The Coronavirus pandemic is a global phenomenon unlike any other, at least in terms of speed (more than climate change) and reach (more than trade). Its effects and consequences in different countries and societies are remarkably diverse. The College of Liberal Arts at Temple University is fortunate to have among its faculty many area specialists, with deep knowledge about a large array of countries. The Global Studies Program has created this new public platform to share some of this knowledge. Our goal is to collect short essays on the Coronavirus experience from around the world. These are not the big picture articles that tend to dominate in the US media (such as “the future of globalization” or “what will happen to international trade”); rather, we wish to highlight stories or ideas or conditions that are specific to places or countries. This is a living document. Please consider sending your own essay to enrich the breadth of our collective knowledge, to globalstudies@temple.edu.

The Essays:

- The Caribbean by Harvey Neptune

- Congo and Haiti by Terry Rey

- Germany by Richard Deeg

- India by Sanjoy Chakravorty

- Myanmar (Burma) by Jacob Shell

- Palestine by Alexa Firat

- Peru by Mónica Ricketts

The Caribbean: Quarantine Culture

Harvey Neptune, Associate Professor, Department of History

Mobility has been a defining feature of modern Caribbean history. Especially since the end of slavery and indentureship by the early 20th century, the will and wherewithal to travel across and out of the region has been a precious human resource. Caribbean people move. In fact, for many born in the region, leaving their place of birth has been the key to making a life and earning a living. The arrival of the corona virus has put a dramatic pause to this enduringly moving way of being. Though some states re-opened their borders months ago (largely due to economic dependency on tourism), much of the Caribbean has been under virtual “lockdown” for the past eight months. This has been true for the twin island republic of Trinidad and Tobago, whose government has taken a strict and relatively effective approach to dealing with the deadly virus, restricting, among other things, commercial air traffic.

The material effects of this legalized confinement have been profound and pervasive. From women who do roadside food marketing to cinema owners, locals have had to live through an ‘economy in quarantine,’ a situation in which the routine capitalist runnings have become too dangerous to permit. Trinibagonians have tolerated the new measures, aware of the fatal alternatives. Yet they have not been sentimental about the grave economic costs of the new Corona regime.

Take, for example, the predicament of those laboring in the local music industry, which is dominated by the soca genre. Like athletes, intellectuals and strivers in general, performers of Trinbagonian music have had to leave home to profit from their talent. Each year, soon after the famous annual Carnival that pulses the production of soca music, singers and musicians head north to ply their trade, to “eat ah food”, as locals might put it. For them, a successful tour in the US, Canada and England can be the difference between remaining in the industry or choosing another line of work. By the end of February this year, there were already advertisements for singers with the biggest hits to perform in parties and concerts in Brooklyn. The arrival of Covid soon dissolved these events.

Yet the story of “quarantine culture” in Trinbago is not simply one of misfortune and loss. Creative talents compelled to stay at home have awakened to the nightmarish history of the Corona moment and have taken up their call to reflect on it. I count myself lucky enough to know a few of these local laborers, a trio specifically. In the last few months, Azriel Bahadoor, Ryan Chaitram, and Michael Toney have seized upon this period of historic stuckness to undertake a documentary that aims to understand what Trinbagonians have made of life under quarantine. Based on interviews with a range of people (from preteen students to bar owners to musicians), the work-in-progress asks subjects to reflect on how the changes wrought by Covid have transformed their ways of thinking and living and, indeed, of dealing with death. In fact, it was hearing about their interview with singer College Boy Jesse – whose “Happy song” was a big hit – that dramatically clarified for me the unhappy times Corona brought to the arena of culture. (Hear the song here.)

Still, the fact that Bahadoor, Chaitram and Toney are currently making this documentary should remind us that “quarantine culture” amounts to more than a grave challenge. It is also a rich opportunity. The compulsion to stay in place has opened up space for Trinbagonians to appreciate that while much is to be gained from traveling abroad, there is no less to be won from pursuing discovery within, from contemplating inward contents with a new purpose and intensity. Indeed, these quarantined times just might push Caribbean people to appreciate a point made by the great poet Derek Walcott when he received the Nobel Prize. Those who stay in a place, Walcott explained to his Stockholm audience, are its true lovers. Everybody else is a kind of tourist.

Sometimes it takes a dreaded disease to teach the wisdom of poets.

This essay is dedicated to the memory of Tony Hall and Dennis Hall for the serious cultural work that they put in and left us.

Congo ~ Haiti ~ Covid

Terry Rey, Professor and Chair, Department of Religion

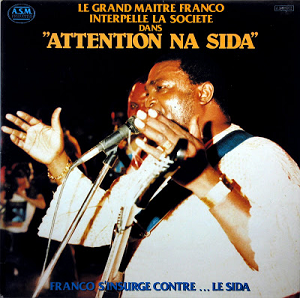

When Hollywood icon Rock Hudson died of AIDS in 1985, it signaled to Americans that the nation and the world were beset by a dreadful pandemic, a disease that was 100% fatal. I was joining the Peace Corps and soon found myself in Zaire, which was othered internationally as “ground zero.” Denial abounded at ground zero, until 1987, when Zaire’s great soukous musician Franco released the hit “Attention na SIDA”, dissolving denial with a single song. Franco, too, would sadly fall prey to AIDS in 1989.

Concerning SIDA (AIDS), my Zairean doctor told me that I should be okay if I “behaved.” It was then unknown whether mosquitoes could transmit the HIV virus, a terrifying uncertainty. He added, though: “You should be more concerned about Ebola. If you find yourself in a village where people are bleeding from every orifice and dropping dead, run away.”

Three years in Central Africa and multiple bouts of malaria and amoebic dysentery later, I moved on in life and married a Haitian woman I had met in Germany. She had been kicked out of her house while a student at Georgetown because her roommates worried that she was afflicted – by virtue of her race, ethnicity, and culture. America blamed Haiti for SIDA.

My wife and I moved to Haiti for six years and now I am in Philadelphia teaching a new course on the Zombie Apocalypse – great timing, I know! – and voting with these figures in mind: That the COVID-19 infection rate in the USA is 27,000 per million, while in Haiti it is 787 per million and in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) it is 123 per million.

Let us fight COVID, denial, othering, and blame, all to a looped soundtrack of “Attention na SIDA”! Great song, and we need music now more than ever, along with a Clorox-free vaccine.

Germany: The Success of Institutions and Coordination

Richard Deeg, Dean, College of Liberal Arts and Professor, Department of Political Science

Germany is widely seen as a country that has dealt relatively effectively in limiting the spread of covid-19 in the country, as well as treating people who became ill. Germany’s comparative success in managing the first wave in the spring rested on several factors: first, Germany had the advantage of watching the virus become a serious problem in southern Europe before the outbreak started growing at home, thus giving Germans time to prepare. Like the United States, Germany has a federal system of government in which state “governors” have considerable responsibility for healthcare and public health. Unlike the United States, however, German politics was not polarized and the virus was not politicized. In fact, Germany has longstanding institutions for coordinating policy among states and with the federal government. Moreover, in recent years Germany has had a grand coalition government encompassing the two major political parties. Finally, Germany benefitted from a popular leader – Angela Merkel – who successfully coordinated federal and state governments around a science-driven response to the pandemic. On a societal level, Germans are less polarized and have higher trust in government and science than Americans. Thus lockdowns, both national and local, as well as masking requirements, were generally accepted with little contention (until this fall, when even some Germans grew weary of the restrictions on daily life).

Germans’ acceptance of the restrictions was also facilitated by the fact that Germany entered the pandemic with a strong economy. When global lockdowns brought a halt to much economic activity, especially the trade on which Germany relies so heavily, the German government quickly resorted to a wage subsidization policy it employed successfully after the 2008-09 global financial meltdown. In sum, political, economic, and social factors in Germany all worked in favor of a successful response.

All that said, it is essential to situate the German response in the context of the European Union. The pandemic put considerable strain on cooperation and unity among the states in the EU. Italians, for example, felt abandoned by their European partners early in the pandemic, and border closings imposed by most member states halted the free movement of people that has been a cornerstone of the EU for the past two decades. Ultimately, with a strong push from Germany, the EU states agreed in April to a 500-billion euro financial aid package to firms. What this reflects, in my view, is Germany’s recognition that it is slowly but surely becoming the central power of the EU and holding the EU together depends more than ever on its commitment of both money and political will. The EU faces many challenges beyond the pandemic, including rising nationalist populism (which drove the UK out of the EU). A strong and committed Germany will not in itself be enough to keep the EU together and moving forward, but it is indispensable.

India: A Nightmare for Migrant Workers

Sanjoy Chakravorty, Director, Global Studies and Professor, Geography and Urban Studies

On 24 March, 2020, the Government of India announced an immediate lockdown of the country. Within a few hours, all commercial transportation—rickshaws, taxis, busses, trains, planes—stopped running. The initial three week lockdown was later extended by several more weeks in multiple stages. Everyone in the country was stuck wherever they happened to be located.

Within days it became obvious the people most adversely affected by the sudden and drastic lockdown were the migrant workers in the growing urban centers, especially Mumbai, Delhi, and Bangalore. There are dozens of millions of migrant workers in India’s cities; because of deficiencies in the census system, the exact number is unknown. These workers lost their tenuous informal sector jobs; their tenuous informal sector housing became insecure; and, faced with no income (and little savings), combined with strained agricultural supply chains, they were faced with serious levels of food insecurity. The education system for their children collapsed, and their meagre access to health care became even more constrained. There remained no reason for them to stay in the cities they had built with their physical labor.

After a few weeks, this population became restive and millions demanded to go back to their home villages. Since that was impossible, thousands of migrant workers began to journey home by themselves, trying to traverse hundreds of miles on foot or some makeshift conveyance, often with their families, and bundles of their ragged possessions. Hundreds died from road accidents and starvation and dehydration. Sometimes, when they reached their village, they were ostracized as disease carriers from the city. By early May, the central government began arranging for “Shramik” (worker) Special Trains to transport migrant workers home. Initially, it was a mess. Some local governments (like Bangalore) refused to let the workers leave so that their construction industry would not suffer if and when it rebounded. The state government of Bihar—India’s lowest income state and arguably the supplier of the largest numbers of migrant workers—refused to take back many returnees. By June, however, a patchwork repatriation system had evolved and appeared to be functioning.

By mid-November, there were over 8.5 million Covid cases in India and 127,000 deaths, second highest (after the US) on both counts. There is continued puzzlement among experts at the low rates of both infection and death after standardizing by population size; for comparable numbers by country, see the World O Meter Coronavirus webpage. The dreaded food disruptions never happened. But much work and many workers have disappeared from India’s cities and no one knows how or when they will return.

Myanmar (Burma) and COVID 19

Jacob Shell, Associate Professor, Department of Geography and Urban Studies

Like many Southeast Asian countries, Myanmar (alternately called Burma), has experienced strikingly little statistically apparent spread of COVID 19. The contrast is especially notable compared with Myanmar’s much larger neighbor, India. The latter, with a total population of 1.35 billion people, has had (as of November 2020) 8.5 million statistically registered cases of COVID 19 and 127,000 deaths. Myanmar is a country of 54 million people and its reported data is 62,000 cases, 1,400 deaths. Even when we adjust for India’s being far more populous, the difference in both prevalence in virulence is an order of magnitude. It would surely be a mistake to conclude anything from this difference—either that Myanmar is “doing something right”; or, that its numbers are simply wrong, that it lacks the medical reporting infrastructure of India. But Myanmar’s evidently low numbers have meant that, for the most part, people there experience COVID 19, not as the direct virological impact of the pandemic itself, but rather in terms of economic damage, especially in the hotel and tourism sectors.

There is also an important level at which Myanmar, which was economically liberalized to foreign investment less than a full decade ago, retains a kind of “backup” social mode where people not getting the basic material support they need from damaged new economic sectors can return to preexisting village- and family-based support systems and food production. The widespread fear of an invisible enemy, one which, if not killing people at a wide scale, is badly undermining the country’s economic hopes, has translated into certain scapegoating frenzies (of a type not unique to Myanmar). An example is a recent trend in some Yangon media outlets of depicting migrants from the country’s oppressed Rohingya minority group as spreading the disease into the country when they cross from neighboring Thailand or Bangladesh.

It should be reiterated that the phenomenon of strikingly low rates of COVID 19 prevalence and virulence characterizes most of mainland Southeast Asia. Too little about the disease, its etiology, and its vector dynamics are understood to say for sure what to make of this phenomenon. A combination of outdoor lifestyle, a slowed pace of life as a kind of social defense against rapid spread, a lack of stigma around the idea of wearing masks, or even the regular presence of bats in Southeast Asian cities, may somehow account for the region’s experience.

Palestine: Radio al-Hara – Can’t Quarantine the Airwaves

Alexa Firat, Assistant Professor, Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Languages and Studies

The average Palestinian living in the Occupied Territories of the West Bank and Gaza was already quite familiar with restrictions on movement before the coronavirus pandemic lockdown: checkpoints to move from one area to another; curfews; military raids, and the like. At the same time, like many people around the world, they had also grown networks that defied boundaries, thanks in large part to the internet. So when quarantine hit in early March, like many of us, Palestinians turned to their computers and cyber networks for distraction from the mundanity. From here developed Radio al-Hara, (literally, neighborhood radio), an internet radio station founded by siblings Youssef and Elias Anastas (in Bethlehem), and Yazan Khalili (in Ramallah), and soon to include Muthanna Hussein, who designs their exquisite visual presence from Amman.

This is not Radio Palestine, as Elias remarks, but rather a local enterprise (hara) with global reach,– it’s just that the local is in Palestine. Music is the main material, but there is also programming dedicated to oral folklore, storytelling, and the “ramblings” of a local chef on food. The beats are based on DJ collections, local and international, so there’s no telling the path of the listening journey (dabke, afrobeats, Bossa nova jazz, and more). Part of a larger platform called Ya Makan, which hosts a number of other internet radio stations (Beirut, Tunisia, Syria, Berlin), the initiative is all about making connections, especially in times of crisis, as this pandemic has made acutely clear. In that spirit, Radio al-Hara hosted a three day “anti-colonial, anti-racist worldwide protest,” against Israeli annexation plans in the Jericho region, Fil-mishmish, equivalent in meaning to “when pigs fly.” It brought together musical voices both Arab and non-Arab in an act of solidarity highlighting the local (hara) struggle in Palestine, but also those across the globe.

The Anastas brothers hope quarantine won’t define Radio al-Hara’s boundaries. They are interested in sound, and as we eventually reconnect outside of our homes, they hope the vibrations of Radio al-Hara will move and adapt with us to echo our changing rhythms.

Much of the details I learned about Radio Hara comes from a few articles written about it in the digital podium Scene Arabia. As well, one can follow Radio al-Hara programming on Instagram and stream it at radioalhara.online.

Peru: Covid, Neoliberalism, Chaos, and Hope

Mónica Ricketts, Associate Professor, Department of History

On March 16th, with only 28 confirmed COVID cases, Peru went into complete national lockdown. The president, Martín Vizcarra, had gathered a group of experts who advised him not to take any risks. If left unchecked and cases proliferated, Peru’s precarious health care infrastructure could collapse in hours. A country of 31 million people, whose GDP had grown at a median of 5% annually in the years 2002-2013, reaching the astonishing rates of 7, 8, and 9% in 2006-8, barely had 100 intensive care units with ventilators, the majority of which were in the capital, Lima. The plan was to radically curtail the spread of the disease and gain enough time to build minimal infrastructure. The measures were well received among middle and upper-class Peruvians, who felt safer under draconian rule. Yet these sectors constitute only a minority. Despite sustained macroeconomic growth, Peru’s poverty rates remain high: 44% of its rural population and 15% of its urban population were considered poor in 2017 and an informal economy prevails (7 out 10 Peruvians do not earn a regular salary). Hence, the government’s plan soon began to crack. While health services did somewhat improve and could deliver while the country was in lockdown, the promised subsidy for those in need was impossible to distribute. Faced with starvation, people defied rules and went out to work; the urban poor began to walk with their families to the highlands and rainforest; caravans of migrants inundated the highways; COVID cases spread like wildfires. In desperation, the government left experts behind and entered into a spiral of marches and countermarches. By August, Peru had become one the countries with the largest numbers of COVID cases and the highest mortality rates. In the midst of this tragedy and rapid economy decline, the government chose to keep the quarantine, open businesses, and get the mining and export sectors working again. Neoliberalism prevailed. These policies are by now so dominant that very few have questioned the fact that kids and the elderly weren’t allowed to leave their houses for more than 30 minutes a day for seven months straight (older adults could only go to the bank and market); too few have cared about the lack of a plan to open schools and to efficiently distribute aid among a growing underserved population. For too long, Peruvians have been left on their own to figure out how to survive. They knew that despite macroeconomic growth a welfare state was well beyond their reach. Many wondered for how much longer would people take this cruel abandonment that had brought along injustice, weak institutions, and a rampant corruption that destroyed political parties.

As it often happens, change came suddenly and unexpectedly, on Monday November 9th, when people, young people in particular, took discontent to the streets. That day congress impeached the president alleging his “moral incapacity” to govern and taking advantage of a loophole in the constitution. Massive national outrage followed, for Peruvians were not willing to accept congress’s coup d’etat five months before an election. This was just too much. All over the country, people masked up, painted signs, and poured into the streets. Protests only worsened when the former head of congress, turned president, presented the country with a blatantly right-wing cabinet, composed of passionate neoliberals who belonged to the white elite. Instead of reconsidering and retreating, this illegitimate government sent troops to repress the protestors. Last night two young kids were killed, 40 went missing, and many more were left injured.

It’s Sunday night now (Nov. 15th) and we have a literal vacuum of power. In the wake of massive insurrection, congress forced the usurper president to resign earlier today. There seem to be three options in this headless condition: President Vizcarra might return next week if the Constitutional Tribunal declares the impeachment null. Despite everything he is still popular, as his decision to close congress and call for new parliamentary elections last year gained him wide approval. Alternatively, congress might elect a provisional government for the next five months, but its highly polarized members cannot agree on a candidate yet. Third, a military dictatorship could take over, which would mean complete defeat for a country that has struggled so hard and for so long to live in democracy.

Peru has never been a country for political beginners, but COVID, corruption, and unchecked neoliberalism have left it shattered in way too many pieces. We just don’t seem to have the capacity to bring them all together to find answers, let along solutions. Our only hope lies in the people on the streets; the kids, who despite repression and hunger, have carried peaceful massive protests without a single incident of looting. They want to live in a clean country and are showing us by example. We cannot let them down.