Prefatory Note

*Although Caroline West does not explicitly describe Wrong Women: Selling Sex in Monto, Dublin’s Forgotten Red Light District as an oral history, the back cover copy states that the book “draws on oral history” to tell the stories of women who lived and worked in Dublin’s Monto district. My critique, therefore, proceeds from the perspective of an oral history student evaluating the text through the methodological standards of the field. For the purposes of our course, Wrong Women would not qualify as an oral history text, because its sources, structure, and evidence do not align with the defining principles of oral history practice. I felt the need to add this note because what follows is an analysis of what Wrong Women is not, but not a critique of what West ever claimed it to be.

Caroline West’s Wrong Women: Selling Sex in Monto, Dublin’s Forgotten Red Light District (2025) announces itself as an act of recovery. “Beyond the simple binary of exploitation and empowerment, this book is a study into the history of the unrecognized, the voice that other people would prefer not to hear, and the spectrum of violence against women, particularly marginalized women” (West, 2025, p. 6). Yet from its opening pages, the book exposes a central contradiction: it declares that it “draws” on oral history, but its actual reference to oral testimony is limited if what’s included can be deemed oral history at all. The women who populate West’s pages—sex workers, former laundry inmates, street children, madams and social reformers—died long before recording technology, and their “words” survive only as hearsay relayed through their descendants, barely any of whom know of the Monto at its peak – from 1860-1925. What emerges, then, is not oral history in the methodological sense taught by Ritchie (2014), Sommer and Quinlan (2024), or Perkiss (2022), but rather a hybrid of archival research, social commentary, and empathetic speculation.

Monto was once reputed to be the largest red-light district in Europe. West aims to restore its women to historical visibility. “The women of…Monto have shaped the course of history. But we have learned from them without acknowledging them” (West, 2025, p. 265). Her ambition—to retrieve agency and voice from stigma—is both feminist and urgent. West (2025) acknowledges: “While we can’t directly interview the women and girls of Monto, this book strives to promote their voices as much as possible and support them with the voices of their descendants” (p. 7). This acknowledgement hints at the methodological slippage that follows.

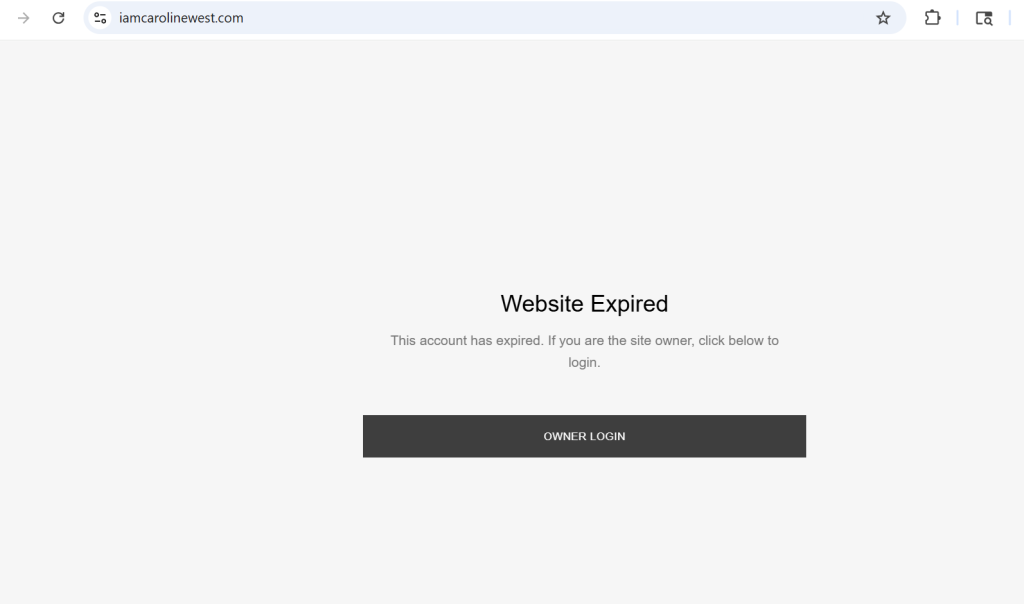

One of the most striking weaknesses of Wrong Women is its sourcing. As a student of oral history, I have learned that transparency about one’s sources—who was interviewed, when, how, and under what conditions—is an ethical cornerstone of the field. Yet Caroline West’s book provides no way for the reader to verify or trace the origins of her material. There are no citations, reference notes, or interview transcripts of any kind. Instead, West includes just a page and a quarter titled “Further Reading,” listing twenty-one general works. At the bottom of that page she writes, “For a full bibliography and reference list, please visit www.iamcarolinewest.com.” When I navigated to that site, however, I found only a dead link: “Website Expired. This account has expired. If you are the site owner, click below to login.” For a book that claims to draw on oral interviews, this absence of verifiable documentation is troubling. It prevents readers and researchers from checking context, assessing reliability, or even confirming that the interviews occurred in the form implied.

West does identify several individuals as sources, but their relationship to the Monto era (roughly 1860–1925) is tenuous at best. She cites “a great-great-granddaughter and a great-granddaughter of madam Annie Meehan…who grew up hearing whispers and snippets about what her grant-granny had been up to” (West, 2025, p. 7). Another informant is “a great-grandson to madam and convicted murderer Margaret Carroll” (West, 2025, p. 7). Martin Coffey is the author of a book called What’s Your Name Again? “He has sifted through his family history to discover how their connections to Monto have shaped his family since Margaret was convicted” (West, 2025, p. 7). A third source, folklorist Terry Fagan, recorded stories from elderly Monto residents decades after the district’s closure; West writes that “through his interviews, we can hear a visceral account of life in the tenements” (West, 2025, p. 8). She also mentions “women working in the sex trade today,” interviewed at a 2023 banner-making event for the International Day to End Violence Against Sex Workers, as well as “thoughts from journalist Sarah McInerney,” who covers contemporary violence against women in sex work (West, 2025, p.8).

Finally, West (2025) summarizes her method this way: “The stories from my interviews [with the aforementioned people] are woven through medical records, memories of local residents, official documents, academic theories, folklore, scraps of words and sentences, and the experiences of those in similar situations at the same time as Monto’s existence” (p. 10). Taken together, these statements show that none of West’s informants possess firsthand memory of Monto itself. What we have instead is a chain of mediated recollections—descendants repeating “whispers and snippets,” contemporary sex workers reflecting on parallels, and a folklorist recalling what others once told him. Each of these layers introduces distance, interpretation, and hearsay. From an oral-history perspective, that matters: as Sommer and Quinlan (2024) emphasize, oral history depends not just on words spoken, but on the documented interaction between interviewer and narrator—the conditions under which memory is recorded, preserved, and contextualized. Without transcripts, dates, or audio files, West’s “voices” remain untraceable.

Throughout Wrong Women, West employs the rhetoric of orality without the practice of oral history. Chapter 19 mourns all that we do not know about the women of Monto:

We don’t know about the woman’s inner lives, their sense of self or self sense of humor. Who were they beyond the label of ‘poor unfortunate’?… How much power and choice they had in their day-to-day lives? How did they understand sexual violence, power dynamics, consent, pleasure, pregnancy and contraception?…How did they think about their experiences [in Monto]? We don’t have…enough information on how the women of Monto responded to [the] stigma [that accompanied being a sex worker] (West, 2025, p. 281).

This passage epitomizes the book’s paradox. The women’s experiences, then, are speculated, not recorded. If oral history is defined by the process of interviewing and recording the memories of living individuals who consent to share their experience within a relationship of trust, then to imagine what someone might have experienced or might have reacted is a literary gesture, not a methodological one. West’s empathy is palpable, but her practice collapses the distinction between reconstructing and hearing.

To her credit, West acknowledges this gap. There are no or very few records and actual accounts from Monto, so West repeatedly uses examples from brothels in New Orleans, San Francisco, Paris, London, and Australia for comparison and to extrapolate what conditions in Monto may have been. West quotes a recollection reflection from a man about how his grandmother

…could have felt living in these conditions after moving to Dublin to reunite with her mother after growing up separately from her in Tipperary. ‘The tenement houses in the area where her mother lived out her life must have been very strange indeed for this young country woman, with the smell of boiled cabbage, bodies washed and unwashed, hallways marked with years of blood, sweat and tears, stairways drenched and stained from all sorts of human waste that was carried out in buckets to the one and only toilet in the backyard. Did she perhaps, at any time, long for the fresh clean air of Thomastown in county Tipperari?’ (West, 2025, p. 72).

Such passages reveal the book’s distance from oral history. Oral history does not imagine what someone must have felt; it records what someone remembers feeling. West generates intimacy through empathetic conjecture, not through a reciprocal exchange that defines oral history.

West yearns for evidence of a “guidebook” (a/k/a a “blue book”) for Monto’s red-light district (though she has found no such primary source yet). “While these guides proliferated across the British Empire, we must ask – was there a blue book for Monto?” The author cites to several print and stationary shops in the vicinity of Monto on Sackville St. She then speculates “if [the printers] could make money on the side it was surely an opportunity not to be ignored, and they may also have been the ones to print the business cards that the madams gave to sailors. It is not a stretch to think the madams saw the value of this form of communication [newspapers]” (West, 2025, p.87, emphasis added).

Chapter 6 continues with this wishful thinking: “Perhaps one day a scrap of paper will be unearthed in an old dockyard halfway across the world with the names of Monto’s inhabitants and their specialties splashed across it” (West, 2025, p. 88). There was evidence that a printer named Bartholomew had been invited to a masquerade ball by “the queen of the red-light scene in Dublin.” Based on this invitation and no other cited evidence, West (2025) writes “Bartholomew was clearly comfortable with the sex trade and happy to do favors for his favorite Madame” (p. 87). Other powerful people in the printing business and distribution business had been invited to that same masquerade ball, from which West speculates: “these party guests show a connection between people with power in the printing and distribution businesses and those in the sex trade, making a blue book of some kind a real possibility” (p. 88). Finally, citing no one, she concludes: “most likely, if such books did exist, they perished on their onward journeys or were deliberately destroyed by vigilantes or reformers” (West, 2025, p. 89).

Just because Wrong Women may not qualify as an oral history, I don’t mean to detract from the diligence of West’s use of archival fragments. She draws on the Irish census data from 1861-1911, the Irish Times, the Legion of Mary ledgers, and court records. Her archival skill is impressive, yet the “voices” that West brings the read are actually textual inferences, rather than records (and certainly not recordings). To paraphrase Ritchie (2014), a historian’s interpretation of a written document cannot substitute for the narrator’s own telling. West’s method collapses that distinction, treating what texts that do exist as equivalent to oral presence. The result is evocative prose but unstable epistemology.

Another reason Wrong Women cannot be considered an oral history is because West (2025) strives to “promote their voices [of the women and girls of Monto]” (p. 7). The intention is admirable, but the phrase reveals an ethical pitfall. To “promote” implies that the historian possesses the authority to bestow voice—a gesture oral historians have worked to undo. For Ritchie (2014), oral history is not necessarily the historian advocating for others but listening with them. West’s method reverses that relation: she becomes the narrator of reconstructed memory. Perkiss’s 2022 Hurricane Sandy on New Jersey’s Forgotten Shore offers a counterexample. Perkiss builds her narrative around recorded interviews, foregrounding the interview process itself—the awkward pauses, the contradictions, the emotions that mark trauma in real time. Through no “fault” of West’s, a narrative of that sort is not possible for the women of Monto. West’s would-be narrators are long-since deceased; thus, her interventions cannot be checked against lived memory or consent. The result is a valiant effort to restore voice that simultaneously replaces it.

Why, then, does the Wrong Women claim to draw upon oral history? The cynic in me (perhaps still under the influence of Abby Perkiss’s disillusionment) thinks it’s partly marketing. “Oral history” now connotes intimacy and authenticity, qualities that publishers value in popular nonfiction. West herself may genuinely see her empathetic reconstructions as a kind of surrogate orality—a way of “listening across time.” Yet Ritchie (2014) would warn us not to call a monologue an oral history; doing so, erases the dialogic foundation on which the field of oral history is built. The issue is not pedantry but ethics: when a historian adopts the label of oral history, readers may mistake well-researched hypotheses for testimony.

**From here to the next set of asterisks is more of a book review and not so much a critique of West’s oral history (or lack thereof). You can skip to the conclusion if you only want my take on why this wasn’t an oral history.

Wrong Women, however, in its own right, still contributes meaningfully to feminist historiography. West dismantles the moral narratives that cast Monto’s women as either victims or sinners. Chapter 1 highlights the economic structures that made sex work a survival strategy. Chapter 11 situates Monto’s Westmoreland Locke hospital within the continuum of coercive societal control of women (and not just the “wrong women”). This chapter explores how syphilis was feminized and how women working as prostitutes were blamed for being transmitters, but not the men who infected them. Though the “Lock” in Monto was not subject to Ireland’s Contagious Diseases Act (unfortunately, West never tells us why), “shaming” the “unfortunates” who sought treatment there abounded:

To compound the harm caused by being targeted by police and detained, the women were then accused of enjoying the examination so much that they had become addicted to the speculum, reduced to being labeled as ‘uterine hypochondriacs’ who craved the exam, and this belief was spread in the pages of influential medical journals (West, 2025, p. 154).

(A discerning reader would have appreciated a citation to or quote from one of those influential medical journals, but alas….)

West also exposes the patriarchal logic that underpinned both the penal and medical systems of her period, showing how women’s suffering was reframed as benevolence. When authorities deemed the institutionalization or incapacitation of women selling sex as a “humane act being done to her” (West, 2025, p. 150), West makes clear that such interventions were not protective but punitive, rooted in a moral hierarchy that pathologized female sexuality. Chapter 14, “Policing the Body,” feels all too familiar in light of modern patterns of sexual violence and victim-blaming. West quotes the Dublin Metropolitan Police’s medical officers, who claimed that when policemen contracted venereal disease, it was not their fault: they were “innocent rural young men who were not used to the vices of a big city, and finding themselves surrounded on their beats with vice and infamy, under many attractive forms, they were probably unable to restrain themselves from the influences brought to bear upon them” (West, 2025, p. 189). The rationalization—that men’s transgressions are the inevitable result of women’s temptation—echoes disturbingly in contemporary defenses of sexual assault by privileged young men, such as Brock Turner, whose crimes were reframed as youthful lapses rather than acts of violence. West’s historical material thus reveals the deep continuity of patriarchal narratives that excuse men and criminalize or medicalize women’s bodies.

Chapter 15 discusses the violence experienced by women in the sex trade – both in Monto and in modern society – and how the media alternates between voyeurism and moral panic. This reveals the patriarchal surveillance shaping Ireland’s modern identity. In these sections, West’s voice is critical rather than speculative, and the book’s historical argument is strongest. “The path forward for ethical reporting lies in understanding how the stereotype of the wrong woman has survived since Monto and is still played out today across the pages and views of modern media” (West, 2025, p. 217).

In its final chapters, Wrong Women moves from exposing systemic injustice to honoring the resilience and mutual care of the women of Monto. Chapter 17, “Disrupters,” celebrates the informal networks of dignity, protection, and resistance that these women built for one another. West (2025) argues that reformers such as Frank Duff “may have received the accolades for being the one to end Monto, but he did so by standing on the shoulders of women” (p. 235). She urges readers to “reflect on the loss of knowledge of the actions of those we will never know, such as the efforts from those in the trade themselves and working-class women” (West, 2025, p. 235). For me, this chapter feels like the emotional heart of the book: it restores a sense of agency to women who have otherwise appeared in history as victims or statistics.

West includes a particularly affecting oral recollection preserved by folklorist Terry Fagan. A man recalls that “when my mother’s granny died in 1917, the priest refused to come and give her last rites… someone on my father’s side made a cross to go over that woman’s bed.… When she died it was loaned out to other families who had prostitutes who had a priest that wouldn’t come to.… I loaned it to Terry Fagan’s Museum, and I gave him the story” (West, 2025, p. 240). This story of the handmade “Monto cross,” passed among families denied priestly blessing, becomes a powerful emblem of community care — women and families creating their own rituals of dignity when the Church refused them any.

Throughout the chapter, West provides examples of agency and rebellion: women choosing prison over the laundries because “they knew they would never get out,” refusing the uniform of the workhouse, changing their names to evade authorities, renaming the brothel district “the village,” and even smuggling weapons to Irish revolutionaries. She reframes such acts not as criminality but as survival — “an act of survival rather than one of callous abandonment” (West, 2025, p. 250). West also bridges past and present, noting the continuation of solidarity through groups like the Sex Workers Opera, the Red Umbrella Film Festival, and the Ugly Mugs Initiative. These examples position sex workers not as passive subjects of rescue but as active agents of mutual aid and political voice.

There is, however, a bittersweet moment at the chapter’s close, when West describes a confrontation between a priest and a notorious madam during the closure of Monto: “Eventually the priest lost his cool with her and shouted her into submission.… Sadly, we will never know what May said to them or what exactly was so powerful about the priest’s speech that took the wind out of her sails.… Duff, through his lack of note taking, ensured they are lost to history” (West, 2025, p. 261). West’s lament here underscores the archival silences that oral history seeks to fill — and the tragedy of record-keepers (in this case, a male record-keeper) deciding which voices survive.

In Chapter 18, “Ethical Remembrance,” West turns explicitly to the question of how these women should be remembered. “The women of the Lock and Monto have shaped the course of history. But we have learned from them without acknowledging them” (West, 2025, p. 265). She identifies this forgotten activism as “the beginning of organized feminism in Ireland,” (p. 266) linking the women’s lived struggle for bodily autonomy and survival to later campaigns for suffrage and social reform. Her proposed framework of Machnamh — “a compassionate concept [in Irish]… meaning reflection, meditation, thought, and contemplation, allowing for a multitude of narratives to be heard and for remembrance to be thoughtful and ethical” (p. 267) — offers a culturally rooted model of remembering that resonates deeply with oral-history ethics.

West distinguishes between mere memorialization and what she calls “honoring the outcast” (p. 271). West (2025) writes, “The difference is the honoring, as opposed to just creating a physical space. The difference between remembering and memorializing is that in remembering we put them back together again.… We turn them into people. We remember that they are people with lives and they’re not just a massive scrabbling misery” (p. 271). This distinction captures the same ethical impulse that oral historians emphasize: the act of remembrance as re-humanization, not spectacle. West concludes that “ethical remembrance needs to be conscious of not retraumatizing those sharing their stories” (p. 275). This recalls Abrams’s (2016) trauma-informed approach to oral history practice. West concludes with praise for folklorist Terry Fagan’s recorded interviews: “to hear their history, in their own words, accents and tone, is not only a democratic way to learn, but also an ethical one that centers the people themselves” (West, 2025, p. 280).

Together, these final chapters point toward what Wrong Women could have been if its oral sources had been more fully available: a true act of Machnamh, a reflective listening that dignifies the speakers rather than speaking for them. For readers trained in oral history, these chapters are both inspiring and instructive. They remind us that empowerment is not only in retelling the past, but in building the ethical frameworks that ensure every retelling honors the people whose lives make it possible.

**

Wrong Women: Selling Sex in Monto, Dublin’s Forgotten Red Light District is a vivid, compassionate, and rigorously researched account of an overlooked world. Yet it is not an oral history. Its “voices” are reconstructions; its evidence, archival; its empathy, authorial. To label it oral history is to mistake the presence of voice for the practice of listening.

Reading Wrong Women after studying oral-history methodology changed how I interpret historical writing that claims to “promote voice.” Before this course, I might have accepted West’s narrative empathy as oral history by another name. Now I see the difference between writing about silenced people and listening to them. In Ritchie’s 2014 framework, oral history redistributes authority; in Perkiss’s (2022), it preserves the raw texture of experience; in Sommer and Quinlan’s (2024), it documents context as carefully as content. West’s book, though powerful, remains bound by the author’s interpretive voice.

At the same time, Wrong Women demonstrates why scholars and students are drawn to oral-history language even when true interviews are impossible. The hunger for voice—for proximity to lives erased by shame or time—is real. West’s impulse to “hear” these women is not wrong; it is simply not oral history. Her work inhabits what we might call a historiography of empathy: a form that borrows oral history’s moral energy but translates it into imaginative narrative. Recognizing that distinction allows us to appreciate her important research without confusing it for oral method.

West’s book reminds us students of oral history that the discipline’s strength lies not in eloquence but in relationship—between interviewer and narrator, memory and record, consent and interpretation. West succeeds in restoring dignity to Monto’s women, even if that restoration does not take oral history’s collaborative form. In doing so, she leaves us with a valuable paradox: a book that makes us want to listen more carefully, even if the actual voices of Monto’s women may forever be out of reach.

Works Referenced

Abrams, L. (2016). Oral history theory, second edition. Routledge.

Perkiss, A. (2022) Hurricane Sandy: On New Jersey’s forgotten shore. Cornell University Press.

Ritchie, D. A. (2014). Doing oral history. Oxford University Press.

Sommer, B. & Quinlan, M.K. (2024). The oral history manual, fourth edition. Rowman & Littlefield.

West, C. (2025). Wrong women: Selling sex in Monto, Dublin’s forgotten red-light district. Eriu Books.