This week’s readings all dealt with symbolism, emotions, and exhibits. The first article I read was “A Stage Set for Assimilation” by Christopher Green. This article addressed the model Indian school at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. The theme of the fair was four centuries of progress, which seemed like a perfect opportunity for the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) to show off their methods of assimilating Native Americans for the sake of progressing civilization. The article explores the complex planning process that went into creating a model Indian school for fair-goers to interact with. Green discusses how the BIA chose the model’s architectural plans, interior decor, materials to be displayed, and what would serve as the representation of children. It was interesting reading about the technical problems the planners faced, such as having to cut corners in the actual construction of the building to save money and how no one wanted to staff the building during the fair. Green also notes how many fair-goers did not bother visiting the model Indian school because it was isolated in the corner of the fairgrounds. Those that did visit the school, often didn’t interact with the exhibit the way the planners had imagined, oftentimes visiting sections of the school that were supposed to be off limits or not for display. There were also debates over whether Native children should perform in bands for spectators, and if so, how they should dress. Overall, the Indian school exhibit at the World’s Fair was created with a specific purpose, to show off how these industrial style schools could solve the nation’s “Indian problem” by transforming “savage” Indian children into assimilated and modernized students. However, the exhibit itself did not live up to the expectations of the planners. When faced with financial strains, the exhibit took on more of an anthropological approach in which Native children were encouraged to produce Indigenous style artwork and clothing in order to gain more attention from visitors. Ironically enough, the exhibit space that was intended to suppress Indigenous identity became a place for unsanctioned resistance through a creative reclamation of Indian identity. Though this is a historical example of exhibit planning, this article helped me understand how one-sided and often traumatic histories can be reclaimed and used as an opportunity to restore and display agency. This is applicable for museum exhibitors and interpreters today who have to work with the history of American colonization. Instead of telling the history of the United States as one of conquest and instead of showcasing Native Americans as objects of anthropological curiosity, material culture can be used to demonstrate agency through history and tell a story of cultural continuity and resilience.

Another article I read this week was Mariia Sturken’s, “Citizens and Survivors.” This article outlines the process of memorialization for the victims and survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing of 1995. The article begins by discussing how objects left on the fence of the bombing site, such as teddy bears were placed because people view them as objects of comfort. These bears left at the site, were eventually cleaned and sent to children across the world who were experiencing tragedy with the hope that these bears would serve as a symbol of comfort and reassurance. The article also highlights how the photograph of the firefighter holding the lifeless body of a child became a popular cultural icon of the event, which was a traumatic experience for the family of the child. When it came time to creating a memorial for the site, it was made clear that the memorial would have to be abstract and not be representative of any individuals, living or dead. Sturken describes the process of memorialization in Oklahoma and reveals a number of questions that arose from this process. Who should the memorial memorialize? Should the memorial address the needs of survivors? Should the naming of victims be incorporated? What to do with unidentified victims? The memorial agreed upon by the community were empty chairs with the names of the victims inscribed on an illuminated base. The chairs stand at different heights, reminding us that death does not discriminate. Most importantly, I think this article revealed how complex symbolism can be and how much of an emotional impact objects can have on people who lived through tragedy.

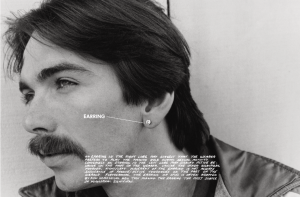

In a third article I read, symbolism is further discussed through a photo-text project by Hal Fischer called Gay Semiotics. This article discusses the cultural code of homosexual men in San Francisco in the 1970s. The study reveals how gay men have transformed physical objects into cultural signifiers, serving as a form of unspoken language. These objects were often earrings, bandanas, handkercheifs, keys, etc. These fashion accessories often symbolized the wearer’s sexual preference. The author notes that while these items were highly symbolic among the gay community, many other individuals wore them without the intention of implying the same meaning. This goes to show how seemingly ordinary object can have very different interpretations and can invoke response or nonresponse, which is also important for public history professionals to consider when exhibiting any object.