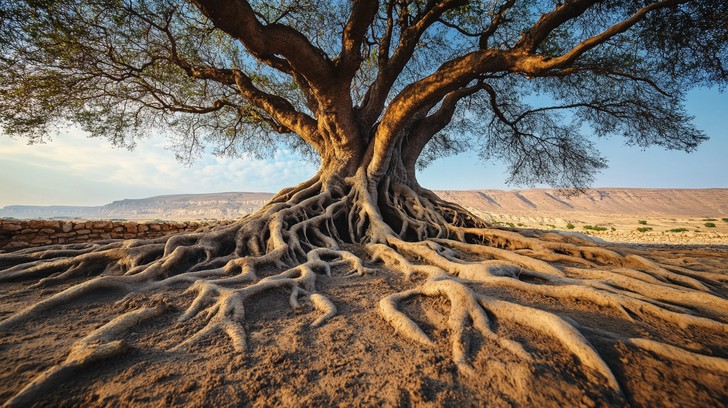

Oral history is an extremely dynamic process. In its dynamism, beyond its many layers of subjectivity, there is a fundamental issue of structure. Specifically, a solid, stable, continuous structure of memory. To substitute an analogy of the brain for a tree, we can see that an interview comprises the structure that is above ground, but also a vast and complex subterranean structure. Its structure is dependent on its type, family grouping, environment, collective organism, and/or whether it responds adeptly to external stimuli. Below the obvious above-ground structure of the tree, we encounter the roots and their intricate layers of memory, meaning, and purpose. Each cannot live without the other, and an analysis of each is likewise incomplete. In this daft analogy, I seek the source that sustains and nurtures these roots, the deep subterranean groundwater, steeped in dirt, memories, and minerals, meaning and purpose. This groundwater, through an arbitrary and seemingly random process, irrespective of consciousness, decides which roots to nourish and which to let die away. These roots, which grow stronger by the season, combine both the narrative and the performative nature of Oral History. Its above-ground structure is only visible.

It is therefore important to understand that Oral Historians are not aware of the roots, which ones are stronger than the others, nor which ones lead to the underground reservoir. The Oral Historian must excavate as tactfully, morally, and ethically as possible to observe the root’s structure. Our job is neither to de-root nor de-forest.

As all people do, the interviewee has an irresistible inclination to narrate and perform. They have an interested and invested audience to explain such a narration: an understandable, chronological, delineated account of all major areas of their life. They have created, or perhaps manufactured, their own history. They have collected a multitude of sources, battled dissent, found like-minded individuals, reinforced their idea of self through trials and tribulations, and have constantly annotated and revised their story throughout their entire lives. The history they were witness to, or directly involved in, is directly transfused to their sense of self.

The introduction of the interview is akin to an examination. They have to perform. For the deepest, often traumatic, most integral memories and moments in their life, sexual assault survivors, war veterans, and survivors of genocide, the interview can inadvertently become a larger examination of their lives. Whether that is an examination with or without apparent judgment depends on the skill, tact, and ethical construction of the Historian.

But what if we conduct oral history on a seemingly mundane point in an interviewee’s life? On a time period that is neither particularly relevant in their life-story, ethos of self, or performative narrative? Does the sudden interest of two researchers co-opt an individual to perform, to narrate, to construct their interview in the context of their life? Can their roots even be observed in a seemingly less important part of their life? Is an interviewee not interested in the history we seek to research, a more reliable source? Do we seek out a senior employee or a relatively new one? Can interns provide more reliable information about the interworkings of a company, as opposed to their boss, or even their CEO? They will have less to lose, fewer inhibitions even. Surely, the issue of guarded language and the performance is the fulcrum on which the truth teeters for the Oral historian. What does are tree look like really?

Comments