In previous weeks, we have explored the foundations of oral history from several practical angles, including the history of oral history and the nature of shared authority. Then, in order to bring these definitions to life and see oral history put into practice, we examined concrete examples of labor oral history interviews. Reading Swing Shift allowed us to experience the analysis-driven final intended product of an interview-gathering process. With foundations laid and our feet now firmly planted, this week we look up to the sky, so to speak, by focusing on Theory. In Oral History Theory, our assigned reading for this week, Lynn Abrams surveys the range of different theoretical frameworks with which oral history may be more thoughtfully and effectively conducted. This class is officially named “The Theory and Practice of Oral History,” and one might assume at first glance that these two facets exist in isolation, but Abrams argues that “practice and analysis cannot be separated” when conducting oral history, and that “the process of interviewing cannot be disaggregated from the outcome.”

Theoretical Promiscuity, to borrow from Abrams’s terminology, describes a key theme throughout her book. According to Abrams, oral history is “a discipline with undisciplined tendencies, continually drawing upon other disciplinary approaches, and in flux as it defines accept able practices and modes of theorising. It is at the same time profoundly interdisciplinary, a promiscuous practice that, jackdaw-like, picks up the shiny, attractive theories which have originated elsewhere and applies them to its own field of study.”[1] In other words, the mutability of oral history-making pushes scholars to analyze oral sources in multilayered ways using theoretical frameworks derived from linguistic (orality), literary (narrative), psychiatric (memory), neurological (trauma), and other non-historical disciplines of study.

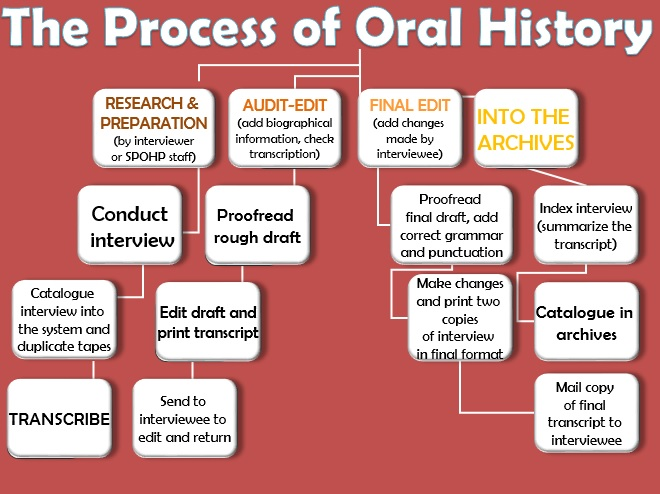

I hadn’t realized how much oral history, as both process and product, is subject to continuous change. Narrators first translate their stories and experiences into suitable responses to the interviewer’s questions, and this process is greatly shaped by the quality of an interviewer’s questions. The interviewer constructs their own understanding of what is shared, ideally striking a balance between engaging with broader research questions while giving narrators enough space to tell their stories. The resulting conversation is then winnowed through a transcription process laden with its own pitfalls (is it ethical to render dialects into more standardized forms speech for the sake of easier comprehension by a wider audience?), after which the narrator has the opportunity to redact any of their own words. Finally, the oral historian breaks apart this already much-transformed product, sprinkling fragments of many interviews into a scholarly book or article, holding them up against available archival and written sources, and binding everything together with analysis.

And it doesn’t stop there. Step outside of the process of oral history-making, and we can see how oral history itself, the theories and methods used to create it, also evolves over time. The study of trauma within oral history, for example, its effects on narrators and interviewers alike, is a newly emerging field within oral history which will help inform how best to approach projects involving survivors of war, genocide, natural disasters, or other traumatizing experiences. In the first edition of Oral History Theory (2010), Abrams plants the seeds for the second edition by examining (in the chapters about Memory and Narrative) how trauma can leave holes in a narrator’s memory and prevent narrators from arranging memory into cohesive narratives. The second edition (2018), however, features a new chapter devoted entirely to trauma, the ethics of working with traumatized narrators, and a painstakingly navigated distinction between viewing oral history as therapeutic for traumatized narrators (ill-advised) versus acknowledging that oral history is not inherently therapeutic (despite whatever Freud might say), but catharsis can sometimes happen as an unintended byproduct. The evolution of Abrams’s own book reflects the evolution of crisis oral history into a sub-field of oral history in its own right.

[1] Lynn Abrams, Oral History Theory, 2nd ed. (Routledge, 2018), 32.