Lynn Abrams’s Oral History Theory introduces the notion that theoretical advances in oral history result from its practice. To think more deeply about oral history, one must combine all the aspects of its practice: interpretation, signification, and the interview process (Abrams 1). Abrams frames oral history as a distinctive field, one whose differences must be explored in contrast to other types of histories. Borrowing from Portelli, she names some of these differentiating aspects to be: orality, narrative, subjectivity, credibility, objectivity, and authorship (Abrams 19). As she proceeds throughout the book to discuss the unique complexities of oral history, one particular thread stood out to me.

I appreciate how she continuously incorporated explanations of how gender might play a role in interviews. This felt particularly relevant after touching on the same subject while reading Swing Shift, and having similar issues arise during my own interview last week. (Seeing how gender-based issues had already made themselves known, I can understand Abrams’s previous point about theory becoming relevant through practice). Abrams discusses various ways that feminist research methods have recognized the way in which gender affects oral history interviews: women’s voices being affected by the patriarchy rather than reflecting their experiences, women being uncertain as to how to narrate their lives because they were unfamiliar with public speaking, and women’s voices being more hesitantly expressed when their stories did not align with gendered expectations (71-72). Additionally, she writes that women’s storytelling often takes a different form than men’s storytelling in a group setting. Some of the differences that she notes includes: “women are more likely to support one another, interrupt in a supportive way, and adopt politeness strategies in order that all members of the group may share in the telling” (Abrams 119). I enjoyed her defining of women’s storytelling as a social production, and of women as doing “narrative labor” within the family (Abrams 119).

This concept of narrative labor frequently arose during class, and within my own life/interview. In class discussions, we made references to ‘grandmas/aunts/mothers’ that knew family history or favorite stories — a sentiment which I shared in my own life, as many of my older aunts know much more about my family history than I do. I’m curious as to how that expectation of narrative or emotional labor might show up within a museum or institutional interview, and how it might be avoided. Regardless, these discussions of feminist oral history in Oral History Theory made me think about all of the various women in museums that I’ve met who are often more engaged in networking across institutions and establishing relationships with volunteers, and then bring that knowledge back to their home institutions.

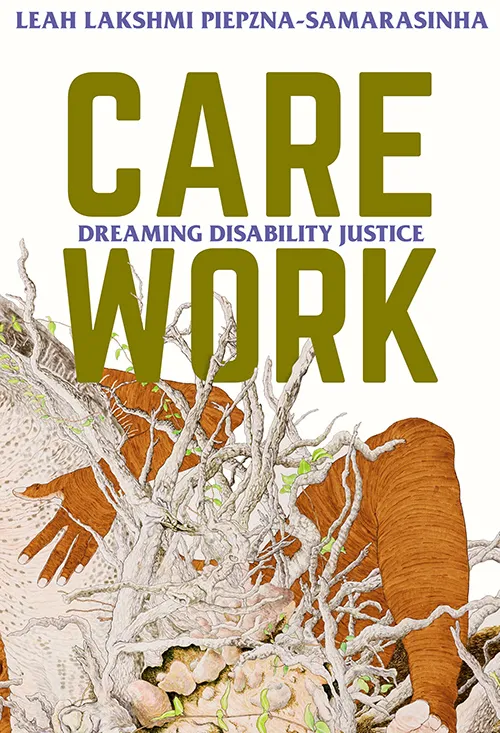

After reading this book, I was trying to think of another work that acknowledges women’s emotional labor well, especially women that are disabled and/or people of color. I got into reading disability theory and history books over the summer, and one of them that I enjoyed was Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha. Piepzna-Samarasinha includes various anecdotes from disabled people … my memory is failing me if they did any formal oral history interviews … but I think so. I do remember an interesting section about queer femme emotional labor within disabled communities, that was a very effective exploration of how the ‘disabled’ social minority label did not let queer femmes escape the expectation of their other social minority identity as women. (The expectation here was often of women as connectors and organizers of groups of people). Moving forward, I’m going to be thinking about how these sorts of expectations might show up within an institution or within an interview!

References

Abrams, Lynn. Oral History Theory. London and New York: Routledge, 2010.

Piepzna-Samarasinha, Leah Lakshmi. Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018.

Be First to Comment