Welcome to the city! (Not really)

In the city of Philadelphia, sports are taken extremely seriously. Philadelphians go hard. They refuse to let up. They take pride in the city and teams. Primarily, though, they are notorious for being some of the most poorly-mannered fans in the major sports leagues. Being crude and hostile is what gives Philly fans their fidelity. Class isn’t needed in order to reflect devotion towards a team or player. It boils down to passion; it’s what flows through Philadelphians’ veins. They don’t take talk lightly since they have been, and continue to be, looked down upon. Choosing to embody the underdog mentality is something they will forever take pride in.

Some may consider being a Philadelphia sports fan, or simply being from here, the worst. With the tainted reputation, it’s difficult to prove others wrong about the city. Yet, the inferiority is what makes the residents and fans that much tougher. For what seems like forever, and still to this day, there is a constant desire to show the rest of the sports world that Philly should be recognized and respected since they are the ultimate underdog. Recently, the rest of America has gotten that message, which is something that fans will not let anyone live down. Though they can be rough sometimes, it all comes from love. After all, it is the City of Brotherly Love.

Some may consider being a Philadelphia sports fan, or simply being from here, the worst. With the tainted reputation, it’s difficult to prove others wrong about the city. Yet, the inferiority is what makes the residents and fans that much tougher. For what seems like forever, and still to this day, there is a constant desire to show the rest of the sports world that Philly should be recognized and respected since they are the ultimate underdog. Recently, the rest of America has gotten that message, which is something that fans will not let anyone live down. Though they can be rough sometimes, it all comes from love. After all, it is the City of Brotherly Love.

Philly Loves You Too

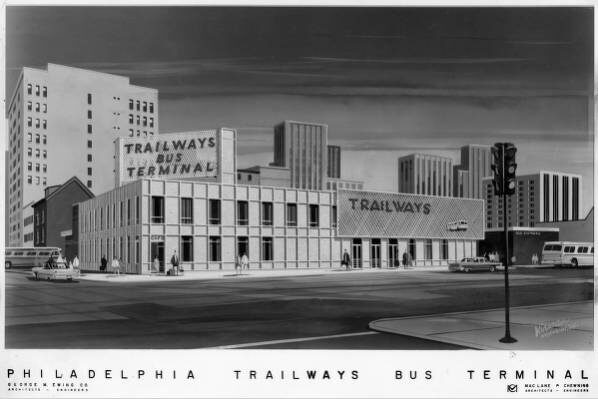

A plain skyline and a cracked bell is what makes this run-of-the-mill looking city. In Philly, people don’t want the attention drawn to them. It is a working class town with generations of families who have lived in and near the city. They take pride in being tough, working hard, and refusing to take shortcuts. This makes most of them reserved people, adding to the antisocial characteristic. Sure, one can visit, but they will not be warmly welcomed.

Others see Philadelphia, “…as a uniquely cold and unwelcoming place” (Dilworth, 2006). Even back in 1798, when Abigail Adams was obligated to reside in the city, she wrote to her sister, “‘These Philadelphians are a strange set of people…They have the least feeling of real genuine politeness of any people with whom I am acquainted’” (Dilworth, 2006). Proving that not much has changed since. The thing is, there’s no explaining these values and behaviors that inhabit the glorious urban landscape. The best and only way is to remember that everything is practically the opposite of common decency. For instance, “Anger is a way to express caring…[it] can only be called an angry love. It is loyal, it endures–but it has spikes and edges” (Satullo, 2011). When cheering for a sports team, make sure to, “…[cheer] against the home team” since it is, “…a time-honored tradition in Philadelphia” (Dilworth, 2006). It may feel weird, but it’s correct.

The Mentality of a Philly Fan

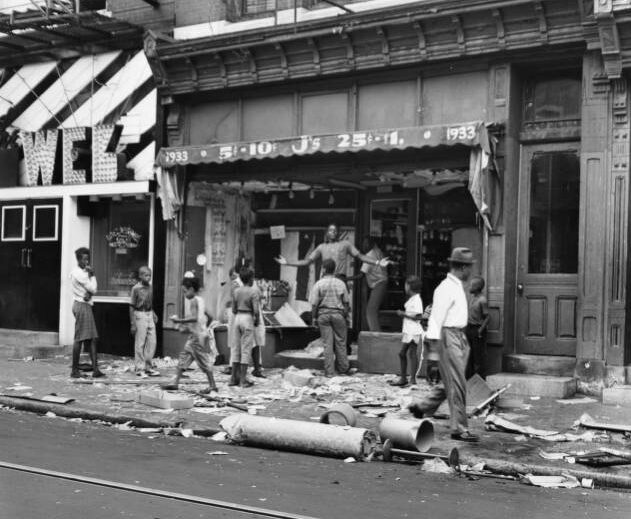

Out of all the teams on the East coast, Philadelphia tended to be the worst performing city. Not only were the cities bigger and flashier, their teams were better. This left Philly in the dust. Always catching up and always having something to prove. This stems from the determination of striving to be better than the competition. The city was always underestimated in every capacity and others would never even look this way. Philadelphians continue to make the choice to embrace the grit and dedication of the underdog mentality and express it loudly to prove that they want it more than anyone else.

The underdog mentality has always been present in the city and its culture. However, more recently, it dominated its way into Philly’s sports. In the 2017 NFL season, Carson Wentz suffered a season ending injury in the playoffs. This forced the backup quarterback to lead them through the last half of the season. No one thought they would make it. When it came time to play the Falcons, Chris Long and Jason Kelce brought dog masks to the game to represent them being underdogs. After the win, they walked off the field wearing them to demonstrate that they were never favored to get this far. From there on, the team would wear the masks on the bench and when walking off the field after a win. Eagles fans loved the skepticism that surrounded the team making it that far and getting the ring. The struggle, grit, and hard work it took to get to that position directly represented what the city of Philadelphia is about.

Infamous Stories

In December of 1968, a snowstorm that dumped copious amounts of precipitation on the city left Franklin Field filled with snow for Sunday’s football game. The team was facing a 2-11 record, leaving fans hopeful for a loss in order to receive decent picks in the upcoming draft. To fans’ surprise, they took the lead at the start of the game. This only increased the upheaval. Halftime came, the game was tied, and the original Santa Claus that was supposed to perform didn’t show due to the weather. This caused the Eagles staff to act in a panic until they found Frank Olivo, who was coincidentally dressed in a Santa costume. The staff, “…frantically approached him and begged him to be their halftime Santa” (Frank 2020). He agreed, and took on the job. Upon stepping onto the field, he was first met with boos. Boos turned into snowballs, snowballs turned into beer bottles, beer bottles turned into hoagies. “‘They were throwing anything they could get their hands on’” (Frank, 2020). Trying to lift the spirit proved to not be the best idea. Eagles fans were tired of defending their team while consistently being the worst in the league. No matter how bad the team kept becoming, one thing they would never do, though, is switch sides.

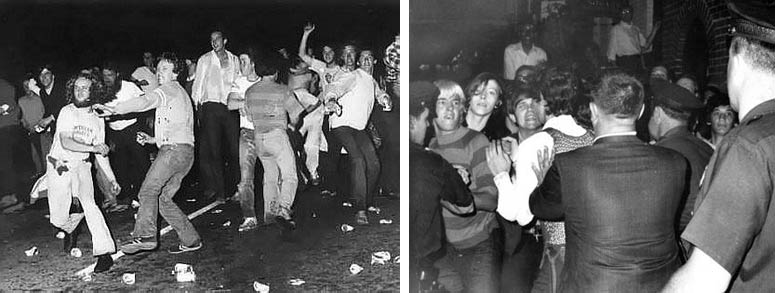

Broad Street Celebrations

In February of 2018, I attended the Eagles Super Bowl parade with my family. What a day–and experience–that was. It seems like forever ago. We got up around five in the morning to catch the train down into Center City. Philadelphians were doing what they do best: climbing random objects. All of the statues near and around the art museum were occupied by fans. Every tree had at least one person in it. The excitement was unimaginable. It felt like it was continuously building up and about to explode. It erupted once the buses with the players came by. Finally bringing home a Super Bowl ring after presumably being the worst team in the league was unbelievable. We stayed to hear Kelce’s speech. It was absolutely invigorating. He listed off every player and criticism that was tied to them. He explained how not only the team, but the staff and coaches simply wanted it more than any other team because of the odds that were stacked against them. He drew from the quote displayed in the locker room and said that underdogs were hungry dogs, and “Hungry dogs run faster”. To wrap it up, he started to sing, “No one likes us. No one likes us. No one likes us, we don’t care. We’re from Philly, F–ing Philly. No one likes us, we don’t care!” It’s understood that there are no positive feelings towards us, and we could not care less. The passion that Kelce spoke with that day, defending the entire city, was remarkable.

Remember the Name

Some may consider being a Philadelphia sports fan, or simply being from here, the worst. With the tainted reputation, it’s difficult to prove others wrong about the city. Yet, the inferiority is what makes the residents and fans that much tougher. For what seems like forever, and still to this day, there is a constant desire to show the rest of the sports world that Philly should be recognized and respected since they are the ultimate underdog. Recently, the rest of America has gotten that message, which is something that fans will not let anyone live down. Though they can be rough sometimes, it all comes from love. After all, it is the City of Brotherly Love.