By Lauren Griffin, Public History MA student at Temple University

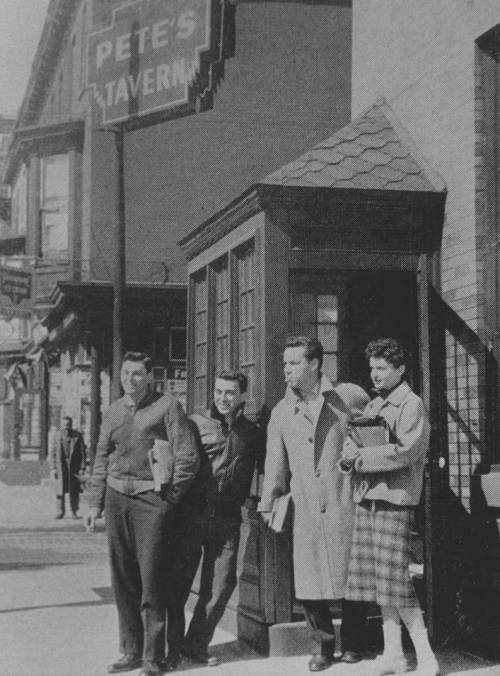

Seeing food trucks and carts along a city street is not an uncommon sight. As you walk around Temple’s campus, however, you might notice that there are a few more food trucks than normal. Some of them don’t even really look like food trucks. There’s little stalls, a shipping container, metal carts, mobile trucks, and immobile trucks hardwired into the infrastructure of the street. For the Temple community, these trucks are beloved. During lunchtime, students crowd the windows, placing orders for birria tacos, Japanese teppanyaki, hoagies, and more. Although it might be surprising for something that seems so integral to Temple’s culture as an urban university, the food trucks and their operators had to fight to be there. So, what is the relationship between Temple and the trucks, and where did it start?

Street vendors were common in Philadelphia beginning in the 1800s, but because of their transient nature it can be challenging to pin evidence of their presence. It’s possible that the first street vendor at Temple was the young Walter Johnson, selling the classic Philadelphia food item, pretzels, in 1924.

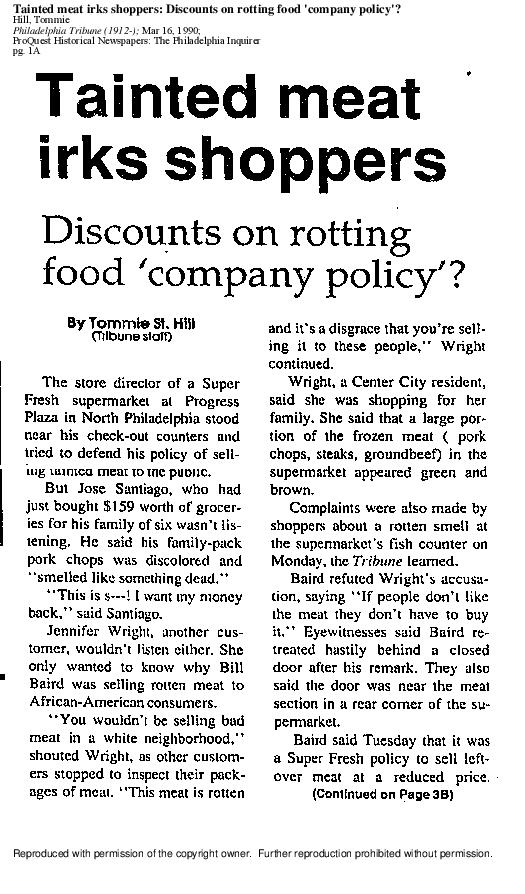

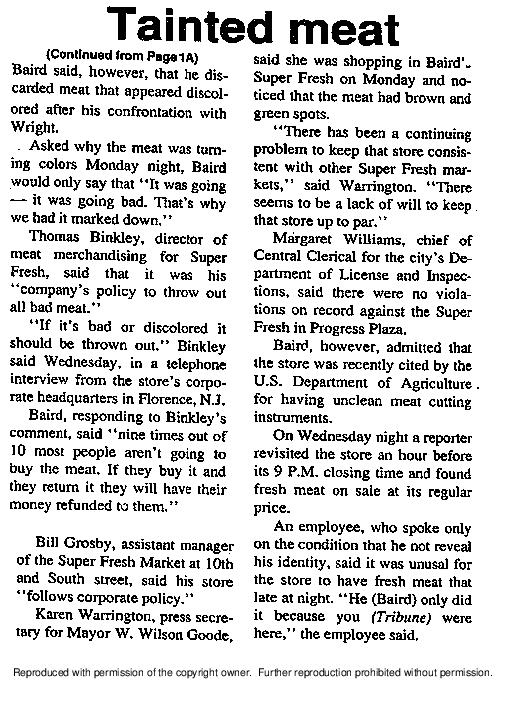

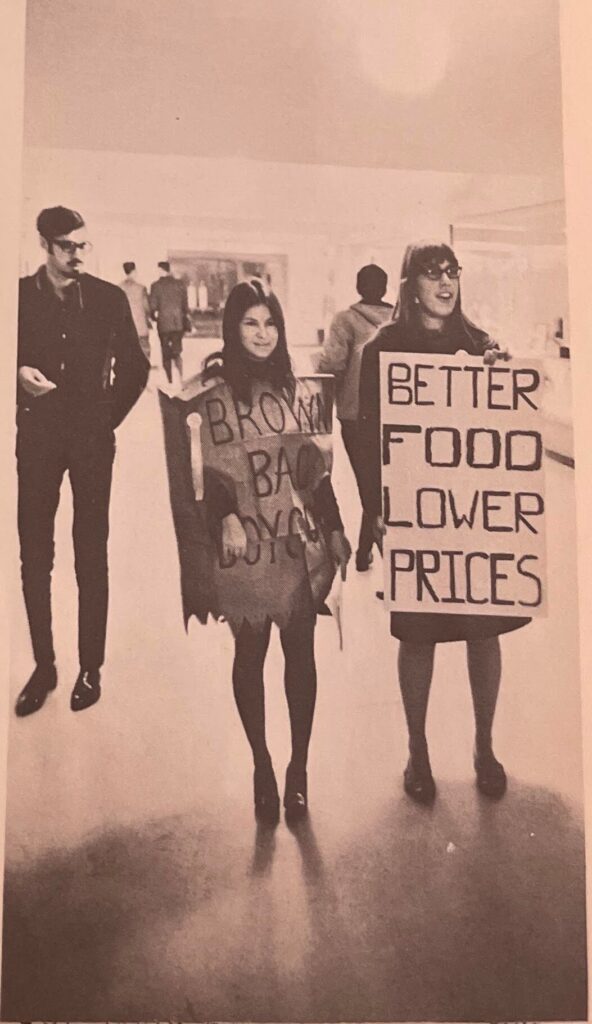

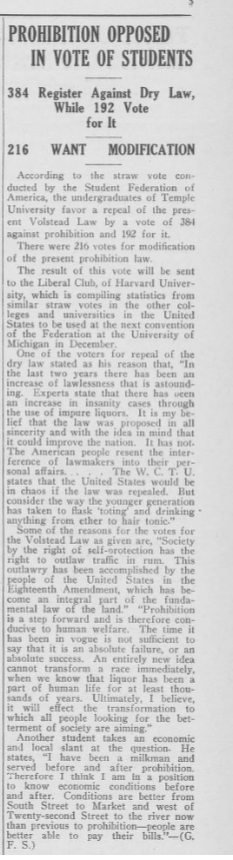

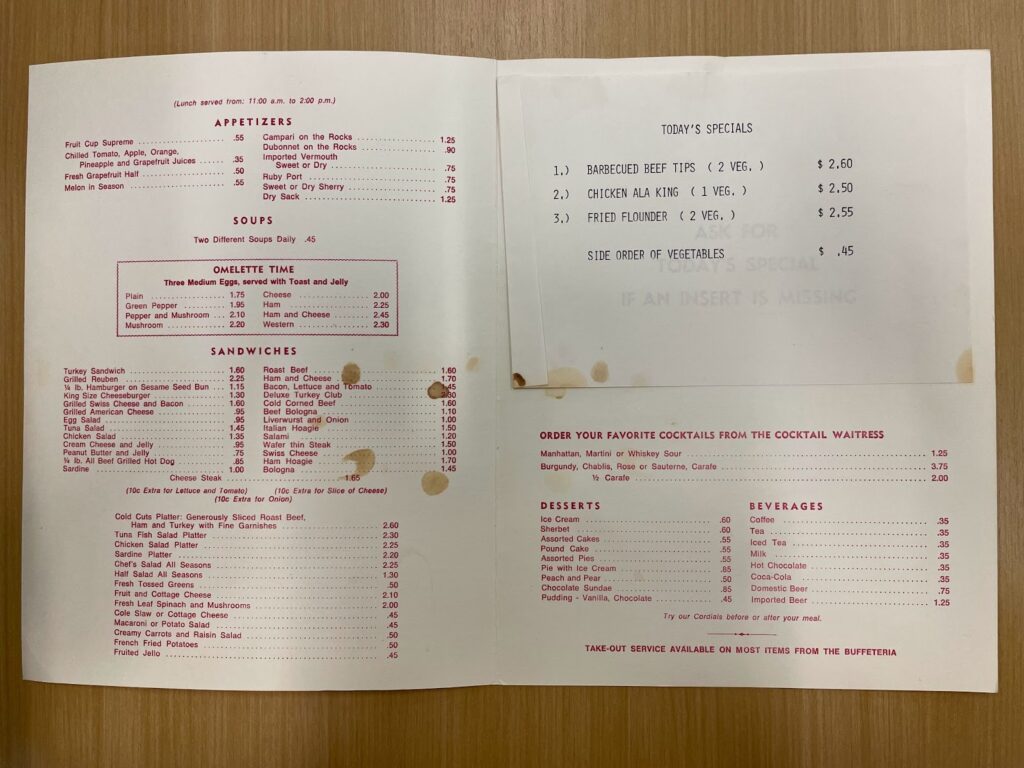

Another early food vendor on campus was William “Bill” Bush. Like Johnson, Bush sold pretzels. He also sold ice cream, candy, and apples right in front of College Hall for over a decade. In the 1940s, the city of Philadelphia introduced new sanitation regulations and a system of licensing for street vendors. After adjusting to the new regulations and in response to the growing student population and campus in North Philadelphia, street vendors started clustering around Temple University in larger numbers in the 1960s. Students were increasingly dissatisfied with university food offerings, and the food trucks filled a need for affordable, delicious, and quick food.

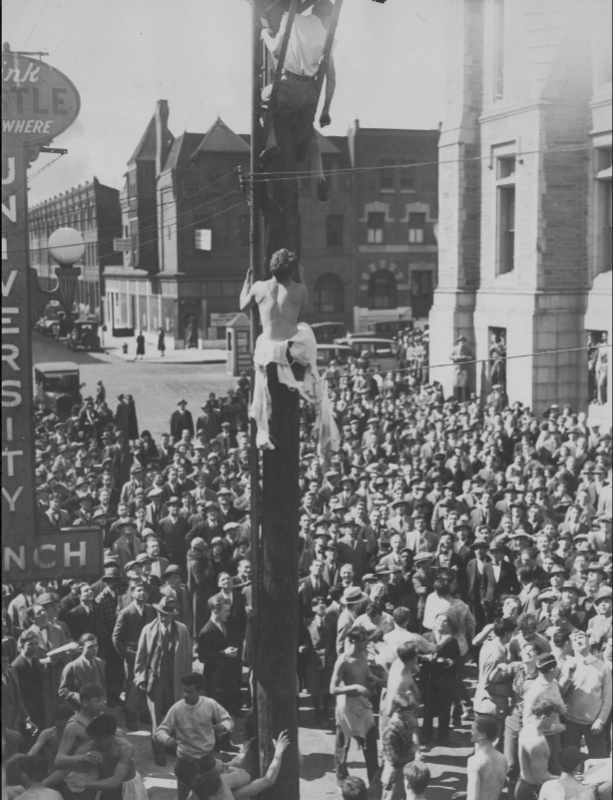

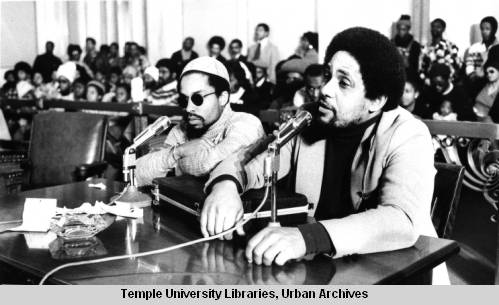

One of the most famous and influential vendors of this time were two brothers, John and Milton Street. The Street brothers started out selling hot dogs and cheesesteaks on campus, but both would go on to become major figures in Philadelphia politics. John Street was mayor of Philadelphia for two terms, and Milton was an activist that fought for affordable housing before turning his attention to public office. Milton Street rose to prominence on Temple’s campus when he began speaking out against discriminatory practices by Temple University that targeted Black vendors on campus.

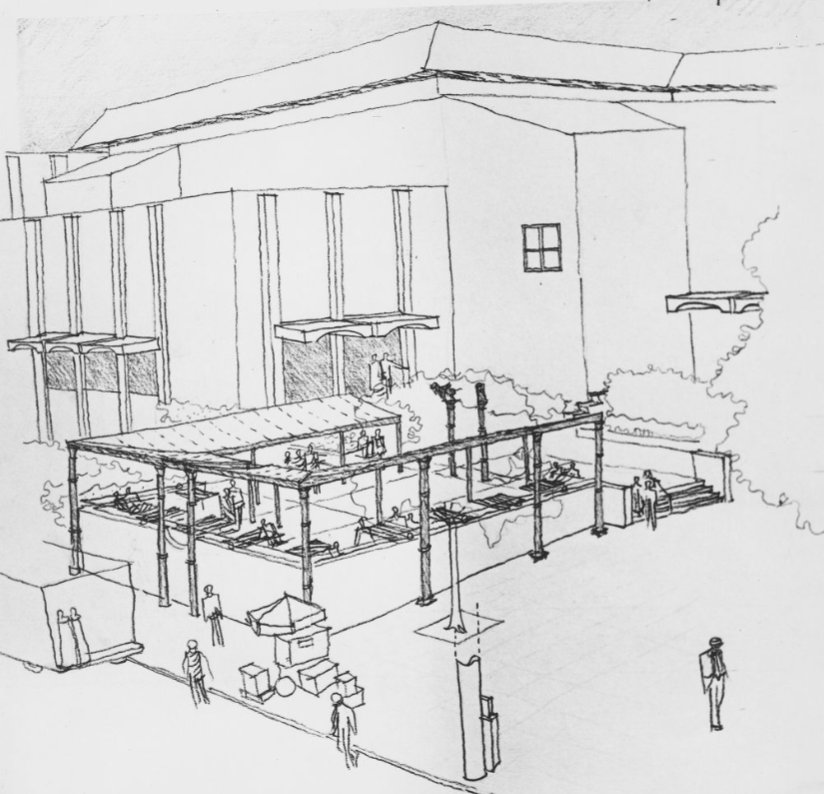

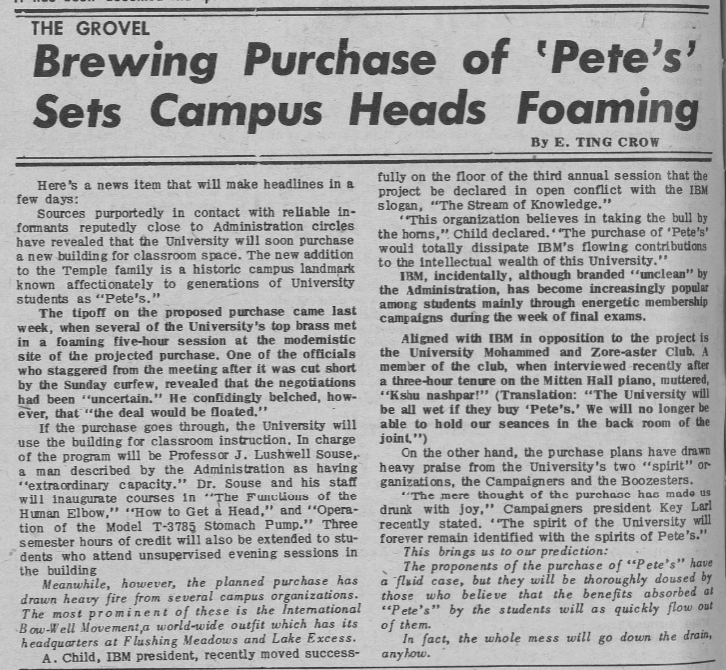

Street took on both Temple and the City Council to protest unlawful tows of vendor vehicles from the street around campus. Street attributed the problems to vendor competition and confusing and discriminatory regulations regarding where and when vendors could set up their trucks. After fighting against the food trucks for decades, in 1982 Temple created a permanent space, the Vendors Mall on 13th Street, for the food trucks. Street drew attention to the ongoing problems, and Temple built a new structure, the 12th Street Food Court, in 1996.

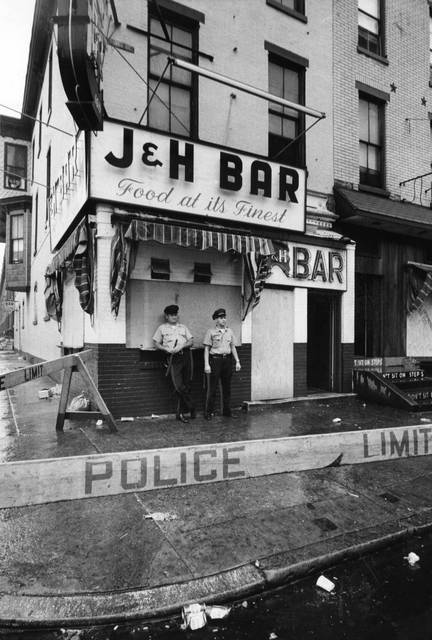

The 12th Street Food Court privileged the few, and the following decades introduced new struggles for food vendors. Parking has always been a concern, and Temple has different options for different kinds of trucks. Some trucks are hardwired into the campus infrastructure, while some are removable carts that can be towed to different locations across the city. In 2015, Temple and the City of Philadelphia created a special Street and Sidewalk Vending District that restricted where food trucks could officially be set up. Trucks were allowed between Diamond, 10th, Oxford, and 16th Street, but not on 13th, the original location of Temple’s Vendors Mall. This ordinance also prohibited the use of generators, enforced minimum open hours for all vendors, and limited the number of total vendors to 50.

In 2019, Temple and the city department of Licenses and Inspection (L&I) once again targeted the operations of the food trucks by announcing they would begin enforcing a particularly difficult rule: vendors would have to remove their trucks overnight, hauling the mobile kitchens in and out everyday. This rule was costly for some food trucks, and impossible for many. Students launched a petition in support of the trucks, and eventually it was ruled that trucks would not have to move each night.

Unfortunately, a new issue was lurking around the corner: COVID-19. The university shut down, and students left campus en masse. Having a semi-outdoor business was actually beneficial during the pandemic given the indoor dining restrictions, but many of Temple’s vendors were unable to move their trucks to find enough customers. Many food trucks went under during the pandemic, and it led to many questioning whether a move to another college campus like Drexel or UPenn would be best.

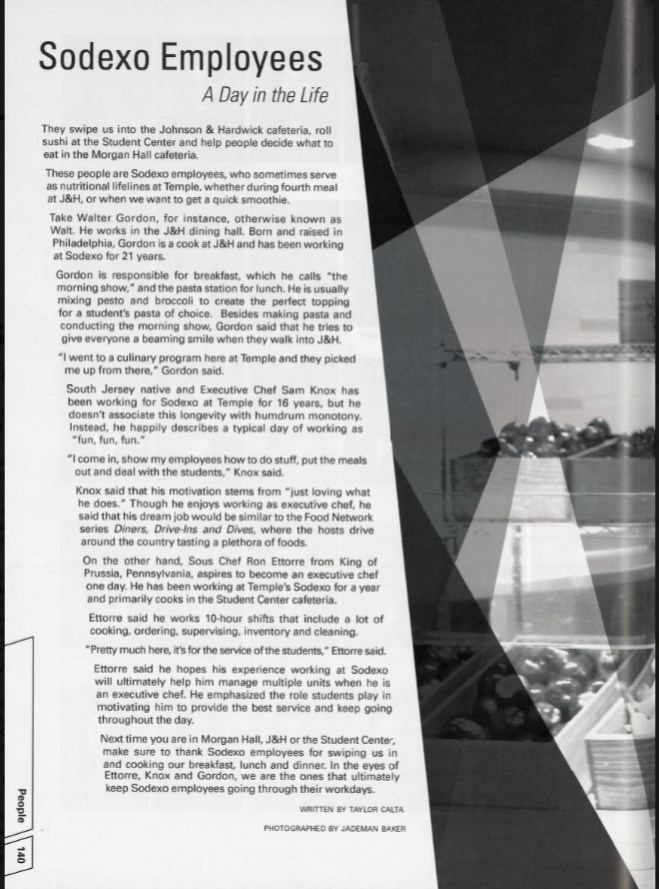

Operating a food truck on Temple’s campus presents many challenges, but students and faculty create affectionate connections with the folks that serve up delicious meals each day. The relationship and support for vendors changes with each university administration, and not all vendors are treated equally. Their presence on campus creates a unique urban environment that has become a talking point of Temple marketing. Students love to debate their favorite spots and dishes, but the truck popularity also draws attention and money away from in-house university food services. Eating at the trucks as a student is making a choice to support local business, but does Temple make the same?

Listen to the stories of Temple’s vendors over at the Oral Histories page.