Hurricane Sandy on New Jersey’s Forgotten Shore is a fascinating and impressive Oral History project. However depressing and sobering its effect, it nonetheless testifies to the power that Oral history can provide in historical research. There is more color, depth, emotion, and commentary on the human condition and spirit within Perkiss’ book than in a number of histories I’ve read previously. This book places New Jerseyans front and center in their own history, in their own lives, vividly illustrating the tragic nature of those who never expected to be center stage.

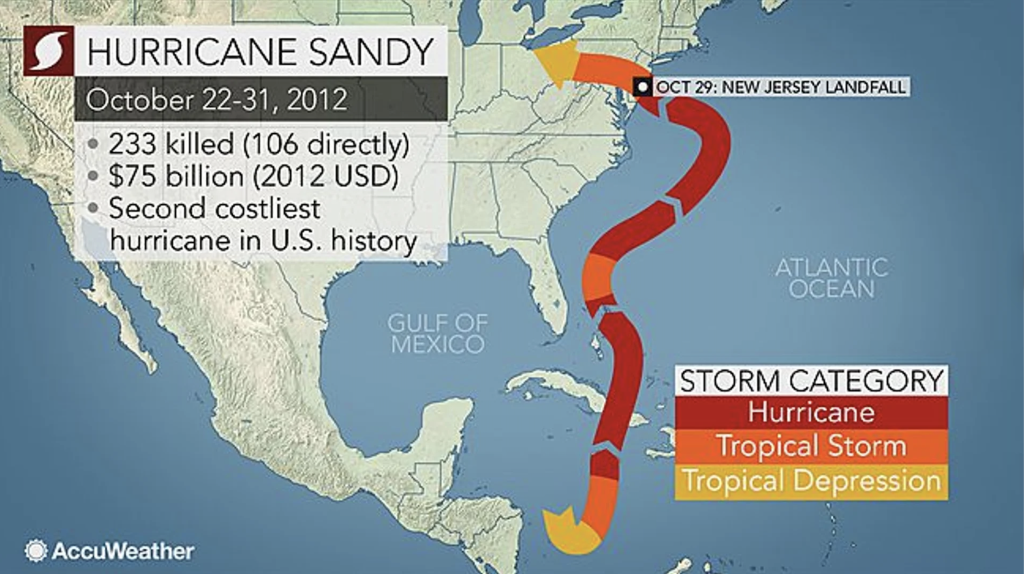

Perkiss’ and her students, who interviewed an impressive number of New Jerseyans, completed most of the interviews within ten to fourteen months, and the remaining just shy of two years, of when Sandy made its initial landfall on October 29th, 2012. The research, planning, outreach, and processing of such information would have been an immense task to complete within those two years. Perkiss’ research, planning, and organizational process to complete the majority of her interviews within the ten-month time frame raises several questions, however. Not simply that this would require an intense workload, but rather for the rigorous research process that is supposed to accompany an Oral History. For many of those featured prominently within the book, the time it would take to research them, their own history, their town’s history, and Sandy’s impact upon their future, would be hard to complete within two years, let alone ten months. This raised a myriad of questions while reading the book, that I would have liked to have seen included within the text, but ones that I do not, in any way, think detract from the effectiveness, nor the importance, of the history provided. The first set of questions therefore comes from the quality of research that can and could be conducted within such a short period of time. But this is not to say that the research within the book itself is rushed or misleading.

The second set of questions comes from considering Oral History’s often close relationship in dealing with trauma. The author’s voice and narration cover all the aspects and conditions of trauma throughout the book, in the hurricane’s physical destruction, financial destruction, emotional and physical fatigue, but it is never the center of the dialogue. It is inferred and depicted throughout, in the many forms listed above, but is never in active voice or directly engaged in dialogue.

The third set of questions centers around its approach to the interviewee. The book’s focus, interestingly, is focused more on the individual, personal, human history of these individuals. The main character, Sandy herself, is treated as a secondary character. New Jerseyans’ lives and histories are affected by Sandy rather than vice versa. The central focus of the book is on these New Jerseyans, whose lives are uprooted and disrupted by the storm, rather than treating Sandy as the principal agent. This flips the narrative in quite an effective way and makes the book a history of the Human condition, and in many cases, spirit, rather than on the hurricane. While reading, I thought of Swing Shift and how the books differ in their focus and approach. Swing Shift’s approaches to the interviewees as both main characters and supplements to the history of all women’s jazz bands in the 1940s. Yet, in many chapters, though certainly not all, the lack of quotes and direct narration from the interviewees themselves transforms them into footnotes, research to supplement the history. Perkiss flips this and puts the interviewees themselves front and center and relegates Sandy to the footnotes. Research on the storm is merely secondary to the research on the personal, very alive, colorful history of New Jerseyans living through this tragic period.

Comments