Between October 1977 and May 1981, the Louis B. Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky conducted, as part of an oral history project on Robert Penn Warren, forty-three interviews of Warren and his friends, family, and colleagues.1 The Louis B. Nunn Center processed, transcribed, archived, and published the project over the course of the next twenty years. In the early 1990s, my mother participated in this project, working in the University of Kentucky library’s collection development under the direction of Terry Birdwhistell, an archivist and oral historian. As my mother fondly relates, a student assistant came to her with the startling observation that, as the student discovered during her transcribing of one of Penn’s interviews, he referred to somebody as a “rack of turd.” Whatever was to be done about including such vulgar (and so very odd) language in the transcription? Who would have thought that a Pulitzer-winning author would be so crass? In assisting the student with the transcription, my mother realized Robert Penn Warren actually said raconteur. As the story goes, Warren had been imbibing a glass of “iced tea” that had the peculiar effect of reducing his ability to enunciate as the interview went on. Mirthful as the story is, it illustrates a number of challenges one might encounter in the making of oral history.

The practice of oral history introduces factors not always found in other methods or practices. Interviews offer a space for human intimacy absent from written records in an archive. Indeed, Allan Nevins provides many examples of how a good oral historian can build a closer approximation of the truth than could the subject themselves without an “earnest, courageous interviewer.”2 Allessandro Portelli voices a parallel assertion that, to take full advantage of the uniquely human elements of oral history, the interviewer should pay no mind to remaining neutral.3 Taking sides, then, may be yet another ad hoc question with an ad hoc answer.4 Nevins and his colleagues expound at length on the challenges of oral history, one of which is to understand not what somebody said but the way they said it. Central to the story of the raconteur is a student mishearing Warren’s turn of phrase while transcribing an interview, and it suggests deeper insight than a simple error of the ear.

Allessandro Portelli states, in plain language, “Oral sources are oral sources.”5 A portion of his argument may be summarized, in a parallel fashion, by a phrase widely attributed to several different origins: “writing about music is like dancing about architecture.” Is transcribed oral history just “dancing about architecture”? Portelli stops short of ascribing quite such negativity, though he details the many ways in which a transcribed account loses significant portions of its value, in no small part due to the structure of the written word that is necessarily imposed upon the oral source in the process of transcription. Similarly, Halpern asserts that “remembering should be seen as a process of historical interpretation”6 and that oral sources are unique in their ability to shape interpretation by the very nature of being oral.

Perhaps, then, transcribing oral history is akin to describing a piece of music. Despite this, the oral historian of 2025 and beyond has a far more comprehensive toolkit for the making of oral history than that available to historians of the ’90s. While I accept Portelli’s assertion that the oral source reigns supreme in oral history, I take the liberty of critiquing his claim that the oral historian should take no further efforts to find better methods of transcription.7 As large-language, generative, and other AI models progress, perhaps historians will find their use in the processing and dissemination of history. Much in the same way that an archaeologist, a biologist, and a forensic artist may digitally recreate a face from a bare skull, might the oral historian, with enough data and collaboration, recreate the oral from the written word? Would such an endeavor be more Hollywood than history? Perhaps we will find out.

As we draw to a conclusion, I harken back to the idea that the “earnest, courageous interviewer” can better approximate the truth than the autobiographer. In a cursory sense, this is true. If one takes part in an event worthy of a story, say, at dinner with friends, one will gladly interject, “Oh! Don’t forget…” as your friend regales the crowd with the story. Is this the role of the oral historian? No, for the necessity of an earnest, courageous interviewer implies the existence of struggle and danger. Where, in the making of oral history, do we find the struggle and danger that necessitate courage?

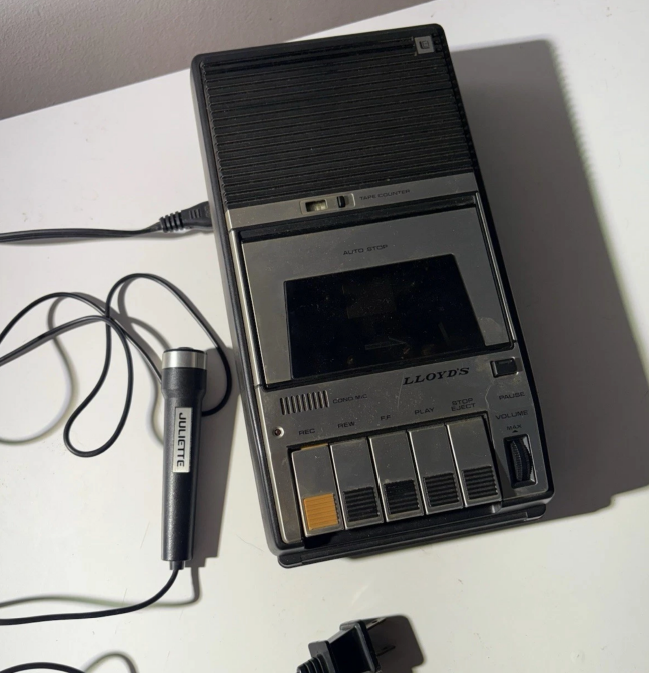

Image: Ebay listing, 1970s Lloyd’s Compact Cassette Tape Counter Recorder Model V117 Vintage Player | eBay

- Robert Penn Warren Oral History Project · SPOKEdb ↩︎

- Dunaway, David, K, Willa K. Baum, eds., Oral History: An Interdisciplinary Anthology. AltaMira Press, 1996, 37. ↩︎

- Portelli, Alessandro, The Death of Luigi Trastulli, and Other Stories: Form and Meaning in Oral History. State University of New York Press, 1991, 54. ↩︎

- Dunaway, David, K, Willa K. Baum, eds., Oral History: An Interdisciplinary Anthology. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press, 1996, 35. ↩︎

- Portelli, Alessandro, The Death of Luigi Trastulli, and Other Stories: Form and Meaning in Oral History. State University of New York Press, 1991, 46. ↩︎

- Halpern, Rick. “Oral History and Labor History: A Historiographic Assessment after Twenty-FiveYears.” The Journal of American History 85, no. 2 (1998): 598. ↩︎

- Portelli, Alessandro, The Death of Luigi Trastulli, and Other Stories: Form and Meaning in Oral History. State University of New York Press, 1991, 46. ↩︎

*Despite Arnold Schwarzenegger’s starring role in the 1984 blockbuster “Terminator,” I believe we can agree that “AI” in the ’90s was more “fi” than “sci” to the point that “AI” was of no consideration in Portelli’s argument. Perhaps the modern oral historian should not search for the better, faster, or stronger way to transcribe oral history, but the new way. “New” technology, in this case, comprises the advancements that are fundamentally different from those of the ’90s, i.e., not a faster horse, but a car. What, then, is our horse?