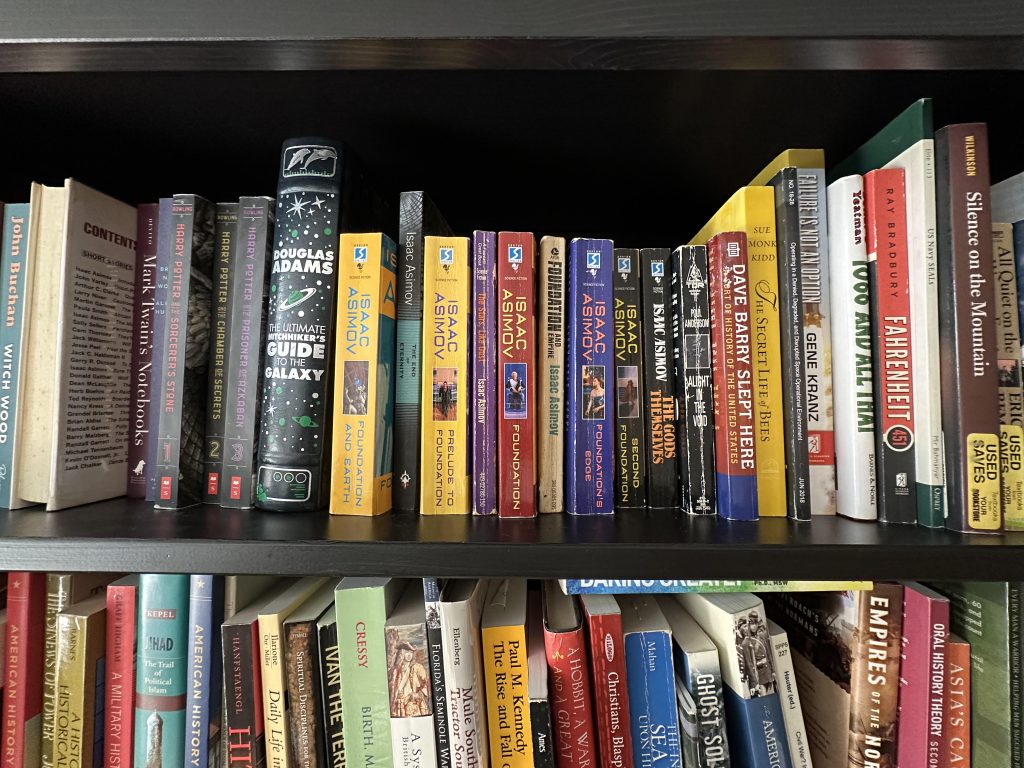

The Sci-Fi genre has, since my youth, played a prominent role in my extracurricular reading. I took a particular liking to Isaac Asimov’s works, and I often find myself rereading his Foundation series, a major plot point of which is the concept of psychohistory, co-developed by the character Hari Seldon. This fictional study, not to be confused with the very real interdisciplinary study that goes by the same name, proffers the idea that if you study a large enough group of people–say, an entire galaxy’s worth–you can predict the future actions of those people. As the centuries pass, the reader finds that (spoiler alert!) Seldon’s predictions fail before the course of history is righted by a secret foundation of psychohistorians, after which that same secret foundation is supplanted by another (and likewise secret) society. As we deal with the complexity of the study and making of oral history, perhaps we can find a few helpful parallels and, like psychohistory, our oral history project will transform from something that may be messy to one that, rather than messy, is complex.

Donald Ritchie’s Doing Oral History provides an example of an oral history project conducted by faculty at Indiana University into the cause of declining birth rates in Russia after Stalin’s abortion ban. A fellow member of the faculty critiqued the study, and “yet even the dissenter agreed that oral sources, ‘may not tell you much about what Stalin was doing, but they were terribly useful in telling you about people’s minds.’”1 Taken at face value, this comment indicates that oral history can be useful for something, but perhaps not the thing you set out to do or, perhaps, what you should be doing. There is also an air of finality to the critique, as if once the (at least at the time) more conventional history has been produced, other approaches will, if not detract from the established narrative, at least add noise that would be better left disregarded.

The idea that oral history may be useful but just not in the way a project sets out to may be true at some level. A historian cannot interrogate the archive until the archive is available, much like a psychohistorian must study the sum of humanity to reach a precise conclusion. Central to the practice of oral history is the making of the archive, so it follows that there is no guarantee that the conclusion of a project produces an archive that is complete with regards to the project’s intended scope. To clarify, I do not suggest writing an oral history research proposal outlining a plan to ask every single person every possible question (though that would be quite humorous). This brings up a similar challenge to that posed by the dissenting faculty member at Indiana University in that the archive, being in our case firsthand accounts, may not only be incomplete but inaccurate. However, inaccuracy implies that we both know what the target is and that it has already been hit. Along these lines, I am interested to read Alistair Thomson’s work mentioned in The Manual for Oral History regarding the understanding of subjectivity in oral history accounts.2

Going back to last semester’s Managing History course (of which I was not a part), we can see students’ work in progressing through the first two steps in oral history outlined in The Oral History Manual; the idea and the plan.3 Of note, the “investigation” process of which I have so many times been a part in my professional career nearly exactly follows the five-step cycle, though of course the scope is vastly different and, I assume, my experience was filled with far more lawyers. Nevertheless, we find intensive study and research taking place long before the first interview. Perhaps the most (?) challenging aspect of the making of oral history is the planning of a project’s scope, and in identifying, if not a new target altogether, where the target hasn’t been hit. Then again, how can you really be sure where the target hasn’t been struck unless you can already see it up close?

At the surface, this appears to be an integral aspect of the nature of oral history—a healthy amount of flexibility between the intended outcome and the changes that inevitably occur throughout the span of a project. In this way, too, oral history and psychohistory are parallel. We will plan a project in great detail and the project will require significant revision, redirection, and maintenance before we see it through. However, I am confidently optimistic that we will not be supplanted by another (very secret) society.

- Donald A. Ritchie. 2015. Doing Oral History. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. https://research-ebsco-com.libproxy.temple.edu/linkprocessor/plink?id=8dadfb6a-aa65-3e1c-b634-6bbbf15bd69e. p. 11

- Barbara Sommer, Mary Quinlan. 2018. The Oral History Manual. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/templeuniv-ebooks/reader.action?docID=5423714&ppg=16&c=RVBVQg. p. 21.

- Ibid. pp. 15-17.