By: Sophia Mosley

Research Question: How have juvenile incarceration facilities, specifically, the JJSC in Philadelphia, enhanced the social and environmental pollution seen in the area of its operation, and individuals who are kept there?

Juvenile justice throughout out country is an institution which is painted largely as a strong source of rehabilitative care. To some it is seen as a proper punishment to crimes, and for others it is seen as a way for youth to rehabilitate their poor behavior. Either view of youth incarceration still paints the same picture, it has become engrained in our country as a piece of youth behavioral management. Often these facilities lack adequate staffing, resources, funding, etc. making them yet another form of legal abuse and punishment for our youth, especially our youth of color.

Overview: The True Reality of Youth Incarceration

The true nature of youth incarceration is inherently oppressive, and traumatizing to the children who are forced to serve time in these facilities. They are often arrested, and held in these facilities for many months before they even have the opportunity for a trial. As young as 13, a child can be held in these facilities for most of their formative years. As a result of their incarceration, the child’s development is severely hindered. Highlighted in a study conducted by the Journal for Development and Psychopathology, impulse control and maturity levels are developed over the course of adolescence; however, the increasingly violent and hostile nature which is prevalent in youth incarceration facilities drastically affects the development of the children serving time there. Thus, the youth who spend time have a higher conceivability for suppressed self regulation and impulse control. This study introduces just one of the realities of youth incarceration, its increasingly failing conditions, and the lasting effects it has on our youth who need help.

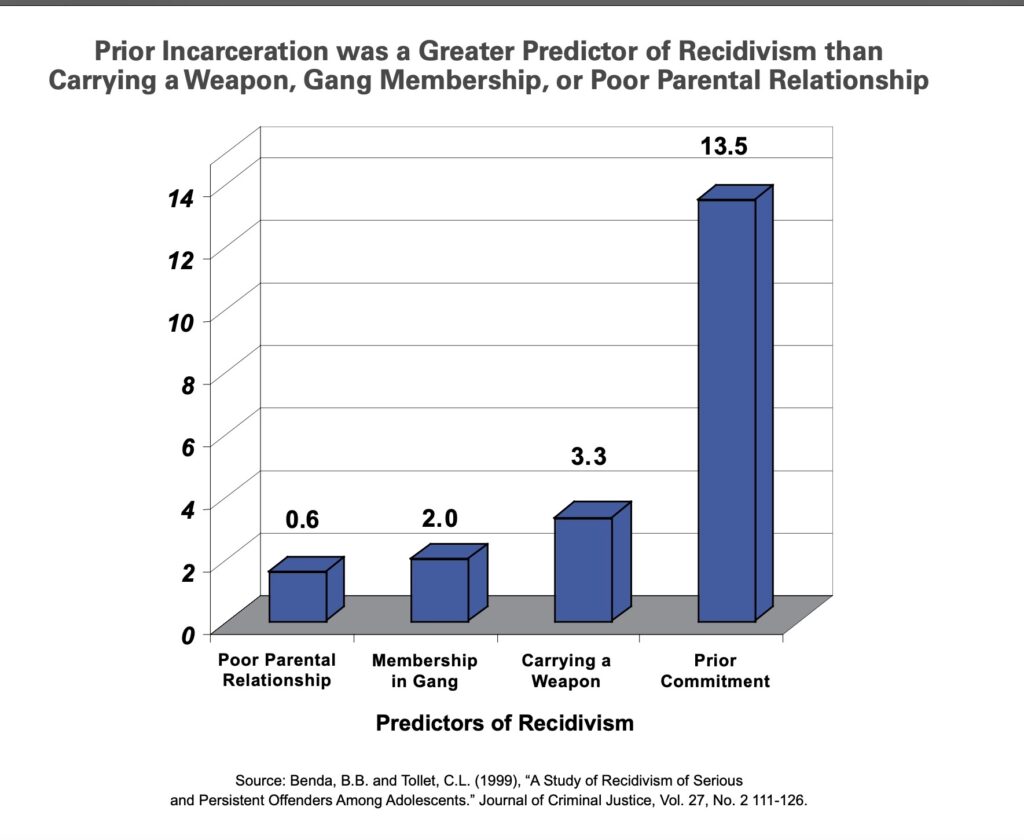

The Juvenile Law center also paints a clear picture of what youth incarceration is doing to children, as opposed to for children. They state, ” Children may be locked in cells as small as seven-by-ten feet, 22 to 24 hours per day, with no personal belongings, no access to educational services, counseling or mental health treatment, no interaction with peers and with nothing more than a lightly padded concrete slab to sleep on” (Juvenile Law Center 2024). This is the reality of youth incarceration, abusive and traumatic for youth who already need extra help and support from our system. The Justice Policy Institute further outline this reality, and what it means for the future of our disadvantaged youth. By pulling youth offenders into the carceral system at such a young age, youth incarceration increases both reffoffense and recidivism rates. Shown below is a figure which outlines the disproportionate effects which youth incarceration has on recidivism rates.

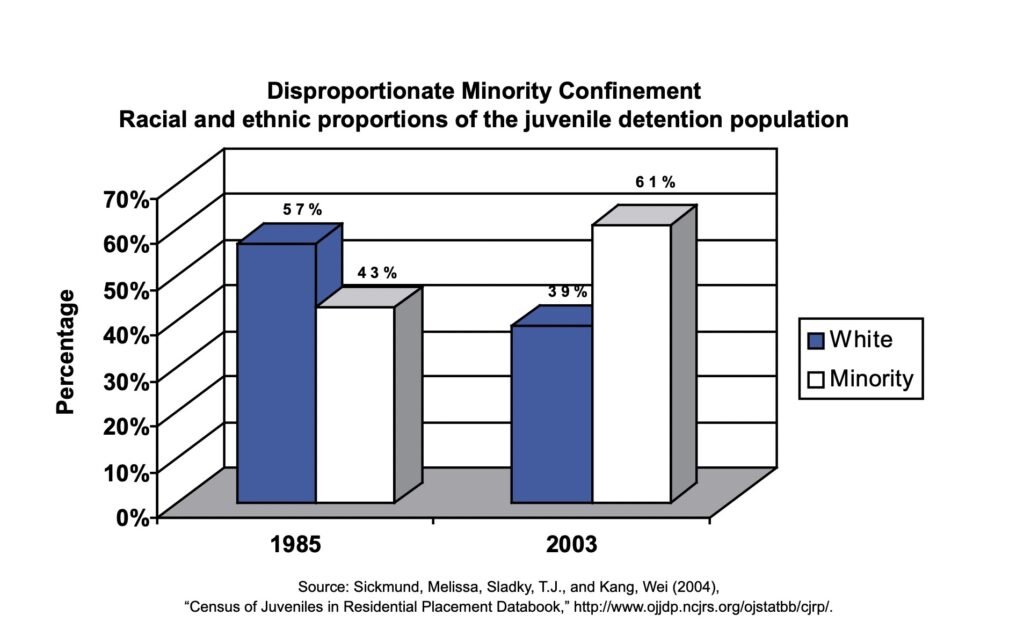

The aforementioned conditions are not just unfortunate by products of juvenile incarceration either. They are in reality core foundations which this institution operates. Another aspect being the disproportionate effect in which youth incarceration has on black and brown youth from low socioeconomic standings.

“A distinguishing characteristic of the correctional confinement population is the overrepresentation of minority youth. In 1999, two-thirds of all youth in public facilities and more than half of youth in private facilities (55 percent) were minorities”( Rodriguez 2023)

“racial disparities at intake outcomes were attributed to the financial status of White middle-class families who were able to provide private services (e.g., counseling, substance abuse treatment) and thus prevent further system penetration of youth. For many minority youth from lower-class families, the only way to receive services and treatment is through adjudication and confinement . In the end, disadvantage matters in juvenile court outcomes because youth lack adequate resources to thrive in their communities”(Rodriguez 2013)

Concentrated Disadvantage and the Incarceration of Youth: Examining How Context Affects Juvenile Justice, Sage Journals.

Not only are the conditions of juvenile incarceration facilities inherently abusive and traumatizing , but the disproportionatley victimize our black and brown youth. It is important to understand these implications, as we begin to explore the social and environmental pollution, specifically in the city of Philadelphia.

Social and Emotional Pollution Within Juvenile Justice Facilities

Often our view of pollution is crowded by our one sided view on what a “pollutant” looks like. We often think of physical, tangible forms of pollutants as opposed to recognizing that pollutions can in fact exist in all forms. The juvenile justice system has created an environment where social/emotional and physical pollutants are just a routine part of these institutions. Certain United States protocols and regulations have seen youth offenders being matriculated in with adult offenders, reducing their access to true rehabilitative care. Despite the fact that according to the UNCRC (United Nations Convention on the Rights of Children), children “In particular, every child deprived of liberty shall be separated from adults unless it is considered in the child’s best interests not to do so” (Lambie 2013). The social and emotional effects which being tried as an adult, or serving time with adult offenders may have on a child is unprecedented. Not only must they persevere through the trauma of the carceral system, but they most do so as a child who is struggling to mature and grow every day.

There is no current standard for the quality or system of mental health care within juvenile corrections, yet research has shown “that for one-third of individuals that are diagnosed with depression while incarcerated the onset of the disorder occurred during incarceration”( Roberts, 2013). Without any minimum acceptable standard of mental health resources, incarcerated youth will continue to suffer. There is also no universal way in which this system helps those incarcerated through their trauma of being removed from their home and jailed. From the point of arrest to being held, it is an increasingly traumatic experience yet this is often ignored when thinking of the by products of incarceration. Over the course of my research, I found works published by the Youth Law Center which states “We also know that the effects of trauma do not end with arrest. Trauma continues to affect behavior in day-to-day interactions, as youth respond to painful experiences and loss, exhibited in depression, fear, and anxiety; low self-esteem; self-destructive behavior; combative self-preservation; mistrust of adults; perceptions of unfairness; uncontrolled anger; deep sadness; and extreme sensitivity to rejection” (Burell, 2013).This form of pollution while not tangible, is just as dangerous to the future of society and our children. This form of societal pollution only ensures that our youth who were born into struggle, will only continue to struggle within a carceral system.

“Upon entering the detention center, Karik saw a psychiatrist for an evaluation. They discovered his anger problems, and some environmental factors that led to this diagnosis. Unfortunately this was the last Karik ever saw of the psychiatrist. Other individuals needed immediate psychiatric attention and constant supervision. Karik fell to the back burner and did not receive the psychiatric support necessary for recovery.”

Meredith Roberts The Ethical Implications of Juvenile Detention centers and The Role of Mental health and Education in Reducing Recidivism. Washington Lee University

Juvenile detention centers also fail to adequately address physical health pollution as well. Not only do incarcerated youth struggle to obtain social and emotional support, their physical health is severely neglected. Incarcerated youth are at higher risk for co-occuring health risk behaviors, as well as disproportionate shared of adolescent morbidity and mortality(Golzari 2006). Over the course of my research, I was able to review a study conducted by Ian Silver at the Center for Legal Systems research in which 8.951 youths were studied in order to determine if mortality rates were higher among those who had been incarcerated before the age of 18. The results showed that “being arrested before the age of 18 years was associated with an increased risk of earlier mortality between 18 and 39 years of age when compared with individuals who were never arrested or incarcerated before the age of 18 years”(Silver, 2023).

This condition works in tandem with the harsh reality that health care access is limited, which heightens the health issues which come from basic lack of health care maintenance. “A national survey of youth in custody in 2003 found that two-thirds of the young people had one or more physical health care needs, including dental, vision, or hearing issues (37%); an acute illness (28%); or injury (25%)”(Barnet, 2016). The conditions in which young incarcerated individuals are subjected not only reduces their physical and social/emotional health, it neglects it as well.

Green Space and Environmental Pollution

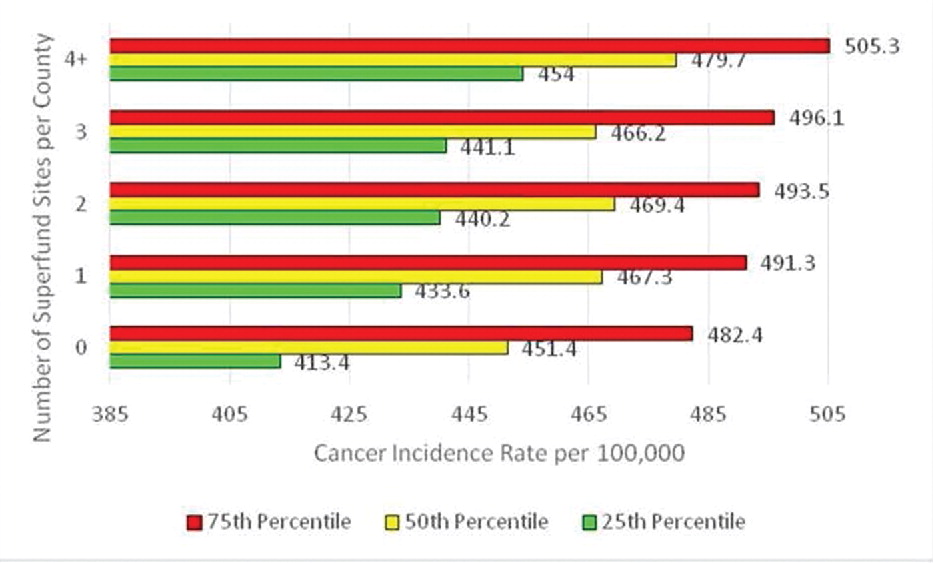

Many aspects of the youth incarceration system concern the pollution of our society. Whether it is in the form of social/emotional trauma, or physical health decline these systems are not protecting our children right down to the land in which they are built upon. Often times youth incarceration sites are built on open plots of land in which government organizations can obtain cheaply, and can begin construction as soon as possible. As a result the construction of juvenile incarceration facilities on superfund and toxic waste sites is an unfortunately sad reality. A geographic study conducted using ArcGIS published in the Journal of Environmental Justice concluded that:

“it was determined that, out of 167 sites housing juveniles, four are within one mile of at least one Superfund site, and 49 are within 5 miles of at least one Superfund site. In addition, examination of the health consequences of proximity to certain toxics suggests that there are legitimate dangers associated with being housed in a juvenile detention facility located near a Superfund site”

Harrison Ashby (2020), Superfund Sites and Juvenile Detention: Proximity Analysis in the Western United States

Every aspect of youth incarceration is interconnected in a series of ways which disproportionately put children at risk. Right down to the physical space in which they they occupy, the children who are serving time here are continually mismanaged and treated as though their livelihood is disposable. The physical pollution which results from these incarceration facilities being built on superfund sites, connects right back to lack of physical care for their health. In a spacial study published by the Journal of of Statistic and Public Policy, outlined a clear connection between increased risk of cancer and proximity to superfund sites (Amin, 2017). In the figure below, they highlight the clear connection between proximity to sites, and the associated high risk of cancer.

Throughout the semester we highlighted architectural and structure institutions which employ abolition ecology, versus green justice strategies. Often reforms and structural changes are highlighted as “green” and “sustainable” as they merely just aim to appear that way on the outside. Throughout my research thus far, I was able to see a myriad of examples in which Philadelphia’s JJSC (Juvenile Justice Services Center) uses green justice strategies to ensure the continuation of a carceral system. Norix furniture is a company which did work for the JJSC when it underwent a large rebranding in 2012. The goal of the project is as follows, stated by Department of Homeland Security Commissioner at the time Anne Marie Ambrose:

“The goal of the Center is to help young people who are involved in the juvenile justice system make better decisions and improve the trajectory of their lives,” said DHS Commissioner Anne Marie Ambrose. “This new facility embodies our belief that given the right support, children have an immense capacity for change.”

Anne Marie Ambrose, 2012 Philadelphia Tribune.

Outlined in a comprehensive case study by Norix Furniture, detailed their commitment to furnishing a facility which promotes an environment committed to learning and healing. They highlight a “bright and cheerful” environment, and wanted a space which feels “non confining” and conducive to learning for our city’s youth. However, given what we know about green justice and the deeply rooted nature of our carceral system, no configuration of furniture can reduce the damaging effects of the existence of the JJSC. This new rebrand cost the city of Philadelphia $110 million dollars, in the same year which the city was forced to close over 30 public schools. However, city officials highlighted this facility’s dedication to the proper education and support of youth, in order to help support local communities. The images below depict Norix Furniture design plans:

When evaluating this space on a surface level, we see that while ultimately lacking any true abolition ecology solutions, it also fails in many senses to meet any green justice initiatives. All of these spaces lack windows, and natural lighting, and truly only reflect a small sense of color. This is the design plan which according to Norix Furniture:

“This education-oriented juvenile facility focuses on providing spaces where youth counselors are given the technology and environment to utilize their skills in working with youth to encourage positive behaviors”

Norix Furniture Case Study, 2012

The Reality of Philadelphia’s Juvenile Justice Services Center

The true nature of Philadelphia’s JJSC has failed to meet any of its objectives after its 2012 remodel. Despite the millions of dollars poured into this institution, it is currently failing to even adequately house our city’s youth, let alone invest quality care into them. According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, as of September of 2023, the facility was holding 246 kids, 75 of whom were waiting state placement. Being held in this facility does not count towards these children’s sentence either, meaning they are often held in the JJSC for months before they are sent to another incarceration facility.

“The facility became so overcrowded and understaffed that kids have been sleeping on mattresses on the floors of the center’s admissions office and gymnasium. More young people were getting into fights and building makeshift weapons to protect themselves. In the fall, a large altercation broke out, leaving one juvenile severely injured and dozens of staff hurt”

” Kids were often forced to stay in their units — some of which are windowless — all day, sometimes with no schooling, according to two groups supporting young people inside”

Ellie Rushing, 2023 Philadelphia Inquirer

This million dollar facility is merely acting as a cell, and holding unit for hundreds of children. Failing to provide or even attempt to commit to any of the services which they claimed to be investing in during their 2012 remodel. Children are forced into a windowless, concrete box all day if they are lucky as some children are forced to sleep in offices, gyms, etc. The images below depict the current reality of the JJSC for our city’s youth:

As seen from the images above, children are forced to sleep on the floor in what looks like sleeping bags. The time in which. these children are forced to spend her can range from days to many months, as the system is so understaffed even children eligible for placement are being neglected. These images show a clear failure in both Norix architecture programs, as well as the city of Philadelphia to provide adequate support and resources for our youth. In fact, a city audit report from December of 2015, stated that the facility not only met, but even exceed expectations in regards to their facilities and systems in place. (United States Department of Justice, 2015).

It is important to note that this report was published in 2017, so there is gap of information between an updated audit of the facilities current conditions. However, this information noted that the facility had 3 areas which need corrective measures. These ares were monitoring and supervision, education, and risk based housing decisions. According to the report, the medical and mental heath services provided were exceeded, with the following explanation being given: ” All residents receive a physical within 72 hours of admission. All residents who have disclosed prior sexual abuse see a Master’s level therapist for an assessment within 14 hours if not sooner. Any transgender or intersex resident is also offered medical services through the Mazzoni Center, an LGBTI agency”( City of Philadelphia, 2017). None of this explanation includes consistent and continual access to health care measures throughout their time in the facility, nor continuing to monitor youth who may need extra care.

Where Does the Future of Youth Incarceration Go From Here?

A large part of our class time has detailed what the future of our carceral system would look like using true abolitionist ecology. Given my aforementioned findings regarding the conditions of Philadelphia’s JJSC, it is important to look at some possible alternatives and solutions to youth incarceration. Abolitionist framework recognizes that youth incarceration not only perpetuates a cyclical cycle of racism and violence, but it is also a largely ineffective form of behavioral management for troubled youth.

“In Ohio, a 2013 study found that the likelihood of reincarceration for a new crime increased steadily the longer young people remained incarcerated for an initial offense. Whereas 34% of youth who were incarcerated for one month or less were later reincarcerated, that share climbed to 61% for youth for who were incarcerated for 60 months”

Lovins, B. K. (2013). Putting wayward kids behind bars: The impact of length of stay in a custodial setting on recidivism.

We must push ourselves to realize that our current methods of youth behavioral and criminal management is not only ineffective, but a pollutant within our society. Durell M. Washington, from the University of Chicago outlines the need for abolitionist reform amongst incarceration. The first step he outlines, is the “moratorium of building cages”(Washington, 2021). From the ver beginning of this country, locking people up and chaining them to a cages was used to facilitate white supremacy and oppression. This practice being used today as a form of behavioral management especially for largely black and brown youth continues years of systemic violence.

He also highlights the need for both decarceration and excarceration where society can move beyond the continual facilitation of the Prison Industrial Complex, and instead focus on true rehabilitation and healing. He highlights the effectiveness of family based treatment programs, “The results indicated that youth who participated in the PLL (Parenting with Love and Limits) program were less likely to be convicted of a felony crime or be placed in a residential juvenile facility—at statistically significant levels—and also less likely overall to be re-adjudicated compared to youth under institutional care” (Washington 2021). It is institutions like these that will ideally help our society break our habits of carceral facilitation, and move into a future where we can truly support our black and brown youth.