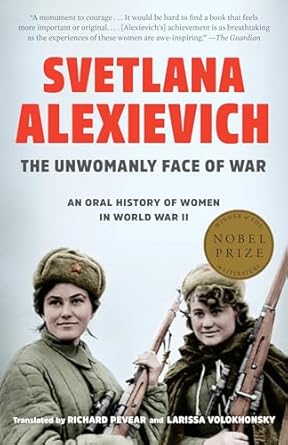

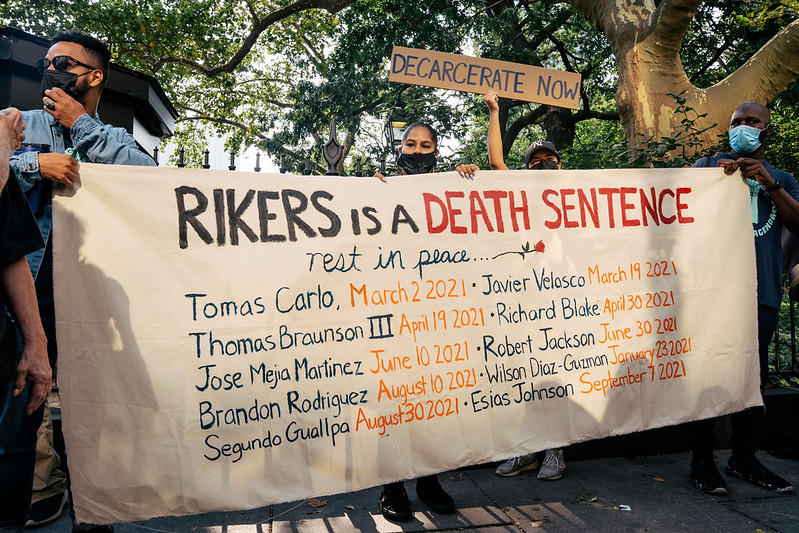

Published in 2023 by the journalists Graham Rayman and Reuven Blau, Rikers: An Oral History tells the history of the prison complex at the Bronx island of Rikers, New York City. This century-old institution, previously the city garbage dump, has been known as a place of violence, abuse and neglect towards the women, men and teenagers incarcerated there, most of them being Black or Hispanic, either convicted or waiting for trial. Relationships amongst the imprisoned and between those and the officers are treacherous and ambiguous, echoing in both of their relatives’ lives, and reflecting the reality of the public power oversight regarding non-white communities to the margins of society.

The book’s goal is to present points of view of the role and effects of Rikers within the city that surrounds it. Therefore, not only former and current incarcerated people were listened to, but also their families, officers and high staff, lawyers and activists of public policies. From the 130 interviews made, the authors selected common themes and transformed those in chapters: starting from day one in the prison, they address racial, gender and sexuality experiences and the quotidian dealing with constant and multiple forms of violence, perpetuated both from the state, the prison administration and the imprisoned.

Overall, it is a great book, especially if you are into criminal studies, and an easy read if you take in account the structure and organization (the toughness of the subject can make it hard to digest, though). Each chapter starts with a brief introduction from the authors, followed by excerpts of the interviews – always with a prior indication of the narrator, but rarely with the question made. I struggled with some of our readings through our class because, in my point of view, there is little justice being done when authors use chopped fragments of OH in their writings. After reading Rikers, I understood my preference for longer statements, since they provide more a line of reasoning from the interviewee’s speech; and personally, the absence of the authors’ mediation between different stories is not a problem. Actually, Rayman and Blau did an ingenious work on showing content patterns and chronological perceptions by combining narratives from varied people in a logical order with a beginning and an end at each chapter.

A lot of the choices made by the authors lack explanations, like the reason why only Linus Coraggio (artist, detained for one night, not in Rikers), Amin “Minister” King (today personal trainer and body guard, imprisoned at Rikers in the 80s), and Michael Jacobson (correction commissioner) have their own exclusive chapters, the latter two with other appearances too. Also, and the profile of Corragio illustrates it, it is not clear why people incarcerated in other institutions figure in the book and how they were chosen amongst others (as another example, Sandi Sutton was detained in Greenwich Village at Women’s House of Detention). To be fair, I appreciate their inclusion, because it provides a statement of how there was and is little difference between carceral institutions across the country. The authors never said they were going after this, though; from the preface and additional contents (such as the book flap), the idea for the book is to be about the effects of Rikers on people’s lives. At last, there are a few interlocutions between two narrators that are unclear if they are artificially juxtaposed together or if they were actually together at the time of the interview.In the end, as it happened with a lot of other readings we did this semester, it may be difficult to encounter projects that fulfill all the paradigms and rules posed in the OH manuals or by the OH Association. It has to be valued, for example, the authors’ concern with the material availability for the general public; after all, the Rikers Public Memory Project is collected at The New York Public Library, and anyone can require an in-person research appointment through their website. At the same time, interviews were sometimes made in cafes or cars or even inside the prison, where a few interviewees were still serving time – this adds a safety layer that I see as a limit being challenged, with possible negative outcomes. In my personal view, the book should be considered as part of a broad tradition of Oral History works, but it should also have its methods and choices questioned in the light of a system that is still overlooked by historians.

Bibliography

Rayman, Graham; Blau, Reuven. Rikers: an oral history. New York: Random House, 2023.