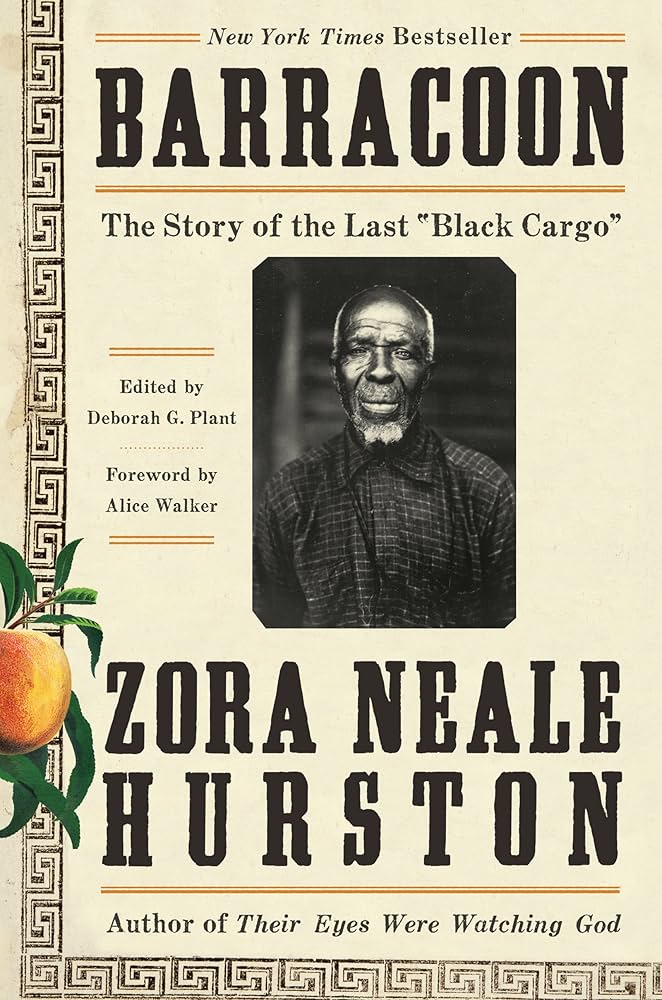

Why have spoken history and oral tradition struggled to maintain credibility? This question remained with me through Ritchie’s article, “An Oral History of Our Time,” and through the “Introduction to Oral History” from the Oral History Manual. Having earned an undergraduate degree in anthropology, I have spent some time exploring how interviews cemented themselves into anthropological practice. While anthropologists quickly utilized the interview as part of their discipline, historians initially shied away from the practice.1 Despite this difference in their respective timelines of accepting the interview as a practice, anthropology and history share common ground in that the interview was not often viewed as credible. For example, Ritchie notes that “many historians dismissed these interviews with ‘aged survivors’ [former enslaved people] as less reliable than the records kept by slave owners.”2 This instance reminded me of the celebration surrounding anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston’s work, Barracoon, in which she interviews Oluale Kossola, who was a prisoner on the final slave ship to the US. The work was based on her 1927 interviews with Kossola, but was never published until a century later (2018) due to a lack of interest from the publishing industry.3 It is fascinating to me how long oral history has been pushed under the rug, or viewed as less credible than written sources — likely tied to some heavy discrediting on the part of Western historians/anthropologists when encountering other cultures with different forms of record-keeping.

But just as oral history was once used to discredit certain groups, it is now a tool for uplifting the disenfranchised. It allows those lacking a written record to establish a place in history; it can even be used for larger groups, such as through community-based interviews.4 Even more encouraging is that the process itself is an accessible one, both articles this week emphasize the importance of making oral history accessible and preserving it for generations to come. Oral history is not only an accessible product, but an accessible practice, in which a ‘layperson’ could be trained.5 (Hopefully that proves to be true this semester, as I bolster my own oral history skills).

Having spent time in more traditional archival institutions, such as the Philadelphia Trio of the American Philosophical Society, the Library Company of Philadelphia, and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, I’m curious as to where these oral history recordings are preserved in order to ensure access. Is it preferred to have digital copies for more widespread access, or physical ones to ensure preservation within an institution? Moving forward, I’m interested in how this preservation aspect will be carried out in our oral history projects this semester; how will we decide to best preserve them? The last two steps in the Oral History Life Cycle (Idea, Plan, Interview, Preservation, Access/Use),6 seem like they will be the most complex to figure out in relation to our projects this semester. In a few months, it will be useful to see how that life cycle varies project by project, or institution by institution. Looking through everyone’s oral history dossiers encouraged me to start getting excited about the variety of avenues to pursue in the coming days …!

ES

- Ritchie, Donald A. “An Oral History of Our Time,” in Doing Oral History: A Practical Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003, p. 3.

- Ritchie, 4.

- Rothman, Lily. “Zora Neale Hurston’s Long-Unpublished Barracoon Finds Its Place After Decades of Delay.” Time Magazine. 10 May 2018. https://time.com/5272335/zora-neale-hurston-barracoon-published/.

- Sommer, Barbara W. and Mary Kay Quinlan. “An Introduction to Oral History,” in The Oral History Manual. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2018, p.11.

- Sommer and Quinlan 3; Ritchie, 9.

- Sommer and Quinlan 5.

Be First to Comment