Dana Dawson, Caitlin Shanley and Stephanie Fiore

The most common forms of information literacy education in recent decades have focused on developing our students’ ability to find sources and use them effectively and ethically in support of a thesis. The development of skills related to source identification and evaluation for scholarly purposes is undoubtedly an important outcome for college-level studies. However, the revised Framework for Information Literacy in Higher Education, developed by the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL), Trudi Jacobson and Thomas Mackey’s work on metaliteracy and numerous studies conducted by Project Information Literacy have shown the need for a revised approach and provided new tools for addressing information literacy. Given the volume of information our students are exposed to on a daily basis, it is critical that they graduate with an enhanced awareness of how the information ecosystem works, how emotion influences the information we believe and act upon, and how investigative skills used for scholarly study can and should be applied in our everyday lives. Here are some approaches to consider for your own classroom.

Metacognition

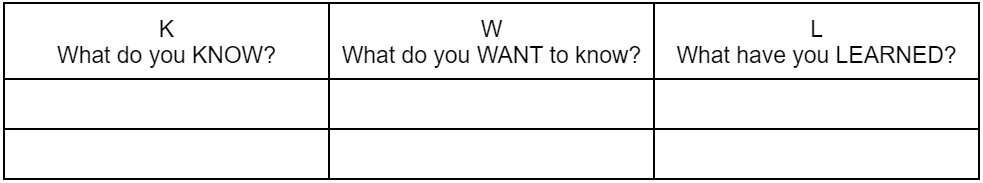

Metacognition involves reflecting on our cognitive processes and developing an awareness of how we think and learn so that we can adjust our behaviors on the basis of what was effective. Applying metacognitive strategies allows our students to take control of their educational process and make connections between prior knowledge and course content. The metacognitive process for learning involves an iterative cycle of planning, monitoring and evaluating one’s learning with focused self–questioning at each stage.

This same metacognitive process can be used to develop a reflective stance on the information we’re exposed to in our studies and everyday lives. To help our students become more critical and reflective consumers of information, encourage them to apply the tools of the metacognitive process to their information consumption. In order to improve information literacy, students can ask themselves questions such as::

- Planning – What sources have I selected to read/watch/listen to and why? Will I look at multiple sources on an event or topic? Why am I reading about/watching/listening to this?

- Monitoring – What kinds of information are more likely to appear at the top of my feed? How am I feeling as I read/watch/listen to this? Do I agree with the information being presented because it has been verified or because it aligns with what I already believe? Am I investigating claims before forwarding them to others?

- Evaluating – Did I spend more time on certain types of sources than others? Whose information was I more likely to believe and share with others? Were my efforts to investigate sources and claims using other sources successful?

Ask good questions

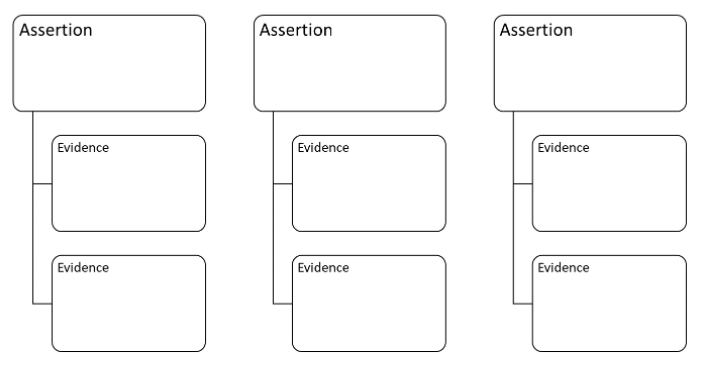

Generalized skepticism is among the challenges instructors face in relation to information literacy and “I’m just asking” is one of the most potent tools for spreading distrust of substantiated information. However, learning to ask good questions for the purposes of investigation and verification is a foundational skill for scholarly study and conscientious consumption of information. Dan Rothstein and Luz Santana’s Question Formulation Technique is a strategy instructors can use to prompt students to not only generate questions but reflect on and prioritize the questions that will generate the most productive investigation.

Lateral reading

In a small but provocative study comparing the website evaluation strategies of Stanford students and history professors with those of professional fact checkers, Wineburg and McGrew found that fact checkers applied two strategies neither students nor faculty immediately went to – “taking bearings” and lateral reading. Rather than evaluate a source by digging deep into the source itself (for example, applying the CRAAP test), fact checkers started by learning more about the website or source and then opened new tabs and found additional sources to investigate claims and sources on the website as they read content on the initial site.

SIFT method

The SIFT method combines elements of metacognition and lateral reading into a simple mnemonic for evaluating claims.

- Stop

- Investigate the source

- Find better coverage

- Trace claims to their source

Connect classroom activities with everyday life

Our students come to our classrooms with some awareness of how information is manipulated and with strategies for finding and evaluating sources. However, the very human tendency to compartmentalize information means that we need to be proactive in connecting what happens in the classroom with the strategies applied outside the classroom. If you assign a research paper or project, start with a reflection on how students find information in their everyday life. Use analogies such as crime scene investigations or learning more about a possible romantic partner to encourage deeper thinking about how we ask questions and seek additional information. LaGarde and Hudgins encourage instructors to have students use personal devices such as cell phones to do some searching to help make the connection between search strategies learned in the classroom and those employed in everyday life.

Inoculate against mis/disinformation

Finally, recent research on protecting against mis- and disinformation has suggested the efficacy of “inoculating” students against future exposures. Strategies such as explaining misleading argumentation techniques, demonstrating how content is designed to manipulate emotion and showing how certain types of content are more likely to be prioritized on platforms students access can reduce the influence of misleading information going forward. Sites such as Bad News Game can be used to help students understand how platforms and content creators play on our emotions and pre-existing beliefs to increase viewership and readership. Lorenz-Spreen et.al. have also shown that such interventions in combination with self-reflection on aspects of our personality or behavior that might be targeted is particularly effective in boosting one’s ability to detect manipulative strategies.

Additional Resources

- Algorithmic Justice League www.ajl.org

- Digital Citizenship Resource Platform https://dcrp.berkman.harvard.edu/

- News Literacy Project https://newslit.org/

- Project Information Literacy: https://projectinfolit.org/

Sources

- Downey, A. (2016). Critical Information Literacy : Foundations, Inspiration, and Ideas. Library Juice Press.

Dana Dawson is Associate Director of Teaching and Learning at Temple’s Center for the Advancement of Teaching.

Caitlin Shanley is the Coordinator of Learning & Student Success at Temple University Libraries.

Stephanie Fiore is Assistant Vice Provost at Temple’s Center for the Advancement of Teaching.