The theme of dancing about architecture abides in our oral history readings. Too, the theme of reconstructing memory and all its organic challenges. Perhaps a dozen years ago, I visited Rowan Oak in Oxford, MS, William Faulkner’s home and now a museum. I draw on that and other experiences in interpreting some of these themes.

Abrams says, “it is more realistic to accept that there can only be a semblance of similarity—a verisimilitude—between a narrative as told and a narrative written down; something happens in the process of speech being translated into text.” (p. 13). Something does indeed happen in the process of writing down what is said. I have often heard the phrase that there are three sides to any story: what you said, what they said, and—somewhere in the middle—the truth. Bearing in mind a professor of history’s recent assertion (Dr. Bruggeman, guest speaking in this class) that the historian’s goal is to, “provide the best approximation of the truth,” it may be helpful, from a theoretical perspective, to parse out the layers between the truth and the verisimilitude, that being, the transcript. But then again, it may be too time-consuming to do so. Consider that there is, perhaps, a “truth” somewhere in the middle. This may imply the existence of the absolute truth, which may require a reconstruction of the entire history of everything, so we shall leave that aside. Instead, let us constrain ourselves to an interpretive reconstruction of your story and their story and, between the two, the possible reconstruction of the best approximation of the truth.

The layers of the truth, then, as I count them in chronological order, are as follows. First, something happened that created a memory, already reconstructed in the mind of the historian as being worth the effort of research, that should be further researched. Second, there is research done by the historian in the interest of becoming a fully capable interviewer, which further shapes that memory in the mind of the historian. Third, the historian researches possible interviewees. Fourth, there are the questions composed by the historian that may be influenced through interaction with interviewees, further changing and shaping the project. Fifth, there is the setting of the interview. Besides the simple, bare necessities of a quiet space and adequate audio or audio and visual recording equipment, the interview may be set in places that the interviewer believes may contribute to enhancing the ability of the interviewee to reconstruct their memory, which may be constrained or enabled by time, availability, funding, etc. (transporting interviewees to an overseas base and interviewing beneath a work of art have both been mentioned in class). Sixth, at last, is the interviewee’s reaction to questions within the interview’s setting. Seventh is the historian’s reaction to the interviewee’s response that may bring up additional questions or ways in which the interviewer asks questions (oh, what a tangled web we weave!), eighth is the interviewee’s reaction to the historian’s reaction . . .*

Perhaps this exercise will serve to further complicate the issue. Regardless, there are many steps taken before a transcript is made, and nothing springs to mind quite so neatly (neatly in example but messy in practice) as my experience at Rowan Oak.

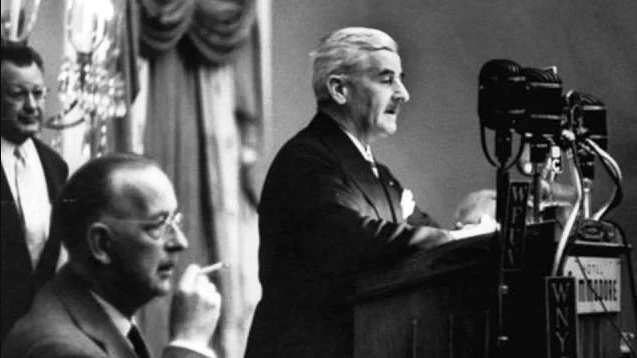

Many years ago, I visited William Faulkner’s home in Mississippi. During my visit, I had the opportunity to listen to an exhibit featuring Faulkner’s 1950 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech. Mostly alone in the museum, I listened to it many times before leaving. Re-listening to the speech in conjunction with its official transcript this week, I was struck by a profound realization: “that’s not right!” The speech I remember hearing, along with its profound emotional import, was not the speech I heard this week.

This brings us to the second point of this post, that “oral history is a three-way conversation: the interviewee engages in a conversation with his or herself, with the interviewer and with culture” (p. 76). If asked to recount Faulkner’s speech, I could do so. However, I realize that my recounting differs from the speech I heard online earlier this week. What is to be made of this? Perhaps that is the central question to the theory of oral history.

Lynn Roberts states, “Experimental research has demonstrated that it is quite easy to induce subjects to make false reports. . . . people are very susceptible to suggestion” (p. 85). This calls into question the nature of the interviewer in the process of making oral history. Certainly, many things shaped my reconstruction of the memory of listening to Faulkner’s speech in Rowan Oak. That speech was re-listened to many times mentally between then and my re-listening to the original (I questioned if the renditions currently online were not altered somehow).

How can we minimize confirmation bias in our interviews? How can we neutralize (in one sense–notwithstanding the importance of “taking sides”) the subjective views of the interviewer? How would my questions have changed from a dozen years ago to now if I interviewed subjects on their experience in listening to that speech? Naturally, a broad reading of numerous sources prior to the interview itself can lend itself to an air of impartiality. On the other hand, would not a cohesive view of the project lend itself to preconceived notions of the truth and, by extension, the development of attitudes and questions in the interest of gaining proof for that truth in an interview?

Lastly, as in the book, let us discuss trauma. Lynn Abrams’ Oral History Theory deals with trauma in the subject of an interview, which is vitally important to the ethical conduct of oral history. Indeed, the contents of this chapter would have been a wonderful aid in many interviews in my professional conduct as an investigator. However, I would add to Roberts’ previous assertion that, “oral history is a three-way interview.” Not only does the interviewee converse with themselves during the interview, but so does the interviewer. During a recent project, I found myself inexplicably challenged in asking particular questions of a subject regarding the death of a loved one (essential questions that would have greatly aided my project!). After much rumination on the possibility that I may have experienced a reversed power dynamic of feeling unable to ask particular questions due to the subject’s position of power in an institution relative to mine, I realized the possibility of an additional concern. I had personal questions for the subject that were also quite personal to me, and, therefore, I didn’t ask them of the subject because I would rather not have them asked of myself.

This is an extreme example of an interviewer’s inability to ask important questions and, admittedly, one that would have had less impact with prior realization and preparation. Regardless, I believe this raises an important point, although one that, at its barest personal level, is anything but self-evident prior to its crystallization: our ability to identify personal trauma (and bias) has a direct impact on our ability to conduct an interview (I am applying the ideas of personal bias and trauma in the sense that they may be invisible to the interviewer until a crystallizing moment). What is to be made of this? Perhaps that is a tangential question to the practice of oral history. **

Roberts, Lynn. Oral History Theory. 2nd Edition. Routledge, 2016.

*I am brought back to my experience leading a Military Working Dog Detachment and the challenges faced by working dog handlers in training their dogs (collectively referred to as MWD teams). MWD teams may go through months of training, showing steady progression, only to fail during certification. Often, certification failure is attributed to the handler’s nervousness under the pressure of certification. Indeed, the working dog’s strength is more in their sense of smell than in the strength of their jaw, and the dog can smell their handler’s stress hormones coming “down the leash,” leading them to adopt a nervous and excitable state. The dogs become reactionary. Sometimes, however, the team’s failure is attributed to the dog chasing a flock of geese, because that’s what a dog might do when a pond-full of geese flies away. MWD teams achieving success in certification are often given the backhanded but good-humored compliment, “dog did good.” The back-handedness of the compliment, naturally, references the dog’s success despite the handler (and it may have cultural implications about the military and its use of modes of reinforcement). Perhaps there is a parallel to the interviewer’s role in oral history. Sometimes, an interview may go well despite the interviewer’s powerful ability to disrupt. Other times, a flock of geese might be flying away.

**My apologies to my professor for a post that is over twice the required length. I had four more sections from the book that I wanted to cover and elected to exclude them from this already long-winded post. Good book! Happy Wednesday!