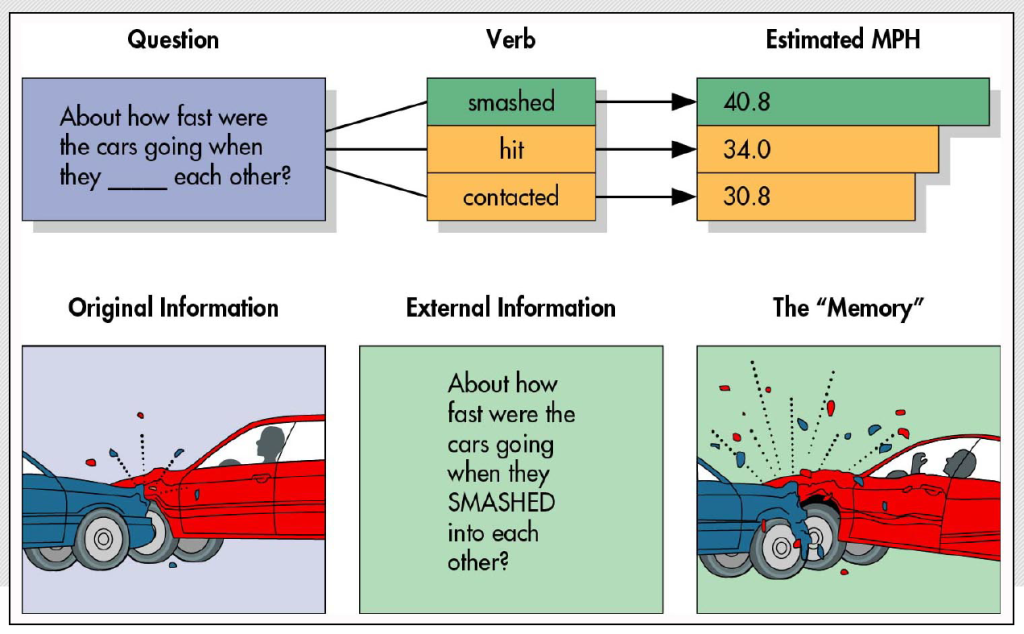

When I teach my students about the importance of deliberate word choice in questioning witnesses, I often begin with the Loftus and Palmer (1974) experiment on reconstructive memory. Participants watched car-crash videos and were asked to estimate the vehicles’ speed. Those who were asked how fast the cars were going when they smashed into each other reported an average of 40.8 mph, compared to 34.0 mph for hit and 30.8 mph for contacted. More tellingly, the smashed group was more than twice as likely to remember broken glass on the road—glass that never existed. A single verb altered not only the witness’s perception of speed but their entire recollection of reality.

I use that example to illustrate how easily language can shape memory, but reading Lynn Abrams’ Oral History Theory gave me a new vocabulary for why this happens. Abrams describes memory as reconstructive rather than reproductive: each act of remembering is a negotiation between the narrator’s inner world and the cues provided by the listener. In both oral history and the courtroom, the listener—the interviewer, the lawyer, the judge—plays an active, constitutive role in the story that emerges. Abrams’ insistence that “the interview is a shared performance” could just as easily appear in a trial-advocacy manual.

What struck me most is how Abrams situates the interviewer within the moral and emotional texture of the exchange. She writes about intersubjectivity—the mutual influence that shapes both question and answer. Lawyers, too, must attend to that dynamic, especially in trauma-informed or culturally competent practice. I’ve seen witnesses from high power-distance or collectivist cultures avoid direct answers, not out of evasion but out of respect. I’ve seen survivors of violence tell their stories in fragments because linearity is impossible after trauma. Abrams’ framework reminds me that listening ethically means recognizing the cultural and emotional scaffolding around every utterance.

Her treatment of performance also resonated deeply. Every interview, she argues, is a performance staged within social expectations—of gender, class, race, and power. In court, credibility is similarly performative. When judges instruct juries on how to evaluate a witness, they list factors like the depth of detail, the witness’s demeanor, any motive to fabricate, and the “ring of truth.” But all of those criteria are interpretive; they rely on cultural assumptions about what sincerity looks and sounds like. Andy Taslitz’s work, Rape and the Culture of the Courtroom, describes how Black women often feel compelled to modulate tone, diction, or posture to appear credible to predominantly white juries. Abrams’ notion that narrators seek composure—to reconcile their private selves with public expectations—maps precisely onto that struggle.

I also found myself reflecting on Abrams’ warnings about the emotional cost of bearing witness. She writes of vicarious trauma and the ethical duty to acknowledge the interviewer’s own vulnerability. Lawyers rarely speak in those terms, but we experience it constantly: listening to clients recount assault, loss, or systemic injustice. The professional demand to remain detached can mask the fact that listening is labor. Abrams reframes that labor as a moral practice—one that requires reflexivity, empathy, and boundaries. Those are precisely the skills I hope my students carry into their own encounters with clients and witnesses.

Perhaps most powerfully, Abrams dismantles the myth of objectivity that still haunts both historians and lawyers. She argues that oral history is not about retrieving pure facts but about constructing meaning through relationship. The same could be said of advocacy. Before a witness ever takes the stand, an attorney must evaluate credibility through an interpretive lens: weighing corroboration, motive, demeanor, and narrative coherence. Then the fact-finder repeats that interpretive act in deliberation. What Abrams calls the “co-creation of knowledge” happens in court every day; it’s just that lawyers rarely admit it.

Reading Oral History Theory made me realize that law and oral history share a fundamental faith in the power of story—not as decoration to facts, but as the structure through which facts gain significance. Abrams’ insistence on listening, empathy, and self-awareness turns what could have been a technical manual into an ethical guidebook. It teaches that truth is never a fixed object waiting to be extracted, but a collaborative act of meaning-making between speaker and listener. For me, that lesson reframes what it means to be an advocate. To question a witness is not simply to test memory; it is to participate in the fragile, creative process of constructing truth. Abrams reminds me that every word—whether hit, smashed, or contacted—has the power to alter the landscape of memory itself. As both historians and lawyers, we are custodians of that power, and our task is not only to persuade but to listen with rigor, humility, and care.