My research on American Girl dolls, and the Kaya doll specifically, has been both an exciting and reflective process.

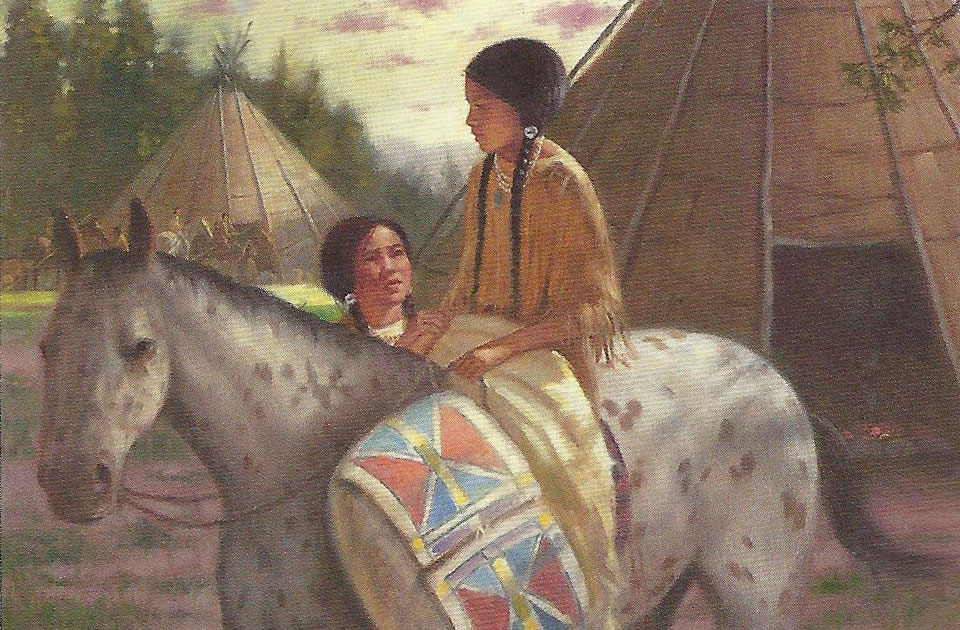

Kaya is situated at a crossroad of scholarship on dolls (American girls specifically, but scholarship on dolls more generally has been useful as well) and Native American representation. Dolls have long been viewed as an object through which multiple layers of femininity, appropriate gender roles, and socialization more generally are enacted. For the American Girl company, this is also a place to leverage stories of historical girlhood to sell dolls and outfits. The sometimes competing and sometimes complementary goals of consumerism and education define the American Girl company. Positioning themselves as an alternative to Barbie, the stories emphasize often contrary stories about rebelling in individual ways against traditional feminine gender roles while ultimately returning to a style of play in which feminine values like dress-up, nurturing, and hair care are big themes. Kaya’s collection stands apart from many of the themes which dominate other collections. Most dolls have various dresses and tie-in accessories, and many focus on the bedroom or kitchen. Kaya’s collection has only one dress directly related to her stories (her “trading” outfit), and the others are recreations of modern-day jingle dresses, which reflect current Native American fashions.

I have also been wondering about my own role here. Kaya was the first doll I received; in our interview, my mother told me she worried about why I chose that doll. She was concerned that I did not choose a doll that looked like me- did I have a self-esteem problem? Though she came to value Kaya’s educational and aesthetic contribution to my life, I think it is worth prodding at whether Kaya was seen as a “worthy” purchase for that amount of money. I was the only one of my friends who had Kaya, and my mother speculated that she did not sell well in comparison to other dolls with larger collections and prettier clothes.

Kaya also stands apart from previous depictions of Native Americans in toys. There is a long history of “playing Indian” in white American childhood games, and Barbie perpetuated the negative and limited depictions of Native Americans throughout the 1990s. Kaya’s release in 2002, then, marks a breaks with the vague and generalized “Indian” depiction with a specific story unconnected with white European settlement. Despite the shortcomings in her stories (the presupposition that Native Americans have an intrinsic and essential connection with nature, for one) Kaya is still a vastly different product and play experience than other toys which depict Native Americans.

Wrapped up in this research is my own experience playing with Kaya as a child. My oral history interview with my mother was really productive, and mirrored a methodology used in the source which has been most useful thus far, Emilie Zaslow’s Playing with the American Doll: A Cultural Analysis of the American Girl Collection. Zaslow interviewed mothers and daughters about what they found attractive about the company, what they liked and disliked about the dolls. Their answers on the educational value of the dolls are strikingly similar to my own mother’s answers to similar questions, but the part of the oral history I think is perhaps even more useful was my mother’s class analysis. She was uncomfortable with the American Girl price point but felt that as a well-made educational doll it was an investment purchase. American Girl dolls are still essentially an upper middle class to upper class signifier (barring programs like libraries lending out dolls), and she saw the doll as like a membership to a country club.

Zaslow also has a chapter about non-black ethnic American Girl dolls like Kaya and Josefina, who she argues exist in stories largely disconnected from discrimination. Those stories contrast with black dolls like Addy and Melody, whose stories are defined by oppression.

The one piece I feel I am still missing are Nez Perce voices. The specific names of Kaya’s historical and cultural advisory board are not public, and my attempts to find the identities of individuals are thus far unsuccessful. Is Kaya’s story for them? Do they feel connected with it? These questions, which seem to be unanswered by current scholarship, are important to understanding Kaya’s impact. Is she truly a break from previous Native American representation in toys and dolls? Or is she another example of white American children “playing Indian”?