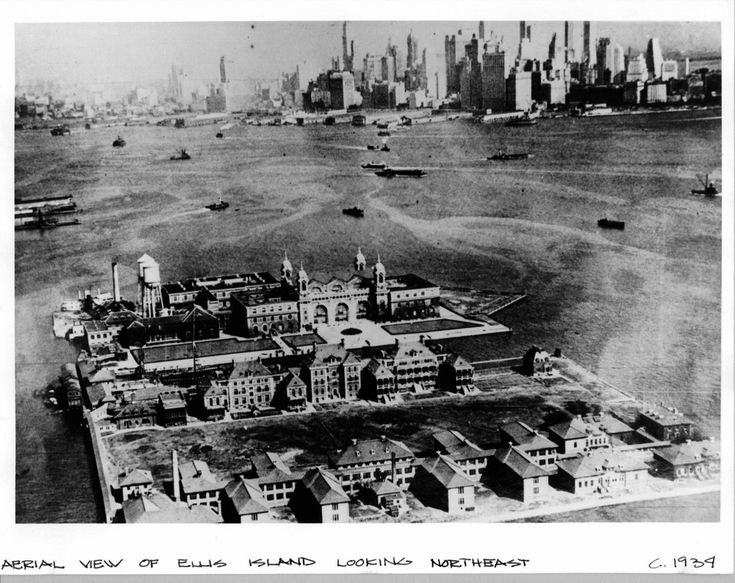

On Saturday, February 7, 2009, Australian officials recorded more than 400 individual bushfires burning in the countryside of the state of Victoria. Although the countryside would continue to burn for weeks afterwards, February 7, 2009 became known as “Black Saturday” because 173 people lost their lives to the fires on that day. For this reason, the Black Saturday bushfires are among the most vigorously documented wildfires in history.

Dr. Peg Fraser earned her Master’s Degree in Public History and Heritage at the University of Melbourne in 2008. By 2010, she had joined Museum Victoria as a curator. She started the process of earning her PhD (also in History) at Monash University in 2011. While working on her PhD, Fraser, in her capacity as a museum curator, began collecting oral history interviews for the Victoria Bushfires Collection. Later, after graduating with her PhD in 2015, Dr. Fraser used more than twenty-seven of her interviews from the Victoria Bushfires Collection as the basis for her book.

Published in 2018, Black Saturday: Not The End of the Story is primarily a cultural history of the town of Strathewen, one of the many small settlements outside Melbourne unlucky enough to exist in the bushfire’s path. Limiting her oral testimony to those from one town sacrifices breadth for depth, allowing Fraser to explore the greater context of Strathewen’s existence prior to the fires in a level of detail which would prove challenging to fit in a documentary. Although Fraser’s approach bears fruit, this reviewer can only wonder how similarly or differently the other towns experienced the fires and aftermath. Perhaps future scholars will take up those explorations.

Fraser mixes Black Saturday’s oral and editorial primary sources with papers from local historians and settler families, along with an intriguing analysis of material culture. For secondary sources, she draws from scholarly literature on Australian environmental history (bushfires), memory studies (memorials), feminist literature (gender and disaster), and trauma studies. Rejecting the idea that she needed to find a master narrative of the bushfire, Fraser chose to focus more on analyzing how the survivors told their stories and what that means for both the storytellers and their listeners. Dr. Fraser’s background as a public historian and museum curator, and especially her interest in material culture, is easy to spot within Black Saturday. Featured in the book’s eight main chapters are eight photographed objects, artifacts touched by or directly related to the bushfires, that provide readers with entry points into the broader themes of Fraser’s narrative.

A broken Trewhella jack, for example, which is an obsolete tool previously used in the sawmills established in the bush outside Melbourne in the early days of Strathewen’s history, allows Fraser to dive into the history of Strathewen’s settler origins, the rise and fall of the apple orchard industry, and the gradual encroachment of urban culture from Melbourne.

A map showing the fire line (how far fire reached before changing directions and dying out), hand-drawn by a Strathewen survivor shortly after the blaze, prompts Fraser to analyze how survivors dealt with the aftermath of the fire. Survivors’ experiences of the aftermath were varied. Some lost more than others, leading to complicated emotions existing between survivors, but as Dr. Fraser aptly argues, “Everyone in the bushfire zone, to one degree or another, is burnt” (226).

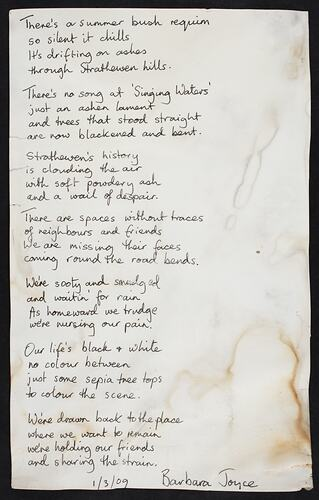

– A poem originally posted on Strathewen’s Poetry Tree

Fraser uses a burned tree, covered with poems written and posted by Strathewen’s survivors in the immediate aftermath of the fire, to explore how the memorialization process produced flattened narratives of an idyllic, harmonious Strathewen that never actually existed. This tree, referred to as the Poetry Tree, was eventually ‘replaced’ with a permanent memorial conveying the same sort of message. Fraser argues that memorials like the Poetry Tree are not meant to express an accurate snapshot of history; they are instead designed to put forward a story that helps grieving people find the strength and inspiration to continue with their lives. “We just have to remember,” writes Fraser, “especially when reminded by those whose experiences contradict the harmonizing narrative, that it is not the whole story” (226).

A poster declaring “THERE IS NO HEIRARCHY WITH GRIEF AND LOSS”, which was displayed after the fire at a nearby relief center for Strathewen’s survivors, ushers readers into the tangled social hierarchies by which survivors measured both their losses and their willingness to accept help from official and unofficial channels. Survivors dealt not only with callous attitudes and comments from outsiders, but also with judgment and gossip from their own fellow survivors. Strathewen’s survivors collected many of the callous comments they received from outsiders and wrote them down on posters like the one featured in this chapter, which ultimately transformed the hurtful sentiments into something survivors could bond over and laugh about. By “repudiating a hierarchy of grief and loss,” according to Fraser, the posters “were acknowledging its existence” (97).

One Strathewen survivor’s old cellphone, blackened and partially melted from the heat of the fire, provides Fraser with a doorway into how the survivors made sense of and told their stories. People processed the trauma and interpreted it differently. Longtime residents of Strathewen, particularly the descendants of the original settler families, had experienced major bushfires before and tended to view their experience through narratives of loss, endurance, and renewal. People who had only recently moved to Strathewen, who did not have a deep familial connection to the bush or experience with wildfires, tended to view Black Saturday as a catastrophic end-of-the-world event that rendered the past unrecoverable, similar to being cast out of Eden. Some survivors told stories about how Strathewen came together as a community; others, who did not enjoy good standing in the community, instead invoked national narratives, such as that of Australian resilience (a narrative Fraser links to Australia’s dismal failures in the Gallipoli Campaign of World War One).

A child’s drawing of a chook (a chicken or fowl) introduces the Chook Project; a local initiative in which some of the women of Strathewen sewed chook cushions to distribute to any fellow survivors who wanted them. The fact that only women worked on this project launches Fraser’s analysis of the role played by gender in the survivors’ experience of the disaster. “On Black Saturday,” Fraser concludes, “some decisions to stay and defend (or to stay and be defended) were made not according to an assessment of risk and preparedness but according to gendered emotional concerns and relationship dynamics” (228). Binary gender roles among white settlers in the Australian bush usually show up as men working the land while women work the home. Because men are the ones traditionally expected to defend their homes from bushfire, staying to protect one’s home became entangled with notions of masculinity, making it more challenging for women to assert themselves during Black Saturday.

Black Saturday does not follow Frisch’s model of shared authority. Despite feeling guilty for not doing so, Fraser defends her choice by asserting that if she had followed the shared authority model, Black Saturday “would have resulted in a very different book” (260). She does not elaborate upon how her methods diverged from those espoused by Frisch, but I assume it means her narrators did not have input into the form Fraser’s book took or into the narrative Fraser adopted. I can understand her reluctance. Shared Authority is difficult to implement. A person’s relationship to and understanding of any event morphs greatly over time, and this is amplified when dealing with traumatic memories. Some of Fraser’s narrators tended to embellish or distort the facts because, to them, crafting narratives that provide meaning for why their friends and family members died took greater precedence over telling the story as it actually happened. Attempting to co-create a book so soon after the fires with a grieving, overwhelmed community might have ended disastrously. Still, I can only wonder what form Black Saturday might have taken had Frisch’s model been implemented.