In 1977, Rob Rosenthal conducted interviews in Seattle, WA, while researching for his MA thesis. He studied the 1919 general strike in Seattle, interviewing the men and women who were present or had valuable knowledge of the 1919 strike. The interviews generally follow a typical layout of prescribed questions. Still, one interview stands out as remarkable, if not for its invaluable information regarding the interviewee’s experience during the 1919 strike (he may not have been there), then for the interviewee’s life experience in labor unions during the early 20th century and, more generally, the ability for oral history projects to unearth fascinating information even if the information found isn’t quite what was searched for.

George Hastings (a pseudonym) was, at the time of the 1977 interview, 87 years old and full of vigor, regaling Rob Rosenthall with his life story for nearly two and a half hours. Each interview includes a synopsis, likely from Rosenthal’s field notes. These synopses are more so word pictures than they are biographical in nature, and Hasting’s synopsis reads as follows:

“Age in 1919:29 — Occupation: Uncertain, probably lumber camps Not even clear if he was in Seattle during the Strike. But a Wobbly with a tremendous amount to say about all sorts of things tied to labor struggles of the day.”

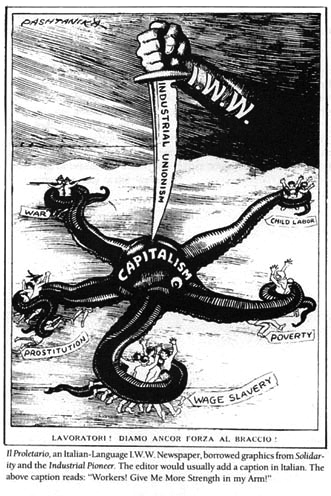

Rosenthal appears to take a different approach in this interview than in others, refraining from following his scripted questions with as much care to the structure of the interview, in this case allowing Hastings to, in the wide sense of the word, ramble on for a considerable duration before any attempt is made to focus on the 1919 strike or even labor in general. This leads us to some questions regarding the inclusion of this interview in the project. Acknowledging that Hastings may not have even been in Washington at the time of the Seattle General Strike and finding nowhere in the interview suggesting that Hastings was involved in organizing that strike, what does his story have to bear on the strike? In his interview with Virginia Redding, Rosenthal spends fifteen minutes asking questions before determining that Redding has nothing more to say regarding his project, and the interview ends. How then do we have two and a half hours of everything under the sun with Hastings? Perhaps Rosenthal felt the need to listen to an aged man waxing eloquent about his life, or perhaps he believed that there was vital information in Hastings’ story. I believe the latter. To put it succinctly, we get to listen to the lifecycle of one self-professed revolutionary. I use the term lifecycle here deliberately, with Hastings recounting his upbringing, education, how his views differed from classmates and teachers, his experience in the armed forces, his introduction to influential labor unions such as the IWW (the “wobblies”), advocating for free speech, being thrown in prison, and gradually becoming dissatisfied with the middling resolution of what he viewed as a labor revolution.

The logistics of the interview are limited by circumstance, with this one taking place in what is most likely a union retiree club or retirement home. A radio or television plays in the background, other voices are heard, and the microphone occasionally disappears, perhaps into the fold of a suit or the cushion of a couch. These minor details aside, it appears that Hastings had far more to say than Rosenthal was prepared to receive. This is no slight against Rosenthal; he went in for a discussion of the 1919 Seattle General Strike and got Hastings’ life story with sidebars ranging from manned gliders to the IWW organizing strikes in North Dakota. Taking seriously the ability of the expert interviewer to improve the subject’s memory and focus, it becomes apparent that a more fully prepared interviewer could have engaged in either greater breadth or greater depth (or both, if the interviewer had many, many hours to spare) than what Hastings was able to provide in his mostly stream-of-consciousness manner.

At the end of the interview, perhaps like Rob Rosenthal in 1977, I’d love to hear more of what Mr. Hastings has to say. In fact, I am sure that we both have some follow-up questions for him.

Interviews: Oral Histories – Seattle General Strike Project

As the George Hastings interview has no transcript, some (but certainly not all) of the interesting points are transcribed below. Timestamps are approximate.

12:15:

Hastings: I am far to the left, as they say, how can anyone with nothing left to lose, lose? I am receiving honors … for the things that I was condemned and oftentimes in prison for in years gone past…

Rosenthal: I hope you’ll tell me that story later.

Hastings: What?

Rosenthal: [somewhat louder] I hope you’ll tell me that story later.

Hastings: You know, times move… I am writing my editorial for July–I always try to tie it in with a time and I tied it in with July Fourth… [long pause] The first man who advocated that the colonies be independent of the British crown was a rebel… He was not well thought of in his community.

1:10:00

Hastings: The next step from tribe to clan to nation didn’t take one-twelfth the time from the family to the tribe from the building of cities to the forming of a nation with all the political structures and from city to kingdom from kingdom to empire, all of that has occurred within the last twelve thousand years. And to think! When we don’t know how many thousands of years man existed before the first city was built, before the first tribe was born! You can see how this is accelerating logarithmically rather than arithmetically or even geometrically.

Rosenthal: What sort of things did you do when you joined the social party?

1:18:00, after a discussion about some sort of glider, which Mr. Hastings helped to push, “with a tremendous ceiling of about 500 feet.”

Hastings: While I was there I heard about the free speech fight . . . which was started in Minot [North Dakota] now this developed around the fact that they were building, well there was, I think it must have been oats or something but the thing was they were building a normal school, teacher’s college we call it now, at Minot and the contractor taking advantage of the fact that there were hundreds and hundreds of harvesters waiting for the harvest and cut the wages down … I don’t know the actual wage paid, but perhaps something like a dollar fifty cents, a dollar twenty-five, a dollar fifty cents a day, something like that, just not even a subsistence wage… but the IWW came in there and they got the jobs done, they got the job and organized a strike, which didn’t suit the city one bit. They began to round up the IWW and drive them out of town… to break the strike.

2:18:00 Did you remain a wobbly all that time?

No, first of all I became dissatisfied… I was an organizer, an advocate if you please. As when things just were static and peaceable and nothing–no struggle to carry on or being carried on, then I began in ordinary intellectual abilities and so on there didn’t seem to be anything to do and I began to disapprove of some of the things I saw, and maybe I was wrong. But I could not be a member of the IWW as a simple labor union–as a labor union pure and simple. When the revolutionary concept was no longer practiced, then I no longer… because from the time I first come into contact with the social party and all through my subsequent experience I felt the necessity for change, and that man is a conscious contributor to that change. It’s by the knowing and realizing the forces which control society and the economic structure we have some… we have the knowledge of these forces, we have some chance to somewhat control them just as we use the wind to drive windmills and ships for sailing, you see. We use the force of gravity to distribute… So, in economic forces we can somewhat be in control of them. But the only–I want social change, I want that form of society in which the welfare of the whole is the paramount issue. I want–I hope to see–I hope the world, the people of the world are moving towards that place where inequity and injustice are not perpetrated. They may occur infrequently from unrighteous causes but were the… and that is going to take first, the realization that all the working groups, all of the people who are working for wages are under the control of any sort of American tax, have a common purpose, that they have common interests, that injury inflicted upon any one is a concern for all of us and that we must unite as one–nobody else can do it–it must come from this, the lower class [recording ends]