By Lauren Griffin, Public History MA student at Temple University

Throughout Temple’s history, its students, faculty, and staff have used food to forge community. To raise money for sports teams or other extracurricular activities, students would host bake sales, chicken dinners, or ice cream socials not too different from fundraising practices on campus today. Through food, university students created a network of support not just for their university, but for their peers and the larger Temple community.

One unique food related event was the annual “flour fight” on campus. Sponsored by the Booster Club, 50 sophomore students concealed packets of flour on 20 members of their team. Freshman students were given 10 minutes to search for the packets and dumped them on the poor sophomores when discovered. Less about food and more about the clouds of flour that it stirred up, this was a yearly competitive experience for new students that welcomed them into the Temple community and their traditions.

Temple students bonded together, and the university’s appetite grew, but not for food. This time, they wanted land. In 1955, the Philadelphia City Planning Commission designated the area between 12th, 13th, Norris, and Diamond Street as the Northwest Temple Redevelopment Area, contributing urban renewal grant funds to redevelop the 38-acres under Institutional Development District zoning. The area around Temple was designated as blighted, which misrepresented reality. These were homes, gardens, and life that Temple began razing for their reimagined urban university.

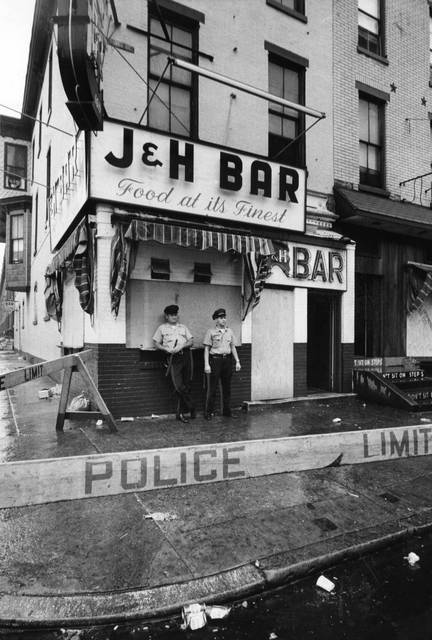

During the 1950s, cities across the United States felt the effects of deindustrialization as factories closed and businesses moved to the suburbs or abroad. Philadelphia’s deindustrialization disproportionately affected its Black residents, and it also heightened the competition within the working-class population as real wages declined and housing costs rose. In the 1960s and 1970s, residents of Yorktown dealt with structural inequality and a predatory housing market that had been preparing for university expansion. The housing crisis, combined with poor economic conditions in the neighborhood, led to the escalation of tensions that resulted in the Columbia Avenue Riots in 1964.

In 1965, Temple became a state-affiliated institution and received an influx of funding to expand their physical footprint. Temple began insulating itself from the rest of the community as they shifted into the next stage of development. Rather than close off Temple from the outside world, certain student groups like the Steering Committee for Black Students fought to integrate with the local community, demanding that residents be granted open access to Temple facilities and fighting for the protection of preexisting houses and community structures from Temple’s rapid expansion. One thing in particular they fought for was public access to the Mitten Hall Cafeteria. Temple dodged these requests, and student activists staged sit-ins to block customers from dining. Temple’s administration finally relented, and public access to Mitten Hall was finally granted. This victory was short-lived, however, as the Mitten Hall cafeteria would soon become obsolete as the new Student Activities Center was built in 1971.

Community access to Temple dining facilities was a nice option for residents, but the situation inside the cafeteria wasn’t exactly stable at the time, either. Students had recently protested the high prices of meals inside Mitten Hall and carried the Brown Bag Boycott. In 1968, a Black waitress at Mitten Hall, Mattie Cross, was fired from her position after a white customer accused her of spilling water on her. The Steering Committee for Black Students protested this and called for Cross to be rehired. They also demanded in addition that all Black employees at Temple be paid the minimum wage and that Temple release an official statement in apology to their Black employees.

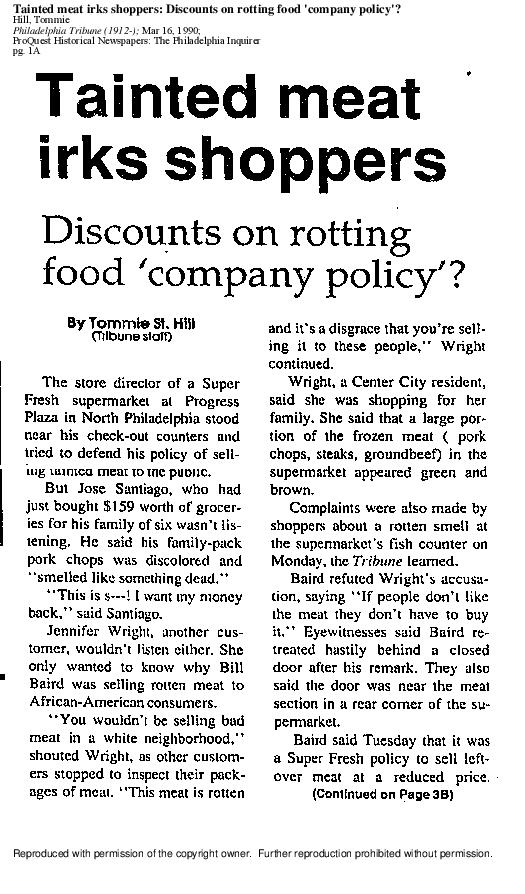

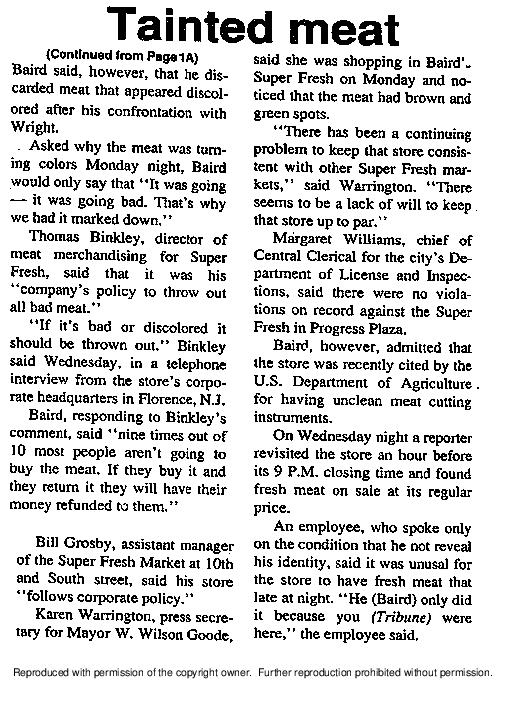

As Temple was in turmoil, the community of North Philadelphia was taking steps to establish their own community spaces. Established in 1968 by Reverend Dr. Leon Sullivan, a prominent civil rights activist, the Progress Plaza at 1501 N Broad Street was the first African American owned shopping center in the United States. The goal of this shopping center was to support Black enterprise and help foster business within the community outside of Temple.

Sullivan made a deal with A&P food store chain for a 20 year contract to have a grocery store in the plaza under Black management. This was a major investment for the neighborhood, but satisfaction with the quality of the grocery store fell over the decades. After the Super Fresh market shut down, the area was left without a local source of affordable groceries, turning it into a food desert.

In 2009, decades after the opening of Sullivan Progress Plaza, the center underwent significant renovations and expansions so that Fresh Grocer, a new grocery store chain, could move into the space. While this was welcome news, the neighborhood still suffers from food insecurity. The area has also been classified as a food swamp, which is an area characterized by mostly low-quality food sources, like fast food chains and convenience stores. Many of those fast food restaurants are there because of Temple University catering to the needs of its students.

When walking around campus, take a look at what food options you see. Are there a lot of big chains or local offerings? What cuisines and ethnicities are represented? Are dietary restrictions and healthy offerings well represented on campus? In looking at the variety of food service in campus, it is also important to recognize who is eating in what spaces, and who is serving.