I worked for the Museum of the American Revolution, in Old City Philadelphia, for about 3 years as a museum educator. I was hired in February of 2020 (a great time to start any new job!) and as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, the education department quickly pivoted to online and Zoom programming. The museum has a robust online tour, with excellent 360º pictures of objects and documents. In person, tours are done at quite a quick pace, and I typically emphasized objects over documents, because they are often more exciting in person. (Declaration of Independence excepted- students always love that one). But over Zoom, I had the opportunity to really utilize archival materials and eighteenth-century documents. I could zoom in, highlight text, and really break down what these documents meant. The biggest barrier to eighteenth century documents, printed or manuscript, is the text itself. Younger and middle grade students find it strange and sometimes unapproachable. My strategy was to make this challenge a part of the assignment; I don’t expect students to come in knowing how to read these documents, instead, we figure it out together.

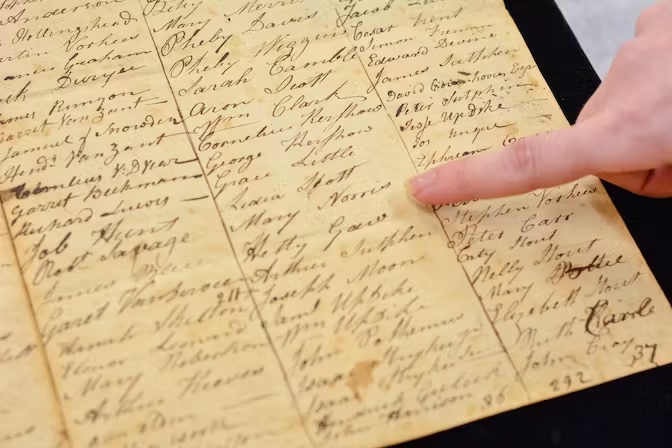

My favorites to examine with students were the nineteenth century New Jersey poll lists, which feature the first female voters in the country. In New Jersey, some women had the right to vote in between 1776 and 1807, provided they owned a certain level of property. More than 150 women voted over the course of those years, and the poll lists, which were on loan from the New Jersey state archives, were on display at the museum for about 6 months and are still available online.

I found teaching with documents exciting. Even young students (I worked mostly with middle grade students at the museum, but my favorite students were the 4th and 5th graders) can engage with archival documents, and it’s exciting for them to see something “real.” I think archival materials works best as a supplement, or as “evidence” for something they learn from a textbook. These strategies introduce students to primary sources early, and I also think they help students learn valuable media literacy skills, useful skills beyond the classroom.

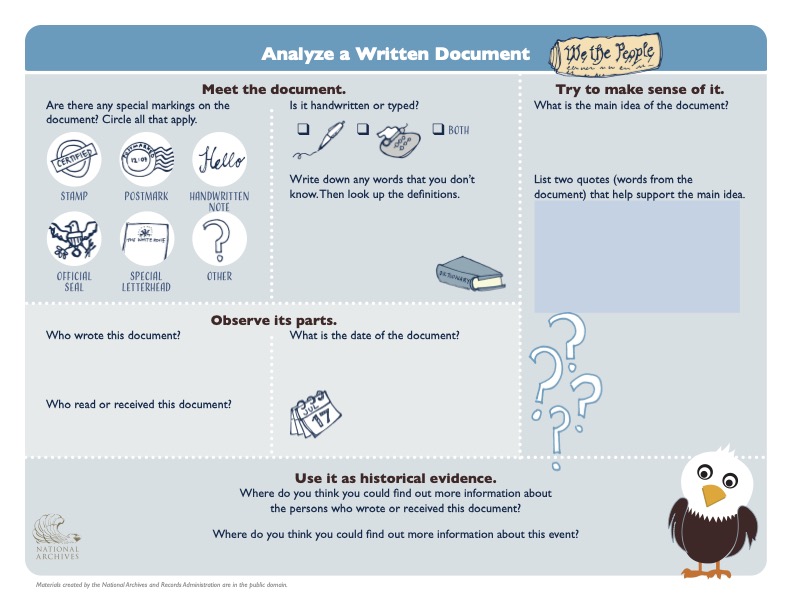

I looked at some of the lesson plans available on the National Archives website, and I focused on the worksheets available for teachers. There are two categories, one for younger students and one for intermediate or secondary students. There are actually not significant differences between the two worksheets, except that the one aimed at younger students has images/fun cartoons on it. In my mind, this is a missed opportunity to ask older students deeper questions (I found that if you talk down to them, you lose them). It is good to see these resources available for free through the National Archives website. Developing these resources is one arm of this effort, but making sure that teachers know about them is another. In this respect, connecting with other institutions in the field with larger outreach footprints may prove useful. For university archives, like Temple, this population is quite close at hand. For private or smaller archives, they may want to connect with museums or libraries.

These strategies, of course, are dependent on digitization! There are significant barriers and difficulties inherent in digitization, and that availability falls unevenly across the industry. Archives should think about ways to engage with students beyond digital documents in classrooms. Could students visit on field trips? Could documents in good condition travel to classrooms? Could students collect material from their own lives to understand the importance of archival materials? Although the industry is in a very different place now than when Timothy Ericson wrote his article, “Preoccupied with our own Gardens,” I think many of his insights are still relevant. Archives have much to offer the population, from students to genealogists to adults, and the industry should think broadly about how and where to engage these populations.