By: Macey Mento

Research Question: How do youth reentry programs combat or exacerbate the polluting nature of carceral geographies? How do government youth reentry programs differ from community-based ones?

What is youth reentry? Why does it matter?

Reentry refers to the process of an individual returning to the community after being released from prison. To assist with this transition, both government bodies and nonprofit organizations have formed programs designed to minimize the potential of recidivism. These programs can take the form of education and job pathways, healthcare, housing, therapy, and other social services.

Literature on reentry in the context of the juvenile justice system is limited. However, what information does exist emphasizes how understanding reentry at the youth level is important for framing our understanding of reentry as a whole. Additionally, by examining youth reentry programs as they are presently structured, we can see how such programs risk acting as an extension of the prison, enabling the existence of carceral spaces and pollutants. In contrast, we can also observe how programs integrate abolitionist goals and act as vehicles of restorative and transformative justice.

The Current Youth Reentry Landscape

Researchers have found that…

- Approximate number of youth released annually: 100,000-200,000 (Abrams, 2021)

- Majority are between 15-20 years old at the time of their incarceration and release (Abrams, 2021)

- Majority are male (Abrams, 2021)

- Majority are Black and Hispanic (Abrams, 2021)

- Majority come from single parent homes or “did not live with a parent prior to incarceration” (Abrams, 2021)

- 1 out of 11 youths were parents themselves at the time of release (Abrams, 2021)

- “Up to two thirds of released youth will be rearrested and between one quarter and one third will return to prison. This cycle of removal and return of large numbers of young people is increasingly concentrated in communities already experiencing enormous disadvantage” (Mears & Travis, 2004)

Government vs. Community-Based Youth Reentry Programs: A Discourse Analysis

The type of support adolescents receives upon being released from the juvenile justice system is not uniform. There is immense variability in the services, resources, and priorities of youth reentry, and the differences between government and community-based programs clearly highlights this. To understand these differences, I conduct a discourse analysis, observing how the language used around both types of programs symbolizes the larger issue of the state’s inevitable role in perpetuating carceral spaces.

Understanding Government Youth Reentry Programs

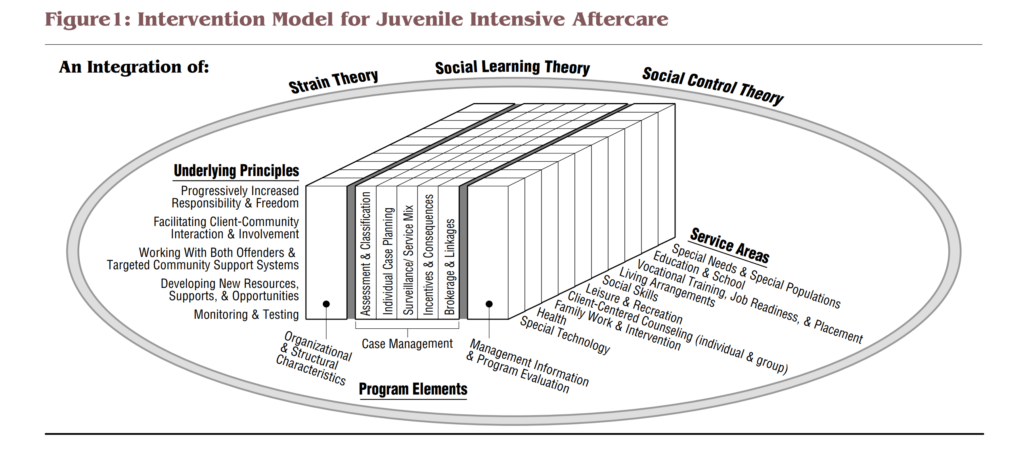

This report, published by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, has long been the model for how youth reentry programs should operate. While the “underlying principles” and “service areas” in Figure 1 above speak to the idea of individual needs, the guiding principles of reentry programs (bullet points above) convey a much different message. They frame reentry as something that must be individualized to succeed. Further, principles 3 and 4 demonstrate quite clearly how government reentry programs can act as extensions of the carceral system. “A mix of intensive surveillance and services” and “a balance of incentives and graduated consequences coupled with the imposition of realistic, enforceable parole conditions” (OJJPD, 1994) demonstrate how the focus of government youth reentry is not about the services themselves but on creating a controlled and surveilled environment for the released youth to navigate.

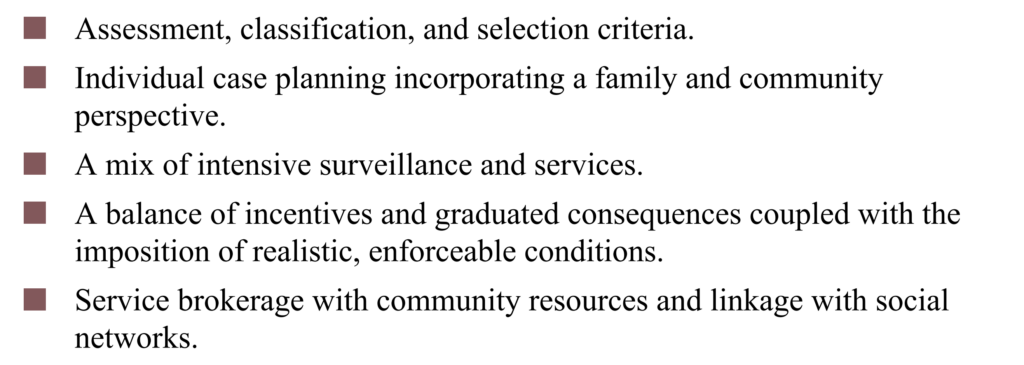

This survey administered by the federal Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention is demonstrative of what governments perceive to be important variables in the reentry process. The percentages themselves are far less interesting than the metrics used, particularly the first six statements. Not only are they quite slanted and leading in nature, but they speak to the hyper-individualized nature of the process, drawing attention to the character and goals of the juvenile rather than the services.

As stated by the U.S. Office of Justice Programs:

These [youth reentry] programs generally focus on changing youth’s individual behavior and help them develop practical skill sets to prevent further delinquency and ensure their successful reentry into the community.

United States Office of Justice Programs

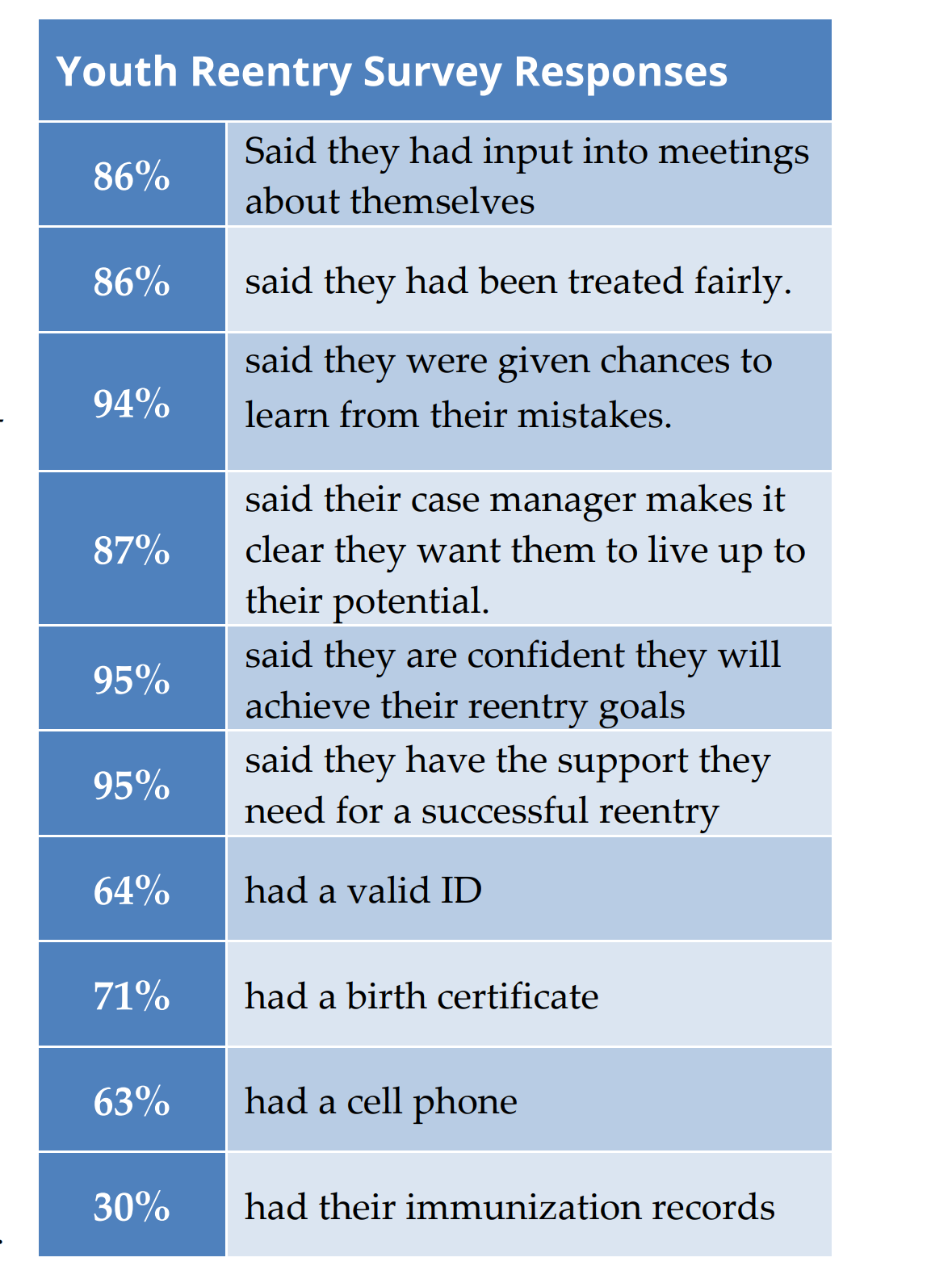

This table from Bondoc et al. (2021) highlights how the majority of parents and providers of released youth identify the “structural barriers to reentry” as the most difficult aspect of reentry to overcome. This involves not only medical insurance, as shown in the example, but access to school, therapy, and other resources. Despite these being the resources the government claims to create for youth upon release, they are still challenging to access due to constraints like money, time, and distance. Therefore, it is the system of reentry as it is set up by the federal and local governments that acts as a barrier to youth successfully and seamlessly transitioning back into their communities.

Bondoc et al. (2021). “Overlapping and intersecting challenges”: Parent and Provider perspectives on Youth Adversity During Community Reentry after Incarceration. Children and Youth Services Review, 125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106007

The Polluting Nature of Reentry Healthcare

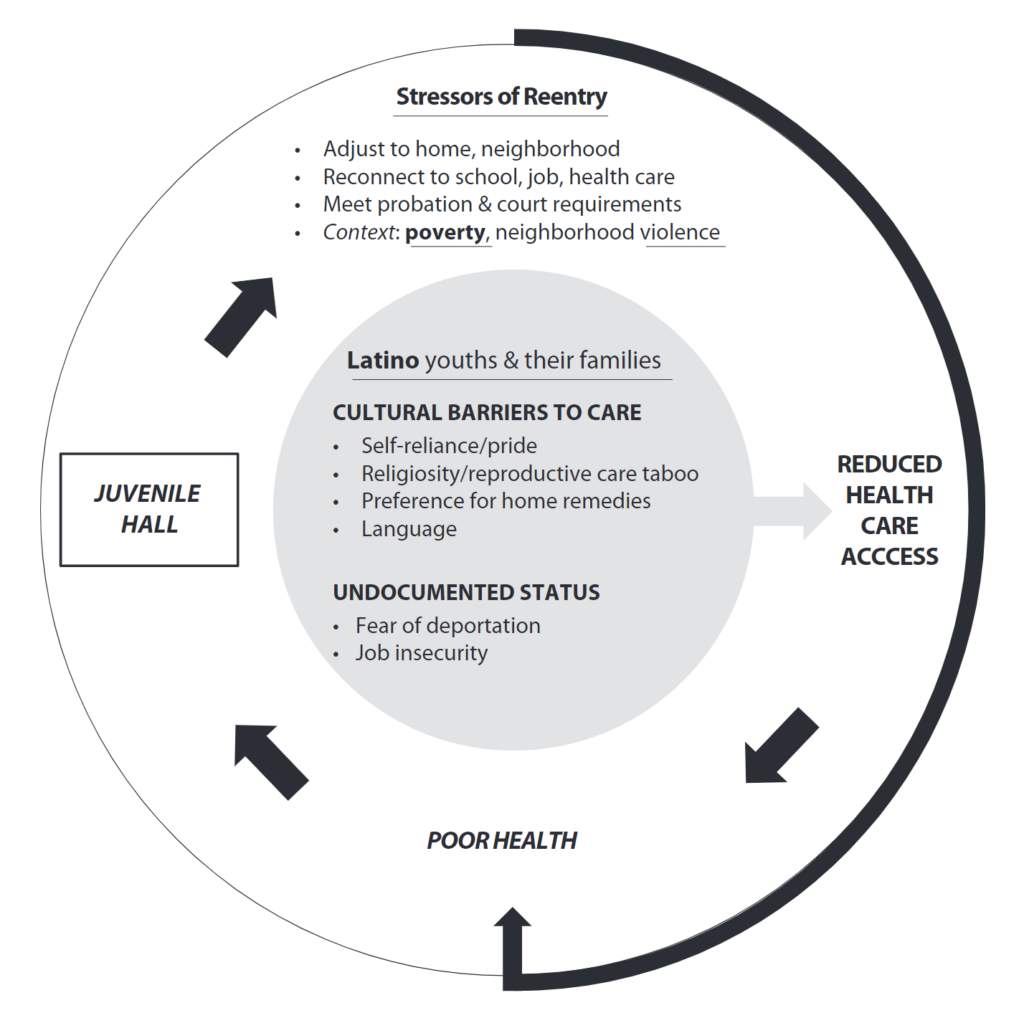

This figure from Barnert et al.’s 2020 research on Latino youths’ access to healthcare during reentry highlights how the juvenile justice system acts as a pollutant to that which is beyond it. The carceral threat of deportation, along with systemic issues like poverty, only worsen health care access for lower income, POC communities, which already have restricted access due to insurance barriers. Thus, the body becomes a site of possible pollution, as it cannot rely on consistent medical aid due to capitalist structures of the healthcare system which are perpetuated by carceral features (Barnert et al., 2020).

The Tribal Green Reentry Initiative

- Lundquist et al., 2014

- From 2009 to 2014

- Funded and organized by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention

- “Green Reentry” grants given to 3 Native American Tribes (Hualapai, Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, Rosebud Sioux)

- “Combined conventional juvenile justice programming–such as individual assessments, reentry planning, education, and counseling–with green activities such as gardening and skill development in green technologies”

- Involved youth returning daily to the green site to partake in the reentry and greening programs, some of which were at the carceral facilities

- Probation officers, law enforcement, and courts were all involved in adminstering programs and monitoring participation of youth

- A form of green justice initiative

In a 2013 study of the Powelton Aftercare reentry facility in Philadelphia, PA, scholars Jaime Fader and Christopher Dum found that even when government-backed youth reentry programs provide the social services they claim to, it is done so in a way that can be seen as "bureaucratic ritualism". By this, they mean that the rigid and processual nature of such programs (whether that be through immense paperwork, time limits and deadlines, or need for coordination between care services) was a major barrier to released youth actually receiving any assistance that they were promised. This devotion to the bureaucratic process, which is inevitable in the face of the state, only fails youth by creating additional barriers and constraints to receiving necessary aid (Fader & Dum, 2013).

“Community Washing”

Similar to the idea of green washing and community policing, "community washing" is a way to describe the phenomenon that scholars like E. Brown (2014) discuss. Governments engage in community washing rhetoric when it conversations and policies around youth reentry. They use the term community to paint youth reentry programs in a more appealing light, making it appear as though they are based on a neighborhood-focused model of empowerment. The use of the term in reports and program guides, creates the illusion that communities possess some agency over the youth reentry process. However, "the community orientation [of government programs]...extends the power of the state over a broad geography that results in the coerced mobility of children and subjection to greater insecurity...the carceral apparatus extends into neighborhoods" (Brown, 2014).

Findings: Government reentry programs hyper-individualize the reentry process. By doing so, they overlook the systems that disadvantage a neighborhood in the first place, perpetuating carceral spaces and pollutants. These types of programs are also reactive, providing necessary services on the backside of incarceration rather than the front side.

Community-Based Youth Reentry Programs

“From the standpoint of neighborhood effects theory…change is likely required on many interacting levels of the youth offender’s familial, social, and ecological landscape…what we envision is an approach in which neighborhood and individual factors are addressed in an integrated, rather than mutually exclusive fashion.”

Abrams, L. (2021)

To understand the value and benefit of community-based youth reentry programs, we can turn to a real-world example…

YSRP, one of the most established and successful community-based youth reentry providers in the country, is located in Philadelphia, PA. Similar to government reentry services, YSRP does create individualized programs to help released youth and their families. However, the focus is: how can the community help the individual? As opposed to the governmental approach of: how can the individual re-fit back into society?

How YSRP does this:

Hiring of and partnership with formerly incarcerated youth

In YSRP’s 2017-2018 report, the organization highlighted their “reach back” philosophy. This entails hiring formerly incarcerated youth into positions of leadership at YSRP, as well as partnering with them to organize workshops and reentry prep mentorship.

Pennsylvania JLWOP Reentry Navigator

This free tool on the YSRP website connects recently released youth and their families to a network of social services resources across Pennsylvania. It is a highly accessible, completely anonymous search tool and creates a sense of authority and agency for an individual, allowing them to see what is out there available to them before being tied into a program.

Intergenerational Healing Circle

As described by the YSRP, the IHC “centers healing from trauma and builds power among young Black men and former juvenile lifers who share the experience of being prosecuted as teenagers in the adult justice system” (YSRP). The IHC functions very similar to the community circle concept seen in abolition studies, creating a consistent space of dialogue for a large number of people. The four core goals of the IHC are: 1) understanding and healing from trauma, 2) creating connectedness rooted in shared experiences of incarceration and reentry, 3) developing agency and liberation-oriented leadership, 4) building collective power. This model, which has been in place at YSRP for the past four years, speaks to the restorative justice concept of focusing the attention on the survivor (in this case, the formerly incarcerated youth) rather than on the perpetrator (the carceral system).

Youth Advocacy Project at UPenn

About a decade ago, YSRP started the YAP program with Penn Law School. It allows student volunteers from the law and social work departments to provide research and resource support to youth and families involved in the juvenile justice system. Volunteers do “leg work” for the clients, such as documentation, applications, referrals, researching. They also engage in community education on mitigation. This program rejects the hyper-individualized nature of government reentry programs that put a lot of the responsibility on the youth, their families, and the system-entrenched parole officers/social workers. It emphasizes the need for community effort when it comes to breaking the cycles of incarceration and also does front-end, transformative justice type of work. Additionally, it bridges the massive gap between college students and Philadelphia youth, another important transformative justice element.

Other real-world examples of community-based youth reentry and transformative justice programming:

Finding: Community-based youth reentry programs shift the focus from the individual’s reentering into the community to the community’s ability to help that individual reenter.

Programs like YSRP are an essential step in the direction towards moving beyond a carceral world. They work to create a community around the reentering youth rather than rely on bureaucratic, out-of-touch ways to “reintegrate” the individual into society. This approach leans more in the direction of restorative justice. However, if the goal is to live in a world free from incarceration, services cannot stop there. A more transformative justice framework must be applied. Services like the Intergenerational Healing Circle and Youth Advocacy Project must exist in front of incarceration, not on the back side of it. A truly abolitionist world shaped by transformative justice would not even involve the idea of “reentry”. This is something that only community-based organizations can work towards, and we see this beginning with organizations like YSRP.