Wednesday, February 28, 2018

12:00–12:50 PM | Paley Library Lecture Hall

Celine Jeong Kim, violin

Shannon Merlino, viola

Chen Chen, cello

Nam Hoang Nguyen, piano

Program

Richard Strauss, 1864–1949

Piano Quartet in C minor, Op. 13 (excerpts)

- Allegro

- Andante

Gabriel Fauré, 1845–1924

Piano Quartet No. 1 in C minor, Op. 15

- Allegro molto moderato

- Scherzo (Allegro vivo)

- Adagio

- Finale (Allegro molto)

Light refreshments served. Boyer recital credit given.

Nineteenth-century composers, Beethoven in particular, had a complex relationship with the key of C minor. In his monumental, five-volume Oxford History of Western Music, eminent music historian Richard Taruskin observes that Beethoven’s “C-minor mood” (a term coined by the late Joseph Kerman) has remained “a touchstone of music’s full potential within the European fine-art tradition.” The key is well-known for its mood swings, from abject moments of Beethoven’s “Pathétique” piano sonata, Op. 13, to ecstatic heights in the finale of his fifth symphony, Op. 67, where doom and gloom are irrevocably dispersed by electrifying jolts of C-major fanfares, scales, and batteries of thickly-textured chords. The influence of Beethoven’s C-minor symphony was so pronounced that few nineteenth-century composers dared approach this hallowed terrain in their symphonic works. Brahms bravely took up the task with his first symphony, his Op. 68, though pressure to follow in Beethoven’s footsteps drove him to labor on its movements for two decades: while the first known sketches date from 1854, it was not premiered until 1876.

The music of Brahms held enormous sway over a young Richard Strauss, who later characterized his early works as products of his Brahmsschwärmerei, his infatuation with Brahms. Many of the younger Strauss’s works were cast in a Brahmsian mold and bear influences of the elder composer’s penchant for dense textures and contrapuntal devices. And yet, they were far from derivative. Movements of the quartet heard on today’s program were penned in 1884 only a few years before Strauss embarked upon a new stylistic path with his celebrated tone poem Don Juan, Op. 20. His aptitude for constructing dramatic tension through manipulations of texture and harmony is evident from the first page of the Op. 13 quartet which begins in media res, dropping listeners into what seems like the middle or end of an idea rather than the beginning of one. This brief and understated reverie is upended, almost immediately, with an eruption of texture—marked fortissimo and appassionato—that propels the movement into its main idea and main key, C minor.

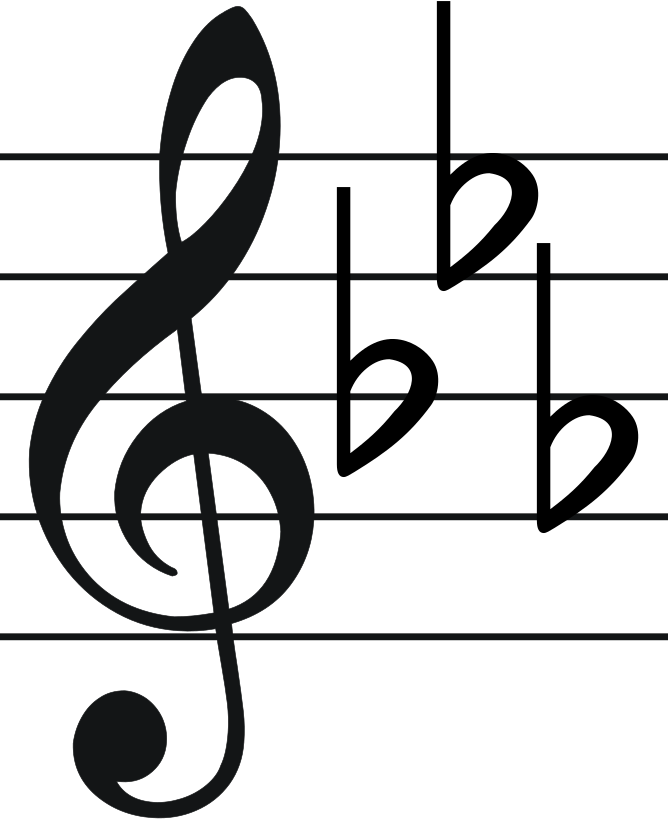

But Strauss’s C minor is restless: a cadence in the relative E-flat major (relative because the key signature of three flats “looks like” C minor) veers toward G-flat major without warning (a mediant relationship in theory-speak), which is then re-spelled enharmonically (the equivalent of a musical homonym) as F-sharp major. As before, this luminous moment is short-lived and storms back into minor—C-sharp minor, that is—with a violin melody fitted over galloping piano accompaniment. The angst is briefly dispelled in the latter half of the movement by rays of C major, but the minor mood generally prevails—one could easily mistake this for Brahms! Yet for all the resemblances to Strauss’s formative models, there is an emotional and impassioned intensity in both this and the third movement, a richly expressive “Andante,” that mark Strauss as a distinct voice. However, the most striking contrast between Strauss’s C minor and C major would have to wait another decade until he penned the opening of Also sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30, immortalized in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

As evidenced by the opening measures of his piano quartet, Op. 15, the “C-minor moods” of Gabriel Fauré were shaped by his exposure to the colors of modal harmonies gleaned from years of improvising plainchant accompaniments as an organist. His fondness for deft modulations and long, singing lines—one would expect nothing less from a respected composer of mélodie—once compelled Marcel Proust to characterize Fauré’s style as “dangerous intoxication”! The first movement of Op. 15, marked “Allegro molto moderato,” opens with a folklike melody played by the strings with a sturdy piano backbeat which makes for a rather jaunty effect; later, there are even a few jazzy episodes that seem to foreshadow Gershwin. The rhythmic energy of the first movement is carried into the second movement, a scherzo, whose nimble melody and pizzicato accompaniment are contrasted with expansive melodic arcs.

The third movement, marked by the increasing complexity of the piano part, begins with the same harmonic richness of the first two movements. These colors gradually fade, leaving the movement’s conclusion covered by a thick pall of C-minor. The effect is at once tragic, yet hauntingly beautiful. The fourth and final movement begins in the same low range where the previous movement left off, though now with a running C-minor arpeggiation reminiscent of the final movement of Beethoven’s “Pathétique” sonata. Like the trajectories of Beethoven’s fifth and Brahms’s first symphonies, the final movement of Fauré’s quintet offers a narrative progression of tragedy to triumph, of darkness to light that finally breaks through in the last few minutes with soaring strings buoyed by cascading arpeggiations in the piano part.

Though there is no direct evidence to suggest that Strauss and Fauré were as apprehensive about C minor as Brahms, their essays in this particular key nevertheless offer ways of hearing this nineteenth-century topos in their own respective ways. The relative ease with which they depart from the period’s formal and harmonic conventions also serve as markers of the new paths they would later explore, as well as the new directions and styles that appeared in this liminal space between the dusk of Romanticism and dawn of modernism.

Ensemble

Violinist Celine Jeong Kim graduated from Seoul National University of Music in Korea and has received awards in numerous competitions including the Busan Munhwa Broadcasting Music Competition, Mozart International Competition, and the Osaka International Music Competition. She has also appeared as a soloist with an international roster of orchestras including the Yongin Philharmonic Orchestra, Russian Symphony Orchestra, and Hankook Symphony Orchestra. Additionally, she participates frequently in the Moritzburg Festival (Germany) and Seoul International Music Festivals. While at Seoul National University, she was active in leading the Agnus Dei Ensemble in an effort to raise awareness for pediatric cancers. In 2013, she performed as Concertmaster of the World Bridge Symphony Orchestra with Deutsche Oper Berlin. Ms. Kim currently studies with Dr. Eduard Schmieder at Temple University’s Boyer College of Music and Dance.

Violinist Celine Jeong Kim graduated from Seoul National University of Music in Korea and has received awards in numerous competitions including the Busan Munhwa Broadcasting Music Competition, Mozart International Competition, and the Osaka International Music Competition. She has also appeared as a soloist with an international roster of orchestras including the Yongin Philharmonic Orchestra, Russian Symphony Orchestra, and Hankook Symphony Orchestra. Additionally, she participates frequently in the Moritzburg Festival (Germany) and Seoul International Music Festivals. While at Seoul National University, she was active in leading the Agnus Dei Ensemble in an effort to raise awareness for pediatric cancers. In 2013, she performed as Concertmaster of the World Bridge Symphony Orchestra with Deutsche Oper Berlin. Ms. Kim currently studies with Dr. Eduard Schmieder at Temple University’s Boyer College of Music and Dance.

Born and raised in the greater Philadelphia area, Shannon Merlino began violin studies at the age of nine, earning her Bachelor of Music degree in Violin Performance at Rutgers University as a student of Matthew Reichert and Lenuta Ciulei. She continued her violin studies as a scholarship student at Mannes College, earning a Master of Music degree while studying with Lewis Kaplan. Finally she completed doctoral coursework under Mikhail Kopelman at Rutgers University. After making the decision to focus primarily on viola, she began private studies with Kerri Ryan and is now in her second year of doctoral studies at Temple University. Her competition awards include second place in both the Miami String Quartet and South Orange Symphony competitions, and her solo credits include several appearances with the Lustig Dance Company. She has appeared in recitals as both soloist and chamber musician throughout the New York City metropolitan area, and maintains an active freelance performance career in the Philadelphia area as both modern and Baroque violist. Ms. Merlino has also given pre-concert talks on viola technique and pedagogy, most notably at the Library of Congress. Ms. Merlino performs on a viola by Clifford Hoing and a bow by Malcolm Taylor of W. E. Hill and Sons.

Born and raised in the greater Philadelphia area, Shannon Merlino began violin studies at the age of nine, earning her Bachelor of Music degree in Violin Performance at Rutgers University as a student of Matthew Reichert and Lenuta Ciulei. She continued her violin studies as a scholarship student at Mannes College, earning a Master of Music degree while studying with Lewis Kaplan. Finally she completed doctoral coursework under Mikhail Kopelman at Rutgers University. After making the decision to focus primarily on viola, she began private studies with Kerri Ryan and is now in her second year of doctoral studies at Temple University. Her competition awards include second place in both the Miami String Quartet and South Orange Symphony competitions, and her solo credits include several appearances with the Lustig Dance Company. She has appeared in recitals as both soloist and chamber musician throughout the New York City metropolitan area, and maintains an active freelance performance career in the Philadelphia area as both modern and Baroque violist. Ms. Merlino has also given pre-concert talks on viola technique and pedagogy, most notably at the Library of Congress. Ms. Merlino performs on a viola by Clifford Hoing and a bow by Malcolm Taylor of W. E. Hill and Sons.

Chen Chen is a doctoral cello student of Professor Jeffrey Solow at Temple University. She previously studied with Mark Kosower at the Cleveland Institute of Music where she received a Professional Studies Certificate and a Master’s and Bachelor’s degrees in performance. Past teachers include Merry Peckham, Richard Weiss, Natalia Pavlutskaya, Alexander Ivashkin, and Jin Zhang. Additionally, Chen has a foothold in the world of journalism: her interview with cellist Yo-Yo Ma was published in the spring 2014 issue of Mandarin Quarterly, Chicago edition. Chen has participated in many prestigious music programs with fellowships and scholarships, including the National Symphony Orchestra’s Summer Music Institute, the International Holland Music Sessions, Banff Music Centre for the Arts, and the Perlman Music Program Chamber Music Workshop. Chen has also participated in masterclasses with Itzhak Perlman, Steven Isserlis, Colin Carr, Raphael Wallfisch, Joel Krosnick, Andres Diaz, Reinhard Latzko, Lluis Claret, Maria Kliegel, Peter Wiley, and Alisa Weilerstein, as well as the Tokyo, Takács, Jupiter, Miró, St. John’s, London, Haydn and Chilingirian String Quartets. As cellist, chamber musician, Baroque cellist, and dancer, Chen has appeared in numerous renowned venues: Buckingham Palace, Wigmore Hall, LSO St. Luke’s, Windsor Castle, The Kennedy Center, Severance Hall, Verizon Hall, Alice Tully Hall, Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center, the Banff Centre, Cleveland Museum of Art, and the Cleveland Museum of Contemporary Art. Beyond her musical activities, she enjoys community engagement, hiking, reading, and writing. She is a frequent contributor to Mandarin Quarterly.

Chen Chen is a doctoral cello student of Professor Jeffrey Solow at Temple University. She previously studied with Mark Kosower at the Cleveland Institute of Music where she received a Professional Studies Certificate and a Master’s and Bachelor’s degrees in performance. Past teachers include Merry Peckham, Richard Weiss, Natalia Pavlutskaya, Alexander Ivashkin, and Jin Zhang. Additionally, Chen has a foothold in the world of journalism: her interview with cellist Yo-Yo Ma was published in the spring 2014 issue of Mandarin Quarterly, Chicago edition. Chen has participated in many prestigious music programs with fellowships and scholarships, including the National Symphony Orchestra’s Summer Music Institute, the International Holland Music Sessions, Banff Music Centre for the Arts, and the Perlman Music Program Chamber Music Workshop. Chen has also participated in masterclasses with Itzhak Perlman, Steven Isserlis, Colin Carr, Raphael Wallfisch, Joel Krosnick, Andres Diaz, Reinhard Latzko, Lluis Claret, Maria Kliegel, Peter Wiley, and Alisa Weilerstein, as well as the Tokyo, Takács, Jupiter, Miró, St. John’s, London, Haydn and Chilingirian String Quartets. As cellist, chamber musician, Baroque cellist, and dancer, Chen has appeared in numerous renowned venues: Buckingham Palace, Wigmore Hall, LSO St. Luke’s, Windsor Castle, The Kennedy Center, Severance Hall, Verizon Hall, Alice Tully Hall, Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center, the Banff Centre, Cleveland Museum of Art, and the Cleveland Museum of Contemporary Art. Beyond her musical activities, she enjoys community engagement, hiking, reading, and writing. She is a frequent contributor to Mandarin Quarterly.

Born in Hanoi, Vietnam, Nam Hoang Nguyen studied piano at Vietnam Academy of Music before matriculating at Temple University’s Boyer College of Music and Dance where he is presently a doctoral student in Piano Performance. His principal teachers have included Ha Thu Tran, Harvey Wedeen, and Ching-Yun Hu; he also studied collaborative piano with Lambert Orkis. Besides playing traditional piano repertoire, Nguyen enjoys playing chamber music, participating in different ensembles of various sizes, as well as studying early keyboard music. He also has interest in music research, and has lectured on Vietnamese music for piano.

Born in Hanoi, Vietnam, Nam Hoang Nguyen studied piano at Vietnam Academy of Music before matriculating at Temple University’s Boyer College of Music and Dance where he is presently a doctoral student in Piano Performance. His principal teachers have included Ha Thu Tran, Harvey Wedeen, and Ching-Yun Hu; he also studied collaborative piano with Lambert Orkis. Besides playing traditional piano repertoire, Nguyen enjoys playing chamber music, participating in different ensembles of various sizes, as well as studying early keyboard music. He also has interest in music research, and has lectured on Vietnamese music for piano.

References and Further Reading

Caballero, Carlo. Fauré and French Musical Aesthetics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Frisch, Walter. German Modernism: Music and the Arts. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2005.

Keller, James M. Chamber Music: A Listener’s Guide. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Kerman, Joseph. “Beethoven’s Minority.” In Write All These Down: Essays on Music, 217–237. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994.

Radice, Mark A. Chamber Music: An Essential History. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2012.

Smith, Peter H. “Intertextual Resonances: Tragic Expression, Dimensional Counterpoint, and the Great C-Minor Tradition.” In Expressive Forms in Brahms’s Instrumental Music: Structure and Meaning in His Werther Quartet, 234–284. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2005.

Taruskin, Richard. Music in the Nineteenth Century. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Trezise, Simon, ed. The Cambridge Companion to French Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Youmans, Charles, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Richard Strauss. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Chad Fothergill is a doctoral student in musicology at Temple University’s Boyer College of Music and Dance, and is the graduate assistant for the concert series, Beyond the Notes, at Temple University Libraries. He is also the editorial assistant for the journal Eighteenth-Century Music (Cambridge University Press). In addition to research and teaching, he remains active as an organist in solo, collaborative, and liturgical settings in the Philadelphia and New York City areas.

The series Beyond the Notes is supported by Temple University Libraries and Temple University’s Boyer College of Music and Dance.

One response to “C-Minor Moods: Chamber Music of Strauss and Fauré”

Hello! This is my first visit to your blog! We are a team of volunteers and starting a new initiative in a community in the same niche.

Your blog provided us useful information to work on. You have done a

wonderful job!