Since our first conversations in class, it has become clear that Oral History (OH) has had both a huge appeal and concerns regarding its reception by historians. This week’s authors lead ourselves through this path, helping us to identify tendencies and contextualize the intrinsic nuances that come within.

Once we begin with Nevins (1966) and Starr (1977), the idea of Oral History as a potential revolution in historiographical work seems to have prevailed in the face of the supposed obstacles overseen. Besides the issue of financial aid, which should not be ignored or minimized, Nevins points out a growth of new OH products – exponential volumes of interviews and transcripts – and works beyond the United States borders. These statements are corroborated with the quantitative work presented later by Starr, with a first peek of American programs and articles on OH in 1970, a few years after the establishment of the Oral History Association. In order to be institutionalized as a valid product within the pairs, practice guides and manuals were written, serving as promotional material but mostly as a way of creating basic standards.But there was an issue back then, which we should be familiar with: whenever something new comes up, people tend to either discredit all of the efforts or romanticize it as the solution for all of their problems. This may be the case of OH as its own method was still being developed during the 70s and the 80s; what seems to have happened is that people were so amused by the idea of being closer to the truth that they understate the difficulties of implementing the use of oral sources in a human science so attached to the writing. Although someone could argue that the next were only ways of saying, or attempts to make oral histories appealing to funding institutions, statements about how OH “saved from death’s dateless night”¹, how a good interviewer may help someone to “stuck closer to the path of truth”² or how oral histories allows someone “to bring to light a genuinely subterranean history”³ probably influenced the avant-garde in taking a step back. This is not saying that our authors believed that there is a truth, even because all of them emphasize the need of crossing-evidence and bibliography, as well as the importance of pair review to enhance the practice of OH. On the other hand, this certainly helps to crystallize the idea that the past can be discovered by an objective and neutral historian. Well, this is the key question I would like we could discuss: does it make sense to worry about those statements or is it merely a linguistic problem or a figurative type of language? Did you feel the same once reading it or it comes in a natural way? Are there any implications to our work by addressing those or not?

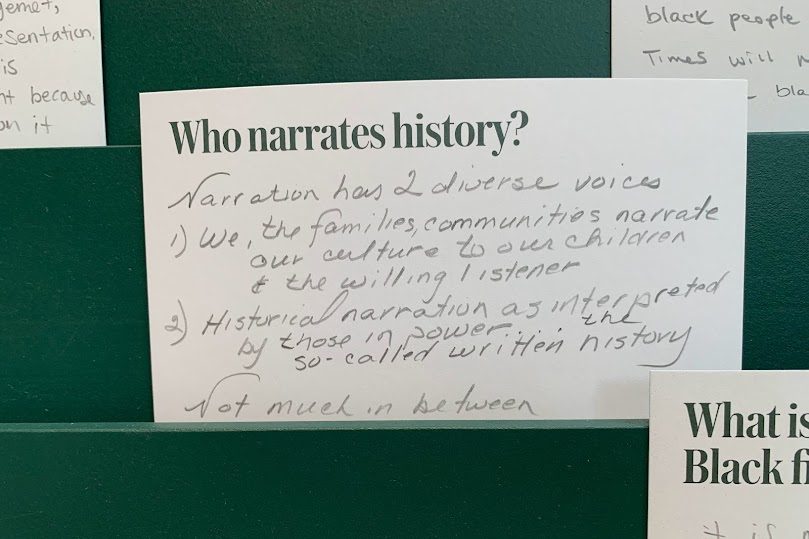

Portelli’s work made me feel welcomed in these matters. If OH is capable (and I believe we all agree with it) of filling lacunae left by a historiographical tradition based primarily on writing, understanding its limitations is equally important for our work. After all, our professional education does not train us to reveal the past as it really happened, but to give it meaning in a cohesive narrative through a critical analysis of the inherently subjective sources that we have at our disposal. Not only are our sources produced and preserved by human action, but our interpretations of what they say and mean are also shaped by our individual and collective experiences in the time and space we occupy today. Rather than being a bad thing, acknowledging this emphasizes our capacity to be responsible for our historical production.

Footnotes:

¹ NEVINS, p. 30.

² NEVINS, p. 37

³ HALPERN, p. 606.

Bibliography:

Nevins, Allan. Oral History: How and Why it was Born. In: Dunaway; Baum. Oral History. An Interdisciplinary Anthology. 2nd edition. AltaMira Press: 1996.

Starr, Louis. Oral History. In: Dunaway; Baum. Oral History. An Interdisciplinary Anthology. 2nd edition. AltaMira Press: 1996.

Halpern, Rick. Oral History and Labor History: A Historiographic Assessment after Twenty- Five Years. The Journal of American History, vol. 85, no. 2, Sep. 1998, pp. 596-610.

Portelli, Alessandro. What Makes Oral History Different. In: ___. The Death of Luigi Trustulli and Other Stories. State University of New York Press: 1991.