radicals behind the boycott were successful – prices were lowered. This wasn’t the end of Temple’s relationship with corporate food services, however. Slater would be replaced with Sodexo, and in 2017 the Sodexo contract was replaced with Aramark Food Services.

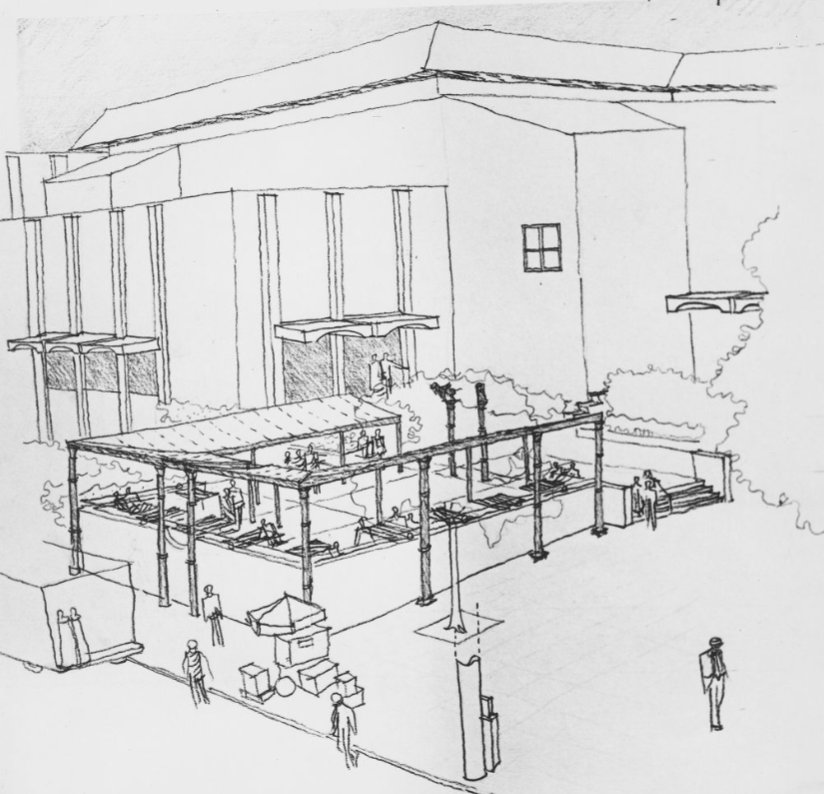

By the 1970s, Temple and its students had outgrown Mitten Hall. They needed a new space for the growing student population, so they built the Student Activities Center (the SAC) in 1971. The SAC continues to be a hub for student life on campus, offering expansive cafeteria and dining space, offices for student services, entertainment options, a bookstore, and more. It’s been renovated and expanded since the 1970s to continue to meet the needs of the shifting student population.

Even though Mitten Hall is no longer the center of student life on campus, it holds a special place in Temple University’s history as a space of community, protest, and development. Students struggled against the corporatization of their meals, but there was a new answer to this problem: food trucks.