By Jacob Wolff, PhD student and educator at Temple University

In the final issue of the Diamond Club’s monthly newsletter, Jean Brodey warned that it “may be within weeks of a permanent closing.”

Temple University’s private club featured French wines paired with entrées by an in-house chef. Faculty and administrators were free to saunter about the smoke-filled library, billiards lounge or dining room atop Seltzer Hall while a trio played jazz standards. Occasionally, the president would host a gala.

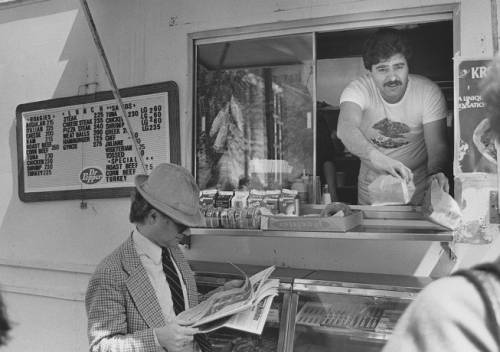

Despite the perks, too few members were taking their meals at the club. Even fewer renewed memberships at all. “Its absence will be felt in many more ways,” Brodey added in the March 1979 newsletter. “Honored guests” would be “entertained at Blimpie’s” or worse, the food trucks.

Administrators intervened shortly thereafter, transferring operations from a nonprofit board to the foodservice vendor under contract with Temple.

Now over forty years later, students and faculty alike line up for a quick lunch from the iconic trucks on campus. Few decried the postpandemic decision to relocate what’s left of the Diamond Club – a lunchtime buffet with a membership option – on the main floor of a dormitory. Why no protest?

For starters, mealtime has never been about the food. It’s about the company you keep.

When members originally chartered the Diamond Club on 9 January 1967 with the Court of Common Pleas, they promised “to maintain an atmosphere conducive to the free and informal exchange of ideas.” Yet, university leaders imagined an exclusive place segregated from the public they were purported to serve. Temple – to its credit and unlike the University of Pittsburgh, New York University, or Boston University – enrolled a remarkably diverse student body in 1967, estimated at 3,100 local students of Color out of the total enrollment of 34,000 students. But, the bylaws were unequivocal: all undergraduates were prohibited from entering the club, barred even as guests of members. Moreover, only staff “earning the equivalent of an instructor’s salary” were entitled to membership, effectively barring working-class employees who were disproportionately Black or Puerto Rican.

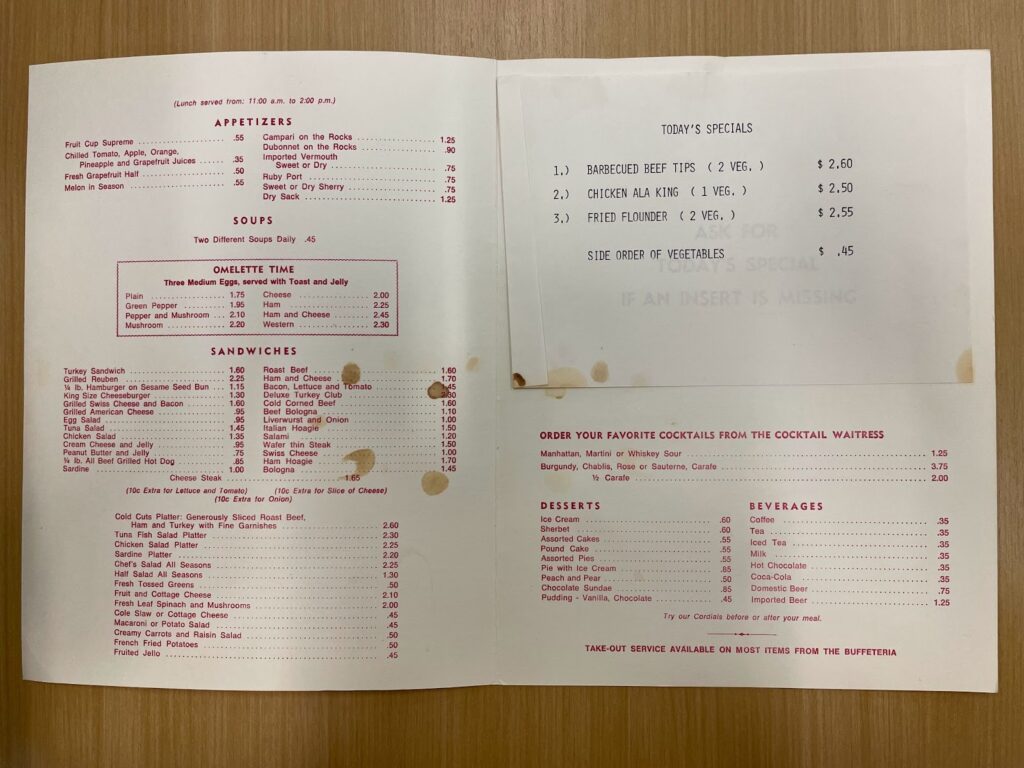

Membership standards, not meal costs, made the difference. For the dwindling Diamond Club patrons, an ambiguous expectation of “cleanliness and neatness” was nonnegotiable with management; whereas, the Club promoted a 50 percent discount on the 50.00 dollar dues in 1978, hoping to win back business. After the university foodservice vendor took over operations in 1979, club dues kept falling (In 2003, dues bottomed out at $5.00 annually!).

No matter the cheapening bill, faculty opted instead to join students over cheesesteak or similar fare at the nearly thirty food trucks that operated on campus by the 1980s. Leo Martella opened the first dedicated food truck on 15 June 1954, selling pizza to Temple students. In 1963, with the federally-backed building boom, more trucks arrived on campus. “You can’t make it with just pizza anymore,” he told a reporter in 1981, “the competition’s too tough.” Wayne’s Deli offered an “Inflation deflator” hamburger special, Maggie’s Oriental Café specialized in MSG-free dishes, and Eddy Eggroll promised “a full line of vegetarian” dishes, including yogurt and fruit juices. Faculty members found more diverse culinary offerings from food trucks than they could on the menu at the Diamond Club.

Some food history scholars believe that middle-class consumers have become more egalitarian in their choices. Others, like Josée Johnston and Shyon Baumann, see “omnivorousness” as “an alternative strategy to snobbery.” In their analysis, diverse rather than exclusive tastes have come to define a cosmopolitan identity. Might the faculty who “slum it” with students and ethnic entrepreneurs reveal a grittier, yet enduring class distinction within our consumer republic?

The answer is probably a bit more complicated.

Dylan Gottlieb, a Temple alumnus (MA ‘13) and historian at Bentley University, reminds us that “we should not mistake [consumer choice] as a substitute for meaningful political struggle.” However, the structural conditions under which university faculty labor have grown more precarious since the original Diamond Club dissolved.

Perhaps faculty consumption mirrors a downwardly mobile status for all university employees. Appropriations from the Pennsylvania legislature have continued to shrink since the “Great Recession” and poorly-compensated adjuncts or graduate students now teach three-quarters of all undergraduate courses in the United States.

Temple employees were on the vanguard of building a collective movement among knowledge workers. Thomas Paine Cronin, president of the Philadelphia AFSCME district, chaired a summit of all campus labor unions in 1983 at the Diamond Club. “As the bread and butter issues get tougher,” he explained, “I think the issue of democracy in the workplace becomes more and more prominent.” By the fall of 1986, faculty went on strike. “Terms of the contract were not made public,” according to the New York Times, “but sources close to the talks said the settlement amounted to almost an 11 percent wage increase in a two-year contract.” In 1990 faculty walked out again – some undergraduates marched in sympathy until a court order forced faculty back to work. Graduate workers were forced to cross picket lines, for fear of losing funding through the duration of their doctoral training. Despite decades of organizing, only in 2001 did the Pennsylvania Labor Relations Board rule that graduate workers at Temple were eligible for union representation. The lead organizer among graduate workers spearheaded a 2019 petition in favor of food truck operator rights.

With annual dues and meal costs averaged $350.00 per person in 1977 (almost $1,800 when adjusted for 2022 inflation rates), and a budding class-consciousness by the 1980s, eligible employees most likely could not afford to join the Diamond Club. Nor did they want to, even after dues dropped. The space, then in the basement of Mitten Hall, was just room available for large gatherings.

No wonder why people hadn’t spilled ink over the 2021 move to Johnson and Hardwick Hall like they did back in 1979. University employees – faculty, staff, adjuncts, and perhaps midlevel managers – no longer want an exclusive space on campus. The food trucks are just fine.

That’s not to suggest private clubs are no longer relevant. Back in the 1960s, the Diamond Club catered to the shared governance of faculty and administrators. Now running a campus is big business. For the select university leaders who can afford it, places like the Union League exist.

To see Jacob's other work, please visit https://www.jacob-wolff.com/