Cello Suites of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750)

Suite No. 1 in G major, BWV 1007

Suite No. 2 in D minor, BWV 1008

Suite No. 6 in D major, BWV 1012

Jeffrey Solow, cello

Wednesday, October 11, 2017 | 12:00–12:50 PM | Paley Library Lecture Hall

Light refreshments served. Boyer recital credit given.

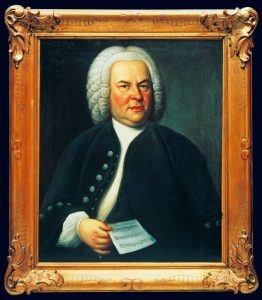

In the opening minutes of the 2013 documentary Bach: A Passionate Life, esteemed conductor Sir John Eliot Gardiner stands before a 1748 portrait of Bach by Elias Haussmann (1695–1774), one of the few authenticated images of the composer. Curiously enough, Haussmann’s portrait was sheltered for a brief time in Gardiner’s boyhood home, a country house safe from wartime bombing raids. Gazing upon the painting for the first time in decades, Gardiner notes two different faces of Bach: a potent, penetrating gaze under a furrowed brow seems to contradict the vivaciousness of the composer’s coquelicot lips and ruddy cheeks. Haussmann’s portrait of Bach—a duet between the consummate musical engineer and lover of fine tobacco and good brandy—is an apt entry into the character and complexity of the six cello suites, three of which will be performed by Jeffrey Solow on Wednesday, October 11, 2017 as part of Beyond the Notes, the Paley Library’s award-winning noontime concert series.

Numbered 1007–1012 in Wolfgang Schmieder’s Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis (BWV) thematic catalog, the six cello suites are renowned for their fusion of technical demands and vast expressive breadth. Like so much of his music, Bach filters received traditions—in this case, various dance styles that comprise the Baroque suite—through a master architect’s atelier. In his book Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician, Christoph Wolff observes that these suites not only “demonstrate Bach’s command of performing techniques but also his ability to bring into play, without even an accompanying bass part, dense counterpoint and refined harmony with distinctive and well-articulated rhythmic designs.” In short, there’s something for everyone: performer and listener, pedagogue and virtuoso, prince and peasant are invited into a realm of improvised oratory, foot-tapping jollity, and tender sighs.

And like much of Bach’s life, frustratingly little is known of the suites’ precise origins. Bach’s own manuscript is lost and four extant copies from both his lifetime and the later eighteenth century often disagree on matters of pitch, phrasing, and articulation. Nor is there consensus about the type of five-string instrument prescribed in Anna Magdalena Bach’s copy of the sixth suite in D major, which Solow will play on four strings. Did Bach write these movements for the violoncello piccolo or viola pomposa? In 2016, the Bärenreiter firm issued a new, two-volume edition of the cello suites, a compendium totaling more than 300 pages of commentary, music, and facsimile reproductions of early sources. Cellists are thus invited to see all the possibilities and make their own performance decisions for a given time, place, audience, acoustic, and even the type of instrument: no wonder the learned Bach seems to tease us with a slight, restrained smile from Haussmann’s portrait!

And like much of Bach’s life, frustratingly little is known of the suites’ precise origins. Bach’s own manuscript is lost and four extant copies from both his lifetime and the later eighteenth century often disagree on matters of pitch, phrasing, and articulation. Nor is there consensus about the type of five-string instrument prescribed in Anna Magdalena Bach’s copy of the sixth suite in D major, which Solow will play on four strings. Did Bach write these movements for the violoncello piccolo or viola pomposa? In 2016, the Bärenreiter firm issued a new, two-volume edition of the cello suites, a compendium totaling more than 300 pages of commentary, music, and facsimile reproductions of early sources. Cellists are thus invited to see all the possibilities and make their own performance decisions for a given time, place, audience, acoustic, and even the type of instrument: no wonder the learned Bach seems to tease us with a slight, restrained smile from Haussmann’s portrait!

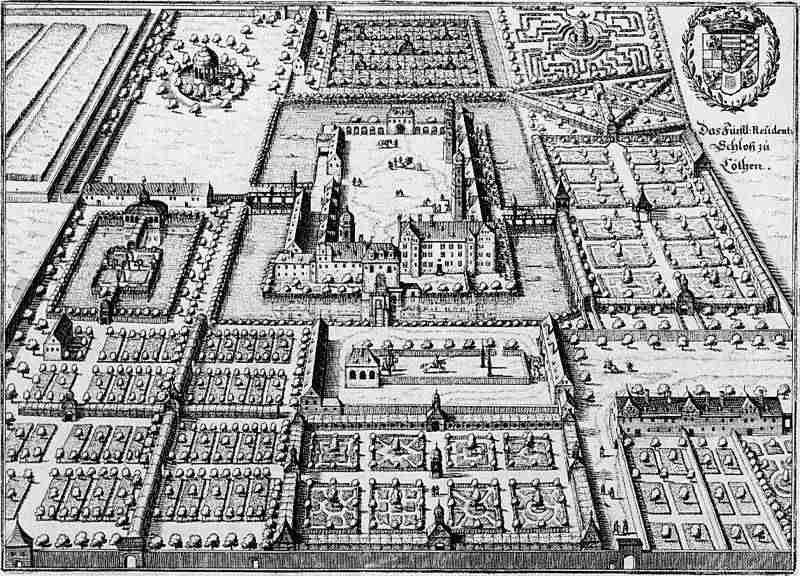

It’s likely that the cello suites were completed during Bach’s tenure as the Kapellmeister to Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen who, according to Bach, “both loved and knew music.” Bach’s employ, lasting from 1717 until 1723, was the impetus for some of his greatest instrumental hits including the solo violin partitas, “Brandenburg” concertos, and the first book of Well-Tempered Clavier preludes and fugues. Unlike his immediate preceding and subsequent positions in Weimar and Leipzig, Bach was not employed as a Lutheran organist or cantor. Instead, here in a Calvinist stronghold, he supplied instrumental music for the steady demand of courtly functions. The suites, partitas, and concertos are multi-movement works saturated with stylized dances that, since the seventeenth century, composers had penned “more for the ears” than “for the feet.”

Each of the six cello suites begins with a standard template, though the music is anything but standard or pedestrian: a prélude sets the tonal and emotive stage for four stock dances of the Baroque suite: a moderately-paced allemande, a “running” courante, a slow sarabande, and a lively gigue (or jig). Between the sarabande and gigue, Bach positioned so-called galanterie movements—menuets in the first and second suites, bourrées in the third and fourth, gavottes in the fifth and sixth—known for their lyricism and charm. From the expansive gestures of the first suite’s prélude to the jaunty swagger of the sixth suite’s gigue, Bach’s music radiates what journalist Eric Siblin calls a “refined aroma of music for connoisseurs.”

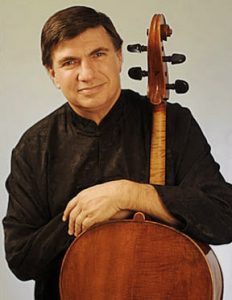

Jeffrey Solow’s impassioned and compelling playing has enthralled audiences throughout North America, Europe, Latin America, and Asia as a recitalist, soloist, chamber musician and teacher. Born and raised in Los Angeles, he studied with the distinguished cellist Gabor Rejto and earned a degree in Philosophy magna cum laude from UCLA while studying with and then assisting the legendary Gregor Piatigorsky.

Mr. Solow has performed more than 40 solo works with orchestras including the Los Angeles Philharmonic (also at the Hollywood Bowl), Japan Philharmonic, Prime Symphony Orchestra (Korea), VNOB (Hanoi), Seattle Symphony, Milwaukee Symphony, Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, and the American Symphony (with whom he also recorded) and he has been guest artist at many national and international chamber music festivals. His has recorded for the Columbia, New World, ABC, Centaur, Delos, Kleos, Laurel, Everest, and Telefunken labels and received two Grammy Award nominations.

In addition to performing, Mr. Solow’s editions of cello music are published by Breitkopf, Intenational Muaic Company, Peters, Latham Music, Elkan-Vogel, Henle Urtext, and Ovation Editions, and The Strad, Strings, and American String Teacher magazines have published his articles and reviews. Recognized as an authority on healthy and efficient cello playing, Jeffrey Solow is professor of cello at Temple University and has served as president of the Violoncello Society, Inc. of NY and of the American String Teachers Association.

Solow’s October 11 performance begins at 12:00 PM in the Paley Library lecture hall, 1210 West Berks Street. The program is free and open to the public.

References

Carrington, Jerome. Trills in the Bach Cello Suites: A Handbook for Performers. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009.

Little, Meredith, and Natalie Jenne. Dance and the Music of J. S. Bach, Expanded Edition. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2001.

Marshall, Robert L., and Traute M. Marshall. Exploring the World of J. S. Bach: A Traveler’s Guide. Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield: University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Siblin, Eric. The Cello Suites: J. S. Bach, Pablo Casals, and the Search for a Baroque Masterpiece. New York: Grove Press, 2009.

Wolff, Christoph. Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician. New York and London: W. W. Norton, 2000.

Chad Fothergill is a doctoral student in musicology at Temple University’s Boyer College of Music and Dance, and is the graduate assistant for the concert series, Beyond the Notes, at Temple University Libraries. He is also the editorial assistant for the journal Eighteenth-Century Music (Cambridge University Press). In addition to research and teaching, he remains active as an organist in solo, collaborative, and liturgical settings in the Philadelphia and New York City areas. He may be reached at chad.fothergill@temple.edu.

The series Beyond the Notes, is supported by Temple University Libraries and Temple University’s Boyer College of Music and Dance.