Philadelphia is a city full of historical figures and the legacies they left behind. There are some big names, like Benjamin Franklin, however, there are many important people who go unnoticed. In North Philly, a name that people may recognize is Cecil B. Moore, a lawyer and civil rights activist, who helped fight for the civil rights of the black working class and students.

Early Life & Activism

Cecil B. Moore was born on April 2, 1915, in Dryfork Hollow, West Virginia. He attended high school in Kentucky, enrolled in Bluefield College in West Virginia, and became a traveling insurance salesperson. Eventually, he became a sergeant and “was one of the Montford Point Marines, who battled racism and segregation to become the first Black men in the corps who were allowed to carry weapons and serve on the front lines” (Oputu & Eiser). After many years of travel, Moore ended up settling down and enrolling in Temple University’s Beasley School of Law in Philadelphia in 1947 (Borden).

One of his most recognized contributions to the North Philadelphia area was his involvement with the NAACP, The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Moore often found himself at odds with older members and activists due to differences in activism styles. With his military background, he was more assertive and confrontational, whereas older activists took calm and conversational positions. Because of the opposition between them, “He criticized the older generation of NAACP advocates for failing to acknowledge issues affecting the working man and lower-class black community” (Costello).

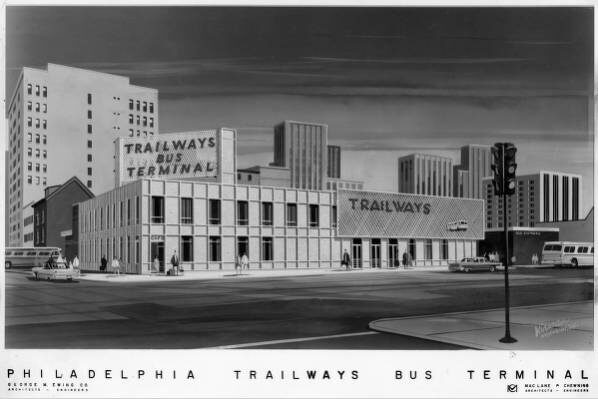

Moore was very involved in desegregating construction sites and labor unions, as well as other workplaces around Philadelphia. He protested and picketed at the Greyhound as well as the U.S. Postal service, for they had held racial bias against the black working class (Biography.com). In 1963, he picketed at the new Municipal Services Building construction site on May 11th (this would last for many weeks), a local school construction site from June to July, and finally, in December, he picketed at the Trailways Bus Terminal (Costello). Although these efforts weren’t as successful as intended, it ultimately increased the amount of black employees all over Philadelphia.

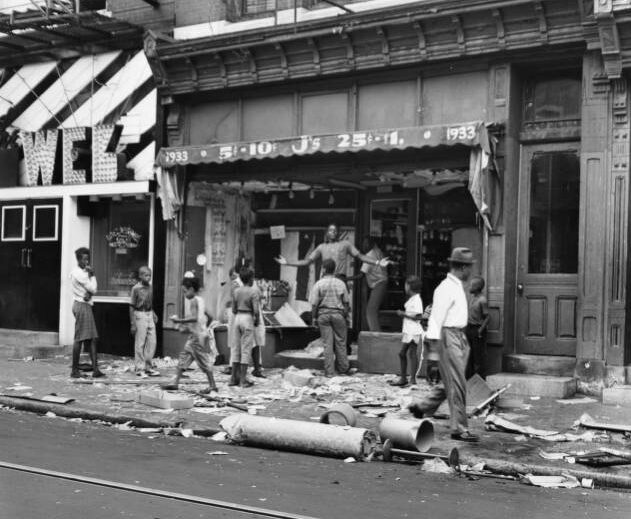

The 1964 Columbia Avenue Riots

He was also involved in the 1964 Philadelphia Race Riot, otherwise known as the Columbia Avenue Riots. On August 28, 1964, two officers responding to a domestic dispute call from 22nd Street and Columbia Avenue turned violent when misinformation spread that a black pregnant woman was beaten by white officers (Candeaux). Hundreds of people gathered in the street and began to throw objects and beat the officers. This event then evoked a riot that would last a couple of days. When Moore had heard what was happening, he went to the scene and urged rioters to return to their homes (Kativa).

“The grim result of three days of rioting was 341 injuries, more than 700 arrested, and at least one death… More than 700 buildings were damaged… North Philadelphia has never entirely recovered” (Woodham). If Moore had not told people to go home, the amount of irreversible damage to the city would have been greater, and more people may have gotten killed, injured, or arrested. Columbia Avenue was eventually renamed Cecil B. Moore Avenue in 1987 to honor him.

The Desegregation of Girard College

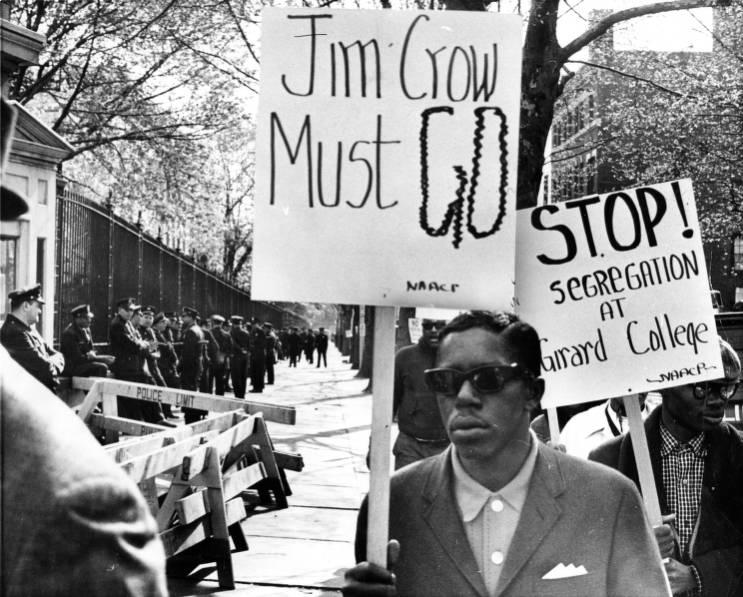

“Protestors outside of Girard College call for de-segregation” | Image linked to Voices of the Civil Rights Movement’s YouTube Video

Girard college was an all-white boys school in a predominantly black neighborhood, even after Brown vs. Board of Education had been settled in 1954. After being reelected as NAACP President in 1965, Moore made a promise to integrate the college after witnessing the injustice and studying the mission of Raymond Pace Alexander, who had been fighting this same battle for ten years prior. The difference between the men’s approaches is that Alexander battled through the court system, whereas Moore brought the fight directly to the streets of Philly (Kativa, pp. 1-6).

Because of Moore’s strong stance, he began the NCAAP’s protest at the college on May 1st, 1965, with 20 picketers and 800 police officers (Kativa). He “organized daily picketing outside of Girard in order to attract media attention both for and against the movement and to gain the attention of public officials and pressure them into action” (Schickling). For seven and a half months, Moore protested outside of the school, the crowd consisting majorly of the black middle-class. The attention for the protest had grown so much that over the summer, important civil rights leaders had joined, like the National NAACP President, Roy Wilkins, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (Kativa). The case eventually made its way through the court, and Girard College was desegregated on May 20th, 1968.

A Long Lasting Legacy

Almost forty two years after his death, Valerie Harrison, the Senior Advisor for Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, announced on September 16th, 2020, that there would be a one million dollar anti-racist initiative implemented to combat racism not only Temple University, but all around Philadelphia. As a part of this initiative, they announced the creation of the Cecil B. Moore Scholars Program. The school is partnered with Steppingstone Scholars, a non-profit dedicated to helping low-income students of Philadelphia transition into college and even the workforce. The program is designed to give public or charter school students in North Philadelphia access to an equal education, which is something that Moore fought for (Krotzer pp. 1-6).

The university offers a free dual enrollment course to North Philadelphia students in the spring of their senior year. Upon evaluation, the college chooses around 25 students to move on to a summer bridge program, designed to help students academically and socially transition into life at postsecondary schools. Once the students are enrolled full time, they receive academic advising and support from both the school and Steppingstone Scholars. Since the program was created within the last four years, it could inspire other programs and initiatives to form in schools across Philadelphia (Krotzer pp. 9-13)

Cecil B. Moore’s passion and drive to give the black citizens of Philadelphia a voice changed the history of the city forever. If Moore hadn’t advocated for the desegregation of workplaces and education, things like the Scholars Program may have never existed, and residents from this area would have less access to educational and career opportunities.