Donald J. Raleigh’s book Soviet Baby Boomers provides a fascinating social and cultural oral history of America’s generation equivalent. The book, through conducting over 60 interviews with graduating classes from school No. 42 in Saratov and from No. 20 in Moscow, outlines and describes how they lived “Soviet” and what that meant to them personally. The interviewees themselves are fascinating, but Raleigh provides than just their testimony. Raleigh takes a global historical perspective, situating his interviewees’ domestic social and cultural histories, responses, and articulations into the wider context of global, Soviet, and Russian dynamics. The book is likewise astoundingly well-researched into each interviewee’s own personal history, their parents, and their grandparents. As a result, Soviet Baby Boomers covers the entire history of the Soviet Union from 1950 and into Russia until 2004.

A particular strength of this book is how Raleigh uncovers attitudes and perceptions of the state during the Cold War, the threat of nuclear war, academic competition with the United States, their slow disillusionment with the Soviet “dream” after Khrushchev’s speech, introduction into the workforce, and economic troubles with the eventual disintegration of the Soviet Union. The sections on Soviet consumerism are particularly relevant in the current Soviet cultural and social historiography. Raleigh even dedicates a behemoth of a chapter, in quality rather than quantity, to the unfortunately under-researched 1991-2001 Russian “Troubles” epoch.

Structure and Method

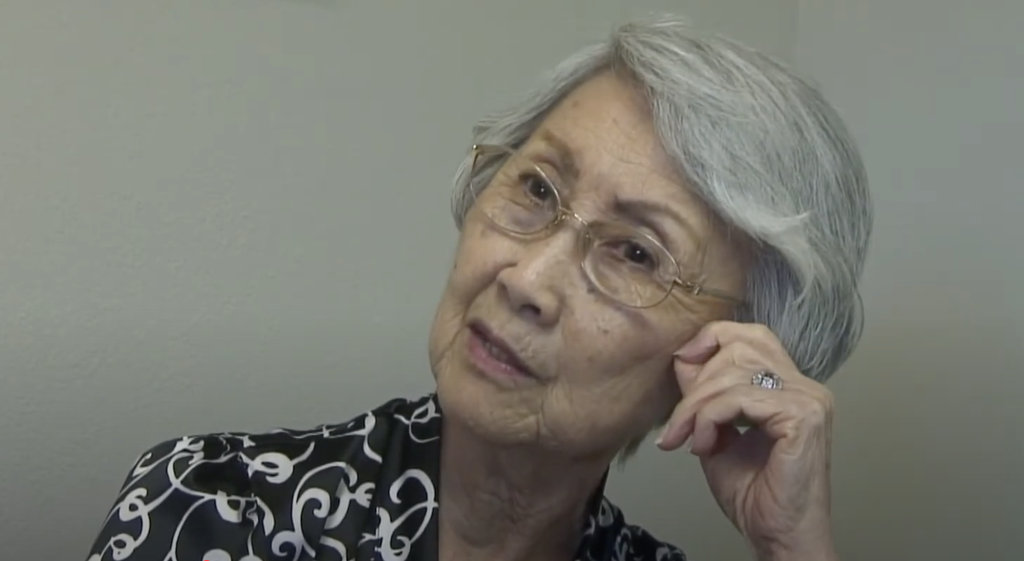

Raleigh interweaves every interview beautifully into the book so that it never breaks the book’s flow, narration, or writing style. Raleigh’s inclusion of when interviewees decline to comment, seemingly omit, or ignore certain periods of time or events, is handled with tact and respect. Raleigh nonetheless comments on these omissions or lapses, provides an analysis, and incorporates them into a wider historical context. Equally commendable is Raleigh’s explicit clarification, in the introduction and conclusion, about the issues of memory and narrativization when conducting Oral History, and elaborates that these interviews illustrate how these Russians viewed and interpreted their own history rather than treating them as absolute fact.

Despite these accomplishments, there are various structural and methodological inconsistencies within the book that clash with contemporary Oral Historian practices. Most notable is the lack of information on when these interviews were conducted, where, or how. Equally unfortunate is any information on where, or if, these interviews were archived or are currently available. In lieu of this fact, a rather discomforting silence persists throughout the book. As Irina Vizgalova’s father told her and Raleigh laments: “ ‘Don’t poke your nose in politics, because they’re good at rewriting our history.’ But so are we.” Perhaps a more transparent and accessible Oral History could have changed my perception of this end-of-the-book quote.

Raleigh, Donald J. Soviet Baby Boomers. Oxford University Press, 2012.