Gladys Okada was born in Eleele on the island of Kauai, Hawaii. Both of her parents emigrated from the Japanese mainland not long before her birth. She graciously took part in the Oral History Center’s project “Rosie the Riveter WWII American Home Front Oral History Project” in 2014 and recounted her life in Hawaii during WWII and the post-war era. Most prominent throughout the interview were her memories of working at the McBryde sugar plantation and how her life progressed after Pearl Harbor. Gladys goes into great detail about her parents’ Japanese history and culture, as well as her neighbors throughout the village. It is surprising then that the American government interned neither her family nor her neighbors, especially since her parents still had relatives in Japan. Gladys does mention that some relatives of hers on the mainland were interned, but neither she nor her interviewers go into further detail about this. Despite this unfortunate departure from one of the more interesting accounts of Gladys’ unique experience, the interview is quite fascinating. Her story is so rich, and one that helps to voice the usually softened or silenced history of Japanese Americans during WWII.

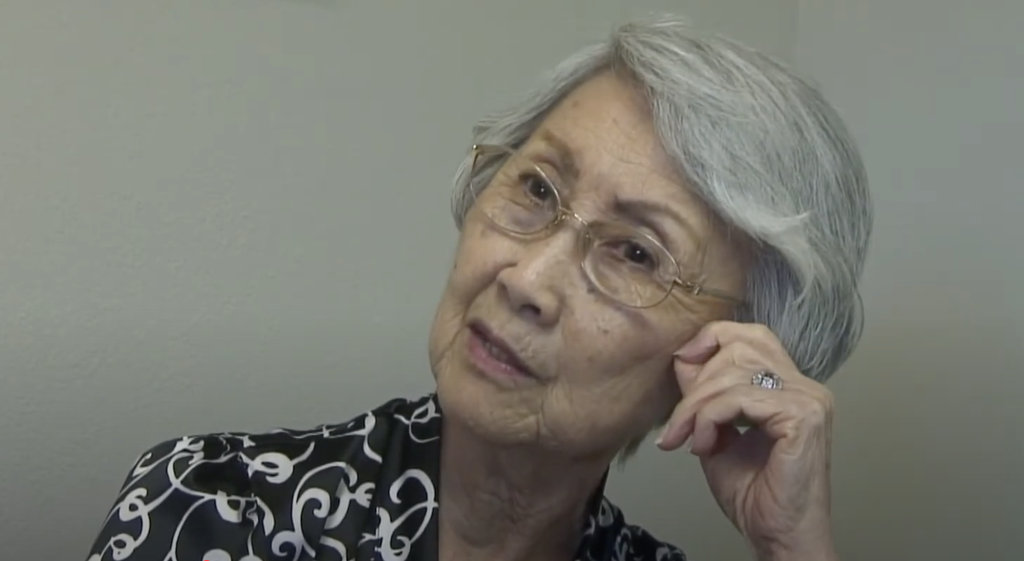

Yet, there are a couple of aspects of the interview procedure that hampered the otherwise fascinating history that Gladys recounts. Although not immediately obvious if just listening to the interview, the video accompaniment illustrates friction between Gladys and one of the interviewers, David Dunham. Contrasting this, Candice Fukumoto, the other interviewer, demonstrates an obviously good rapport with Gladys as she laughs with Gladys’s smiles and small instances of humor. Dunham is often silent during these more casual, conversational-like aspects of the interview, which is a shame because this is when Gladys shows her personality and opens up the most. Dunham was also prone to interject during the latter half of the interview, presumably to direct Gladys or divert her to a specific topic he is most interested in capturing. From my perception, these do a disservice to the entire interview and to Gladys. In these cases, Gladys’ train of thought falters; she has to lean in to hear Dunham, who often has to repeat his question, and then has to reorient her memory to answer Dunham’s question. There are trace amounts of frustration in both Dunham’s and Gladys’ voices throughout these interactions. Gladys is usually re-telling an important, humorous, or fond memory when she has to re-orient herself to these interrupting questions, resulting in her welcoming smile dropping, brows furrowing, and short one or two-word replies. She then has to pivot to a topic she is less interested in talking about.

I think some of these, quite surface-level issues, could have been alleviated by improving the interviewing process. Firstly, and perhaps most importantly, would be to diminish the distance between Gladys and Dunham. Dunham appears to be a good distance from Gladys, and certainly much further away than his colleague Fukumoto who is only a foot or so away from Gladys. This also causes Dunham’s voice to be barely picked up by the microphone attached to Gladys’ shirt, which causes Gladys to have to lean in to hear Dunham’s questions. Fukumoto’s rapport with Gladys is much stronger, kinder, and less forceful, and it would have been nice to have them interact more than with Dunham. Fukumoto lets Gladys speak and only rarely directs her to an adjacent topic. Fukumoto does ask some follow-up questions, albeit much less than Dunham, but they are always more directly relevant to what Gladys is already talking about.

Another aspect, although perhaps much less important, is the decision to have Gladys in the corner of the room. I don’t think this affects the interview too much, as Gladys appears quite comfortable when speaking with Fukumoto, whom she looks at for the vast majority of the interview. But placing an interviewee in the corner of any room seems to be poor judgment. Police detectives, when interviewing a suspect, often employ the Reid technique, where one of its less controversial tactics is to place the interviewee in the corner of the room and have the interviewer block their path to the door. This, according to the technique’s advocates, makes the interviewee uncomfortable and more susceptible to mistakes and inconsistencies in their account. Whether these might have any tangible effects in a non-interrogatory interview, like Gladys, is unknown. Yet, placing an interviewee in the corner of the room nonetheless makes for a much less welcoming or comfortable environment. Jeremy Brecher, in How I Learned to Quit Worrying and Love Community History, outlines many of his initial struggles in his Oral history project in creating a welcoming atmosphere for interviewees. Brecher also notes how video recording often turned people away from an interviewer. These are important things to consider, and one of which physical distance between an interviewer and interviewee, hearing ability, tone of questions, or placement in the room, can all make a huge difference in the final product and quality of the interview.

Brecher, Jeremy. “How I Learned to Quit Worrying and Love Community History: A ‘Pet Outsiders’ Report on the Brass Workers History Project.” Radical History Review 28-30 (1984): 187–201.

Gladys Okada, “Rosie the Riveter WWII American Home Front Oral History Project” conducted by David Dunham and Candice Fukumoto in 2014, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=prlvOXwjlVI&t=5138s

Comments