What significance does the concept of “home” have to people? I have been having a lot of floating, miscellaneous thoughts revolving around this question after finishing my current read, Breasts and Eggs by Mieko Kawakami, and learning about the gentrification and touristification of Mérida and the entire Yucatán Peninsula.

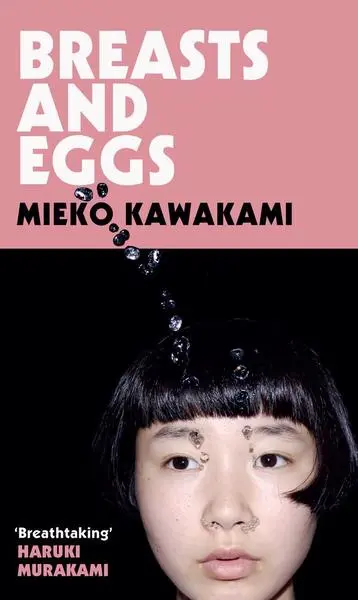

Breasts and Eggs is not a book about tourism. It is a fiction novel highlighting the experiences of three generations of Japanese women. The main character, Natsuko, tells this story in her 30s, following the death of her mom and grandma, her two caregivers who passed away when she was 12. Although tourism is not the focus, it creeps into the plot in obvious ways.

Here in Mérida, we often have discourse about the material, cultural, and economic consequences of touristification and how they manifest over generations, but after finishing Breasts and Eggs, I realize the importance of also highlighting the emotional toll gentrification alone takes on individuals personally affected. In the story, Natsuko leaves her current apartment in Tokyo to visit her hometown she grew up in by the sea called Osaka. Upon her return, she reminisces on her limited time she had with her mother in that place and mentions how, “Everything about the street, besides the udon shop, had changed. Now it was one long row of gift shops for the tourists, ” (Kawakami 388). She continues walking around, in disbelief of how only pockets of what she once knew remained; she wonders how her mother must’ve felt the first time she moved to Osaka, and is disheartened because she can never really know. Trying to find their old apartment, Natsuko constantly reconsiders and thinks to herself, “Why was I obsessing over this? There was nothing monumental about checking out the neighborhood you used to live in. So why was I in turmoil?” (Kawakami 390). She finally gets to the doorstep of her old home and writes “If I could open up this door, maybe I would find them… if I could open this door, maybe I would see my favorite sweatshirt and my bookbag and my doll, where we laughed and where we slept…” (Kawakami 394). Places hold memories, and Natsuko grapples with this fact throughout the story while she struggles to remember her childhood and mother in a town she once knew intimately. Of course as time progresses change is inevitable and always has been, but gentrification and touristification don’t simply cause change, they transform locations– and at a rapid rate at that. A place that once served as a home for Natsuko and her family now serves as a playground for tourists… and this breaks her heart! It can be as simple as that. Yes gentrification is terrible because it displaces families, increases prices for locals, turns a place once built for authentic life into one for performance, etc., but gentrification and touristification also destroy personal memories. They rewrite culture and history, and it is also vital to understand the ways in which they rewrite personal connections.

Although mental turmoil is largely caused by the material consequences of gentrification, I’d argue that the mental turmoil generated by gentrification alone is enough to resent and protest it. I wonder what Mérida looked like 50, even 10 years ago, and how the residents may have struggled and are currently struggling to hold onto their memories and connection to this area. Last month, my mom visited Iran, her country of origin, for the first time in 20 years. She told me she didn’t recognize the city she grew up in: “It’s completely different. That place doesn’t exist anymore, ” she told me. It was as if she was a stranger in her own home, and I imagine there are a myriad of people in the Yucatán who feel similarly.

It is hard to navigate how to be mindful of my place in the gentrification and touristification of this area even though I know there are larger structures at play that have allowed it to become this way– and I will spend my life trying to protest those as well. With that being said, I also urge everyone in this class, myself included, to carry this line of thinking back to Temple, a university that has displaced many predominantly black and low-income individuals and families. Mérida is not our playground and neither is North Philadelphia. We should be cognizant of the difference between our living off campus and the families that grew up there and have called that place home. Everyone deserves to have a home to return to.